Beauty Horror: the gore-geous fairy tale micro-genre

The Substance (Coralie Fargeat, 2024) and The Ugly Stepsister (Emilie Blickfeldt, 2025)

Horror moves in fashions, and sometimes something new crawls up from the sticky neural pathways of our subconscious. Often it drips blood – but in the last couple of years we’re seeing something interesting: it’s also dripping lace and spandex.

There’s a little micro-genre emerging that I’m going to call ‘beauty horror’. Will it become a big thing? It’s too early to say. But let’s talk about it here and see what we’ve got.

Where’s the trend right now?

We’re in a transitional moment. The YouTube channel Girl on Film recently put out a video arguing that ‘elevated horror’ – which she defined as – ‘high concept emotionally complex stories grounded by realism in their visual presentation and performance style’ – has passed its heyday. No genre can be the Next Big Thing for ever, and it’s part of the inevitable cycle that you get a few new and exciting films with some real imaginative energy, then some naff imitations that copy the general impression without understanding the creative force behind them, and it all stops looking so shiny and new.

Then something else comes along and looks more shiny. Girl on Film suggests that recently it’s high-class schlock, more camp, colourful and hyper-real than subtle and naturalistic. She doesn’t use the phrase, but ‘elevated gore’ is definitely a factor. She mentions The Substance as a big example, and indeed, it won a bunch of awards and was the word on all lips last year.

Noodling on Shudder (The Substance is on Amazon Prime), I found the perfect film to put in its double-feature. Out this year, The Ugly Stepsister is really a trip: a Norwegian retelling of the Cinderella myth mostly from the viewpoint of, well, the clue’s in the title.

Put these together and I’ve got another proposition:

If elevated horror loved to use folk tales, right now it’s a moment for fairy tales.

What’s the difference?

Well, when I say folk tales, think of The Witch (Robert Eggers, 2015), explicitly calling itself a ‘New England folk tale.’ Think of It Follows (David Robert Mitchell, 2014), an urban legend on the hunt. Think of The Babadook (Jennifer Kent, 2014), a childhood boogeyman with no easy ending. Think of Get Out (Jordan Peele, 2017), making a nightmare out of a culture’s racist shadow. These are stories that wash around our culture when we want to warn about something hard to speak of openly. There’s no happily ever after, just unsettling murmurs that you either learn to live with or you don’t.

Fairy tales don’t so much whisper warnings as they teach morals. There are clear rewards and punishments, rules that you follow or you break, transactions whose terms are clear from the outset.

Robert Eggers’ Witch of the Woods steals a baby without warning and kills it to make a magic potion. There was no way to see it coming. That’s a folk tale.

A fairy-tale creature like Rumpelstiltskin tries to take a baby because that was made explicit in the bargain, and is powerless if the princess can find another way around the rules. Fairy tales are magical, but you can’t say they didn’t warn you.

Let’s talk plots

I went into The Substance unspoiled, but actually I’m not sure the plot is really the point. It’s brilliantly edited with a driving through-line that keeps you going with the force of a glossy ad, but events in it are not going to surprise you. All the surprises are visual.

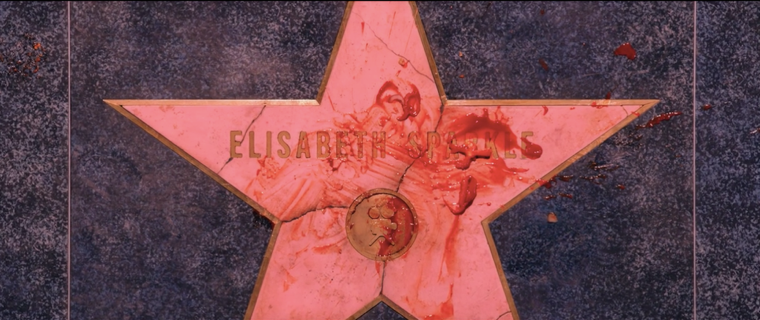

Elizabeth Sparkle (Demi Moore) was an Oscar-winning actress once upon a time. For years after that she had a kind of Jane Fonda aerobics show on TV, and she was an undoubted star – but then the network decides to terminate her for being over fifty.

Everyone in the network who has a say in this decision is also over fifty, generally much older than her and far less well-preserved, but they’re all rich white men and she’s a female performer, and those are different species. Elizabeth’s star is knocked out the sky by a bunch of sleazy old gits.

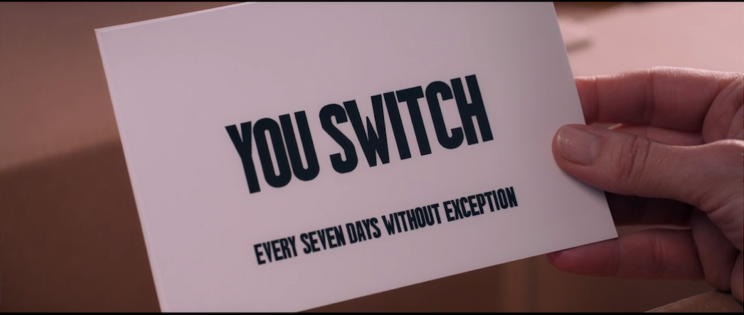

Except an unsettlingly handsome young doctor suggests to her she try ‘the Substance’. The Substance, which runs on injections, produces a double: ‘younger, more beautiful, more perfect’ than you. There are just three rules:

- You activate only once.

- You stabilize every day.

- You switch every seven days without exception.

And remember, the anonymous producers warn you: YOU ARE ONE.

In practice, the ‘you’ that isn’t in use goes into a kind of coma. The new you has to draw bodily fluids from the comatose old you and inject them every day at the exact same time, or her body starts to go into shutdown.

And if she gets greedy and tries to steal extra time before returning life to the old you . . . well, the old you starts to age hard and fast.

The trouble is that these bodies don’t share each others’ memories, or not once they start living separate lives. They’re ‘one’ in the sense that they’re magically linked – but they don’t experience themselves as the same person. Sue, the ‘new’ Elizabeth, auditions for Elizabeth’s old job and becomes a star, but she really doesn’t like having to hand over when the time is up. So soon enough, Elizabeth and Sue are at war for their disputed life, and of course when you fool around with a magical beauty potion, body horror is what you get.

This is a cautionary tale.

Structurally the lesson is familar: don’t take a mysterious deal – or if you do, stick to the terms and don’t get carried away. What happens to Elizabeth-Sue is dramatic enough physically that I won’t post visual spoilers, but you know this story. You’ve heard it before.

It’s Eve, a Garden of Eden’s worth of food before her, eating the one fruit she was told to leave alone.

It’s Cinderella’s coach turning back into a pumpkin if she overstays the chime of midnight.

It’s the Thomspon fairytale motif of the ‘immoderate request punished’ and ‘one should not be too greedy’.

It’s the lady of Llyn y Fan Fach, the fairy bride who promised to stay with her husband unless he hit her three times; he did, so she left. (Thanks to Cheryl Morgan for pointing that one out.)

It’s the Snow Woman of Kwaidan, the storm spirit that freezes a man to death but spares his handsome young apprentice on the condition he never tells anyone about her. Later he marries a mystically beautiful woman and finally confides the tale, only for his wife to reveal that she is that same snow spirit who fell in love with him all those years ago, and now he broke his word, so she’s off.

You know this story. A magical force makes you an irresistible offer – but it comes with a condition, and woe betide you when you break it.

This is fairy tale stuff. If the Brothers Grimm were telling it there might be a good fairy or a rescued animal that could come up with a new set of conditions that would break Elizabeth out of the first ones, but it’s a horror movie, so instead this is what we get.

But that’s not outside the fairy tale. Do you know ‘Diamonds and Toads’? A fairy rewards a polite girl and punishes a rude one; diamonds fall from her lips when the former speaks, toads from the latter.

Elizabeth is in a fairy story all right. Only she’s the sister that doesn’t win.

Mutilation or grotesquery is often what happens to the women who lose in these stories. They dance in red-hot shoes. They’re rolled in barrels of nails.

Or, if they’re Cinderella’s ugly stepsister, well shit.

The Ugly Stepsister

Did you know that in the Grimm’s version of Cinderella, birds pluck out the stepsisters’ eyes?

Those girls got off lightly.

Elvira (Lea Myren) is eighteen and her mother just remarried. She has a younger sister, Alma (Flo Fagerli). Both of them begin the story travelling to live with their new stepfather.

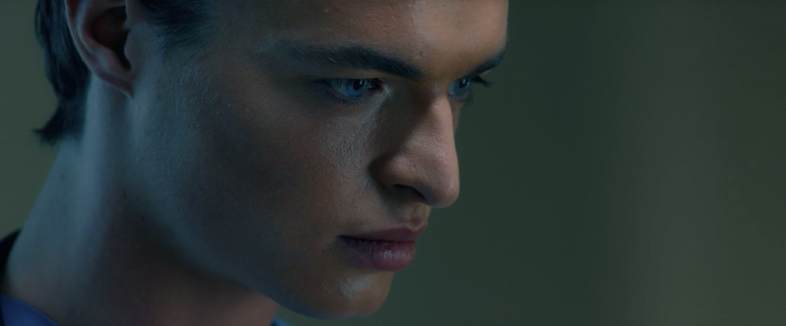

Their stepfather has a daughter too, a girl called Agnes. Agnes looks like this:

Elvira looks like this:

Alma, the ‘ugly stepsister’s younger sister, looks like this. Put a pin in that thought.

Things become awkward right away: Elvira’s stepfather dies and it becomes clear that it was a disastrous marriage of convenience – each married the other for money, neither realising their new spouse was just as broke as they were.

What’s Elvira’s mother to do? Well, as chance would have it the Prince declares a ball: four months from now he wants to meet every noble virgin in the country so he can pick a wife. That might save them all! There’s no love lost between Agnes and her stepmother, so it has to be one of her own daughters. And Alma is too young to be fertile.

They’ve got four months to whip Elvira into marriageable shape.

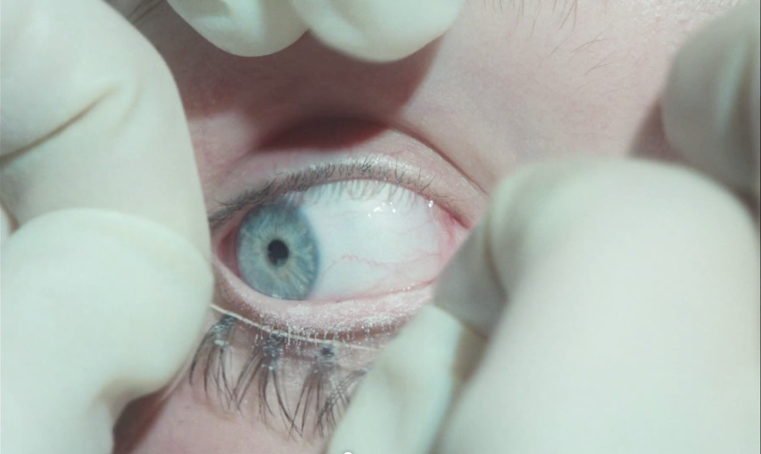

This involves . . . some things. Surgery with ‘Dr Esthetique’, whose tools and technology are, let’s say, Victorian.

Relentless drilling at a finishing school. Elvira’s a talented dancer, in fact, but that only irritates the dancing mistress because she doesn’t have the looks to match.

Aggressive diets, continual scoldings, disgrace and humiliation. Life, in short, is lived by Elvira as an endless punishment for not being beautiful enough.

Now, Elvira herself would love to marry the Prince.

It isn’t about money for her. She’s already in love with him because he’s published a book of poems and she adores them, though she’s too naïve to realise they’re full of sexual innuendo.

She also has a chance encounter with him in the forest, but Disney it ain’t. It’s plain to us hearing him joke with his friends that the kindest word you could use for him is ‘fuckboy’. All their talk is of whether it’s more fun to have a terrified virgin or a woman already ‘broken in’. The instant his mates see Elvira they jovially suggest he rapes her, and he only declines because she still has her nose brace on and he doesn’t like the look of her. Their real game is degrading women, and he can do that without having to make the effort of getting it up.

But poor Elvira’s take-away is that she isn’t pretty enough. She’s a nice girl, but she’s unworldly, and she can’t afford to be.

Meanwhile Agnes’s life going badly too – but it’s a different kind of bad. The beautiful kind.

Agnes’s father dies and her stepmother won’t spend the money to bury him because she’s piling debts to pretty up Elvira. His corpse rots in the castle. It’s horrendous, but the worms that eat him are also silkworms that spin a magic dress for Agnes to wear to the ball later; this is grandiose suffering, the poetic kind in which she gets to be innocent and pure.

The other problem she has: she may be noble, but she isn’t a virgin. She doesn’t want to marry the prince because she’s in love with someone else: the sweet, handsome, devoted stable-boy Isak (Malte Myrenberg Gårdinger). Of course this is all forbidden, and when Elvira accidentally stumbles upon their tryst the wicked stepmother demotes Agnes to the Cinderella kitchen-hand and kicks Isak out, and it’s all very sad.

But it’s sad. It’s not demeaning. It’s a tragic romance, and at least Agnes is getting a romance.

Or that’s how it looks from the Elvira perspective. Agnes gets the grace of a grand, dramatic, elegant set of woes; Elvira just gets continually insulted and blamed and rejected by everybody, her body mauled and her feelings treated as idiocy she isn’t entitled to indulge. Only beautiful girls have any business wanting things.

So of course Elvira is open to desperate measures.

The head of the finishing school is more sympathetic to her than the dancing mistress. Or perhaps she’s manipulative; it’s hard to know.

Of everyone around Elvira, this perfect lady is the only one who acknowledges that what she’s going through is hard. She calls her ‘brave’, telling her that she’s ‘changing your outside to fit what you know is on the inside.’ Later, though, she boasts to friends that she’s the one who changed Elvira and that the girl’s best quality is that she’s ‘obedient’, so how sincere is her kindness? We can’t know.

But she has a suggestion.

One of the problems Elvira faces is that she likes food. It’s not as if much else in her life is comforting, after all, and so she thinks herself fat and is expected to lose weight. In fact Elvira is ‘fat’ in the sense teenage girls use the word, which is to say: she isn’t. She’s one or two dress sizes bigger than her slimmest competitors, with curves most lovers would be thrilled to get their hands on.

Blichfeldt’s camera plays a clever trick there: it can zoom in on this or that bulge the way you do when you’re hating yourself and all you can see is a fault, but it can also frame Elvira in a full nude. I think it may be a body double, because she’s thinner in later scenes and in an interview [link https://www.rogerebert.com/interviews/the-dream-within-the-fairy-tale-emilie-blichfeldt-on-the-ugly-stepsister] Blichfeldt, who comes across as a genuinely lovely person, said ‘I wouldn’t ask an actress to lose weight. I just wouldn’t do that, especially to a young one.’

So it may or may not be Lea Myren we see in those shots, but whoever she is she’s smoking hot. ‘There’s nothing wrong with any of us,’ [link – https://dailydead.com/overlook-2025-interview-with-the-ugly-stepsister-writer-director-emilie-blichfeldt/] is one of the statements Blichfeldt is most passionate about.

But Elvira doesn’t look the way everyone demands, and she doesn’t fit into Agnes’s appropriated dresses, and her life is so miserable that staying on a diet is pretty much beyond her strength. So when the headmistress offers her a tapeworm that’ll eat up all her food for her, of course she’s going to take it.

She does get thinner. But oh boy does she get some extra body horror with it.

Do you know that in Grimm’s version the ugly sisters cut off pieces of their feet to fit the slipper?

By the time we reach that part of the story, what else would Elvira do? Her spirit is broken and her costs sunk.

I’ve spent longer on the plot of The Ugly Stepsister than The Substance because the plot makes more difference there. The Substance is a very simple narrative really, an escalation of events that flows smoothly and rests on a single device and a single character, whereas The Ugly Stepsister is a cavalcade of new horrors coming one after the other until Elvira breaks under the weight of them. Both, though, are campily, Gothically unforgettable.

If beauty horror is a genre, what are its features?

I’ll lay out a few common factors; let’s see where that takes us.

First: the directors are female.

Never say never, I guess, but these are stories about what it’s like to be a woman in a man’s world. The odds of a male director either caring to make such a movie, or pulling it off if he did, are not high.

All the films I’ll mention as beauty horror in this essay – The Ugly Stepsister, The Substance, The Outside and Grafted, the latter two of which are more minor entries that’ll come up later – are directed by women. The Ugly Stepsister and The Substance are the work of single writer-directors, and the other two have at least one woman collaborating on the writer team. They aren’t all equally good, but either way: this is a women’s genre.

Second: life is retro.

The Substance, from its hard colour saturation to its aerobics classes, is pure 80s.

Elizabeth even wears shoulder-pads at one point.

There’s a particular nod to The Shining, which is 1980: the bold carpets and red bathrooms of Elizabeth’s studio workplace are starkly recognisable.

Both in fashion and cinematic echoes, The Substance echoes the decade in which Demi Moore herself rose to fame as one of cinema’s great beauties.

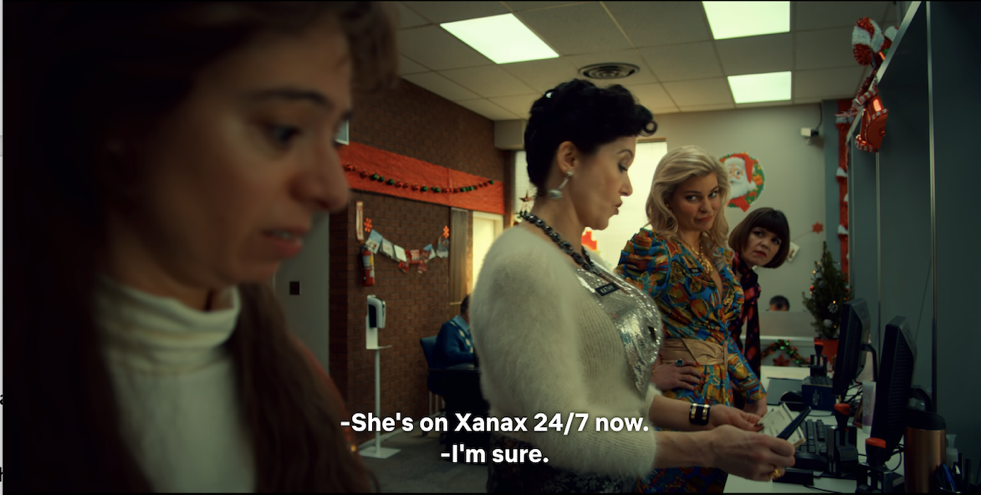

Blichfeldt, meanwhile, enthuses in interview about how much she loves the 70s aesthetic, though with its starred lashes and piled hairstyles I’d say The Ugly Stepsister has a touch of 60s chic as well.

On the other hand it’s heaping with lace and petals in a way very evocative of Peter Weir’s 1975 Picnic at Hanging Rock, with the same soft-hazed quality of image, so yeah, definitely 70s.

These are dreamscape movies, evoking eras that to a female viewer will be one of two things: either a time before you, making them entirely mythical, or else a time you can remember from when you yourself were young and beautiful. (Or at least, you probably think you were more beautiful in retrospect than you did at the time.)

Real enough to feel like the pain they evoke is real too. Unreal enough that there’s room for it to happen on the scale it deserves.

Third: the body horror does not fuck around.

Both movies have a three-movement symphony of distress.

First there’s the misery of not looking the way you should, and being treated horribly on that account.

Second, there’s the terrible things you do to yourself (or let be done to you), and they are very hard to watch.

Third, there’s the terrible unintended consequences of what happened when you went too far, you tried too hard, you cheated. Put another pin in that thought, but let’s just say for now that Sue trying to snatch too much time from Elizabeth and Elvira trying to get thin without dieting are what cause the beginning of the end. You make a mistake and terrible things start happening to your body by themselves. These are also very hard to watch.

Both, by the end, leave the heroine looking far worse than she would have done if she’d just left well alone. Horrendously so.

Fourth: men suck.

In each there’s the odd man who’s young and handsome, but he’s not nice. Agnes’s cute stablehand Isak is an exception, but he gets thrown out of the story and he’s not for the likes of Elvira anyway: for our heroines, handsome young men are also cruel. Elvira’s Prince is handsome, but he’s a predator. As Sue, the heroine of The Substance has a casual hookup with a hot young dude, but when she runs into him as Elizabeth he just yells at her to get out of the way.

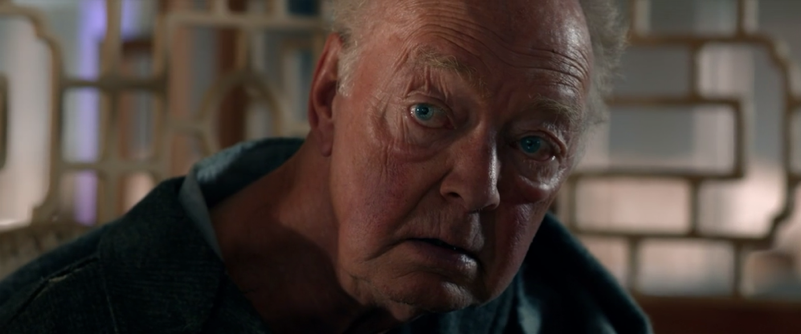

Mostly men are middle-aged or older, unattractive, and slaveringly lecherous. Elvira and Agnes are told that if they don’t snag the Prince at the ball there are runner-up prizes, other wealthy men looking for young brides. The majority are old and all are disgusting.

Elizabeth is surrounded by men who genuinely seem to think they’re invisible; they judge women’s looks at the top of their voices, and if they judged themselves by the same standards they’d have bags over their whole bodies. The shareholders that fire Elizabeth for being over fifty are seventy if they’re a day.

In both movies men are consumers. They stuff themselves with rich food and tip down the drink, while eating disorders stalk women like invisible monsters. They talk about women with more freedom than women talk about cakes.

Men watching may feel this is unfair, but take it from a woman: we don’t think you’re all like this, but this is a form of male behaviour every woman is familiar with. Women can do it too, but generally not so often in front of men; men do it in front of women like it’s part of our moral education.

Nice men, in beauty horror, are really not a factor.

Park the list for a moment because there’s an interesting exception.

There’s a point when Elizabeth runs into an old high school classmate, Fred (Edward Hamilton-Clark), and it’s just a glimpse of an alternative life.

Fred clearly had a crush on her back in the day, has been a lifelong fan, and thinks she’s ‘still the most beautiful girl in the whole wide world.’ He asks her out, assumes she won’t be interested because she’s way out of his league, and Elizabeth forgets about it for a bit. Later she remembers him when she’s feeling terrible about herself, makes a date, and then gets so obsessive as she’s making up her face that she collapses into a heap of insecurity and stands him up.

What would Fred have been if she’d gone out with him? On the one hand, he’s no supermodel: he’s a bit awkward, and it’s clear that what he could offer Elizabeth is mostly his adulation. But on the other hand . . . Well, there’s a glimpse of normality there. Fred looks his age; he’s no more self-conscious about his appearance than any other man in the film, but he isn’t filmed as revolting the way The Substance films most men. More, he actually considers that a woman might not be into him and acts like it matters. He seems kind, and in his dorky way he’s really quite cute.

Most of all, he offers one of the timeless solutions to aging: be with someone who knew you when you were young and still sees that person in you. That’s what ‘for better, for worse, in sickness and in health’ is about; you hook up with someone when you’re still shiny and new and hope to keep shining in their eyes after you’d no longer dazzle a stranger.

High-school Elizabeth evidently overlays Fred’s vision of fifty-something Elizabeth. After she’s gone full ‘freak’ and the world screams at the sight of her, Elizabeth pleads, ‘It’s still me!’ She’s felt that way all the time; we never feel that different on the inside, and through the eyes of love – through the eyes of Fred, maybe – it’s true.

But Elizabeth can’t accept it. A date with a harmless guy who thinks she’s still attractive is too different from the rest of her experience to be believable.

And ask this: if she hadn’t been the beauty of his high school, would he still remember her thirty years later? This is Isak re-encountering an older Agnes, nothing that would ever have happened to Elvira. It’s Elizabeth’s beauty that stuck in his mind; would he be interested in anything else?

Maybe. We never find out.

Fifth: it isn’t safe to be femme.

. . . And here’s where I may make some enemies, because I know most people absolutely love these movies. Certainly they’re beautifully made, they touch on a raw and vital subject, and they’re screaming about something that merits a scream. They have fabulous performances, amazing art direction, dramatic storylines and horrible oozing gore. I think they’re both great.

So when I talk about something I’m less comfortable with, well, it’s because they set the standard so high. Please don’t cancel me.

Remember when I asked you to put a pin in Alma, Elvira’s younger sister? Let’s unpin her.

Alma thinks Elvira’s mad to take the tapeworm. She’s right in that it makes Elvira very ill.

But here’s the complication. Alma looks like this:

More than that, Alma isn’t on the meat-market. Their mother has decided it’s too soon to start husband-shopping for her, and so she’s completely exempt from all the pressures Elvira faces.

Now, I know this is a fairy tale, but that doesn’t quite sit right with what we’ve been shown. Their mother is absolutely desperate to marry the family into money. She’s willing to take on huge debts and cut up Elvira’s face to do it.

Is she really not willing lie a little bit about Alma’s age? Even just as a Plan B? It’s not as if all the perverts of the court aren’t into young girls.

Alma is oddly exempt from all of this. Blichfeldt calls her the ‘one hero’ of the film [link: https://scriptmag.com/subverting-a-classic-fairy-tale-emilie-blichfeldt-discusses-the-ugly-stepsister], and she is – but it’s easier for her to be a hero because she doesn’t have any pressures on her, to a degree that feels just a little bit contrived.

The Ugly Stepsister has what I might call a bit of a blind spot, in fact: pretty girls don’t have to worry about their looks at all. Agnes never thinks about her appearance one way or another, either disliking any feature of it or worrying that it draws the attention of dangerous lechers. And Alma acts completely disconnected from the whole debacle, and the narrative implausibly allows her to be.

And I’m not sure that’s quite right.

Look, I never looked like this.

But I can say for certain that I don’t know any girl or woman, however beautiful, who doesn’t have something about her looks that troubles her, and who doesn’t feel in some way unsafe if stared at too hard.

In The Ugly Stepsister, the hostile glare is only drawn if you don’t look pretty enough. If I was beautiful I wouldn’t have to worry how I looked: no doubt that’s what Elvira thinks, but it might have been a richer film for showing that glare in a fuller spectrum.

What’s the solution to the world Elvira’s trapped in? Well, it’s the help of her sister – but only after Alma starts dressing like this:

After it all falls apart the two of them just leave: they ride off to the country’s borders, Elvira a mutilated goblin and Alma a gorgeous soft butch, escaping the story.

Let’s talk about that on two levels: the literal and the symbolic.

On the literal level – how is it going to help them? They’re penniless and they’re going off with no destination. They may be leaving one fairy tale, but they’re riding straight off into another: this is how you become the Goose Girl or Cap-o’-Rushes, and those heroines only got out of their predicaments by marrying other rich men.

Since this is a fairy tale, the symbolic may be more helpful – but it still leaves us with a problem. They’re leaving the insanity of a world where being a beautiful morsel for the appetites of bad men is your only value, and yeah, wouldn’t we all like to get out of that? But again, where to go instead? In Elvira’s bashed-up face and Alma’s boyish clothing, they aren’t just leaving the insanity: they’re leaving femininity entirely.

The only girl who stays in femininity is Agnes; it’s been natural to her all along and she occupies it effortlessly. She marries the Prince.

Which is a terrible ending for her because he’s a horrible rapist. Femininity was a trap for Agnes as well.

There’s one exception, but you have to age into it.

Body-positive as it is, The Ugly Stepsister is actually full of milfs.

Elvira’s mother (Agnieszka Żulewska) is a fine-looking woman. She refers to herself in the beginning as having ‘saggy tits and two hopeless daughters’ when she’s despairing of finding herself another rich husband in time to pay the bills, but once she moves the pressure off her own shoulders and onto Elvira’s she cheers right up. The night of the disastrous ball she ignores Elvira’s wretchedness because she’s hooking up with a younger man.

The headmistress and dancing-mistress of the finishing school, meanwhile, are also patterns of how a woman is supposed to look; their whole job rests on imparting the tricks of it. But they’re not looking for a husband either: they’re married to each other.

What we see in The Ugly Stepsister is a world in which femininity is a trap for younger women, and safe for older ones – but only if they’ve passed the point of expecting a man to love them. The middle-aged women of this world either give up on love like Elvira’s mother, marrying for money and fucking for casual fun, or they turn to each other. Either you pass the burden of being exploited on to the next generation and exploit men right back, or you withdraw from the male world entirely.

The sanest people are Alma, who looks for beauty in nothing but the beloved horse she grooms, and the ladies of the finishing school, who don’t need anything from men.

And in this world that makes sense – but it’s a pretty bleak world for a femme heterosexual. There are just no good options for such girls.

The Substance is a little more tricky, but there’s something troubling there too.

Female solidarity isn’t much at play in Elizabeth’s world; she has fellow-athletes on her aerobics show but they aren’t really characters, and everybody who has power over her life – whether professional or emotional – is male.

But we also see a male Substance user. And he’s keeping his head better than Elizabeth.

We see him first when he recruits her, played by Robin Greer, glossed up to an eerie, falconish beauty.

Later we see the original version played by Christian Erickson, looking elderly and rumpled. This man acknowledges to Elizabeth that it’s difficult to live this lonely, separated life – but look at him. He’s okay. His young version isn’t leeching the life out of his older self; he may be struggling, but he hasn’t lost his head the way Elizabeth does.

Now, there are diegetic reasons you can give for this. The young man is a doctor; no doubt it’s nice to look so lovely but it isn’t what his career depends on, and he isn’t surrounded by people who degrade him as viciously as men degrade women in this film. You could argue that it’s a story about how beauty standards affect us all but damage women worse than men.

But it didn’t land quite so well for me because Elizabeth’s decisions are – well, they’re not just reckless. They’re under-supported.

It’s quite possible to show someone making crazy decisions under unbearable pressure; The Ugly Stepsister does just that. But The Substance, while it goes hard on that pressure at the outset, goes a little light on it ever after.

Sue, the minute she’s cast, tells the producer that she has a ‘scheduling problem’ that means she can only work alternate weeks, and he accepts it without a murmur. The first time she overstays her welcome it’s because she’s brought home a handsome guy and they’re in the middle of getting it on, and of course it’s frustrating to stop halfway through – but she collapses with a dizzying nosebleed, and it’s very obvious she’s courting physical danger, but she goes and drains more from Elizabeth anyway.

There’s no reason she couldn’t switch and come out of the bathroom as Elizabeth shouting, ‘Stay away from my daughter!’ except horniness – which is not a very strong thematic reason. It could have been played up more if we’d seen more sexual frustration in Elizabeth, or a deeper craving for intimacy, but we don’t. Elizabeth yearns for public praise, shouting crowds; sex hasn’t seemed a big motivator up until it’s suddenly a reason to do something dumb enough to set the horror in motion.

Similarly, Sue starts overrunning Elizabeth’s time badly because offers start flooding in – prime TV spots, the cover of Vogue – and she reckons that if she doesn’t take them the opportunities won’t come again. But we’ve been shown that her producer accepts she has a scheduling issue, and we don’t get shown a scene in which she tries to negotiate and gets told that if she doesn’t show up at specific times she’ll be fired, so again, there could be reasons but we don’t see them. It leaves us with the narrative reason under-dressed: if Sue doesn’t overstay her welcome we won’t get the special effects we came here for.

Elizabeth, meanwhile, precipitates the final cascade of disasters by making a series of rapid mind-changes that . . .

Well, she says lines in the script that explain them. She attacks Sue for stealing all her time, which is self-defense; she then remembers Sue gets adulation and regrets it, saying, ‘I need you because I hate myself.’

So you can’t say the script didn’t provide an explanation. It did, in English, spoken aloud by the lead actress. In the court of public opinion, it can produce documented evidence.

But with everything we’ve been shown – that Elizabeth doesn’t experience any of Sue’s glories for herself and that Sue doesn’t even look like her – it’s a little thin. Sue doesn’t play as if she’s ‘one’ with Elizabeth; they’re two separate consciousnesses physically stuck with each other. It doesn’t do a deep job of concealing the real reason Elizabeth changes her mind so suddenly, which is that if she doesn’t, that’s the end of the story and we want more body horror before we’re done.

It’s perfectly fine for things to happen because the story requires them to happen if it’s going to get where it needs to go. The trick is to put in good enough rationalisations that from the other side of the screen, they feel like reasons. But if you don’t put in enough work on those rationalisations, well . . .

It’s hard not to be left feeling that Sue and Elizabeth are both a bit stupid.

I said this online and defenders said that no, they were just reckless because of desperation, and yes, I’ll admit that we’re clearly meant to read it that way. But when we aren’t shown the continual pressures on Sue, just the temptations? And we see a male Substance user showing better sense? And when we don’t see Elizabeth engage with any other women or take an interest in anything other than her appearance-driven career (despite apparently having once been an Oscar-winning actress, which you’d think gave her artistic aspirations and an inner life as well as an outer one)?

In the real world, I’m calling this a slightly under-developed script, something that could have used one more pass before shooting. But in the world of the characters, it’s just a little hard not to read a touch of shallowness and short-sightedness as well as desperation.

Remember when I said to put a pin in the idea that you lose a fairy tale by trying to cheat? We can unpin that now.

One of Grimm’s tales is of Frau Holle: a good and bad stepsister each get their just deserts. (Thanks to Pamela Freeman for pointing me to that one.) The good girl gets lost in fairyland, works hard for the magical old crone, and is sent home covered in gold. The bad girl – ‘ugly and stupid’ is how she’s described – goes into fairyland hoping to get the same reward, but she slacks off at her work. As a result, she’s sent home covered in pitch she can never clean off.

Elizabeth and Sue get what’s coming to them fair and square by fairy tale logic: they knew the rules and they didn’t stick to them.

But in a fairy tale, that’s what happens to the stupid girl who deserved to suffer.

Fairy-tale logic is merciless in that way: you know the rules, you break them, and your subsequent mangling is entirely your own fault. And while of course a film-maker is free to write whatever story they like, these tales are in our heads somewhere. Even if you haven’t heard a specific one, you recognise the logic of them like you recognise the grammar of your mother-tongue.

The outer skin of The Substance is the story of an innocent victim, but its narrative bones are the story of the girl everyone blames for her own stupidity. The Ugly Stepsister tackles that openly, but in The Substance we just have to draw our own conclusions. If we’re sensible we draw the conclusion that stories about pretty versus ugly girls are unfair – but if you wanted to draw the conclusion, ‘lol, women are crazy,’ it wouldn’t be impossible.

A man who hates women can say that women obsess about beauty because we’re stupid, and if a film tackles beauty horror I really, really want it to close every possible door that might open onto any support for that.

The Ugly Stepsister presents a variety of ways to be a woman or girl and shows the danger of being femme in all of them. The Substance only has one woman – or rather two women with the same personality, doubled once again as the beautiful and ugly sisters. But they’re living the fairy-tale logic in which the ugly one is punished for deliberately trying to get what was freely offered to the pretty one.

At its best it’s a challenge to that old troubling narrative, but it’s a slippery substance to be handling when you’re on the ‘ugly’ girl’s side. Are there any measures a woman who dislikes her own appearance can safely take? In the real world I know someone who had cosmetic surgery – and yes, it wasn’t unrelated to abuse. Her father was a domineering bully who was emphatically clear that her sister was the pretty one. She hated her nose so much that the first thing she saved for as soon as she started earning money was getting it shaved down.

‘And then,’ she says cheerfully, ‘I never thought about it again.’

As far as she was concerned it was money well spent. She changed something that was bothering her and went on her merry way.

Was there anything actually wrong with her nose? No: it’s a family feature and most of the cousins who inherited it did just fine. Would it have been better if her father had been a fair and gentle man who made her feel lovely? Absolutely. But if that’s not where you start from then is the only safe solution to take a not-even-once approach to cosmetic surgery? Beauty horror would certainly tell us so, but sometimes in the real world people aren’t quite so teetotal about it, and it’s not always an inevitable slide into madness.

Both are very good movies, but you can worry at the edges of them if you start thinking too hard. But to be fair, these are savage, angry films, and nuance isn’t what they’re going for. They have a single point to make, and they make it loud, and that’s a mission accomplished.

They aren’t trying to make you think, but to make you feel, and what they want you to feel above all is the desperation that comes from being the ugly one – which, in the real world, is what most women feel like. It doesn’t take in the whole experience of femaleness, but then again most films about masculinity don’t take in the whole range of experiences either and we don’t usually hold them to that standard. Subtle these films may not be, but heartfelt they unquestionably are.

If this is a genre it’s a small one; it’s a subset of body horror and there are few comparisons to make.

It’s also part of another genre staple: the neurotic woman in psychological decline. But compare these to something like Black Swan (2010), which is both body and neurotic-woman horror: its heroine encounters a range of other women who are navigating their own femininity with different degrees of success and struggle, and the pressures that keep her insane get topped up throughout the story.

If you’re going to show your heroine making mad decisions, you have to keep on top of the reasons why. The Substance just slightly rests on its narrative laurels.

This is the explosive quality of beauty horror.

Any scary movie will have someone or something to blame, of course, and there will always be an element of social commentary, either explicit or implied. That’s what makes the genre so interesting. But the forces to blame can be pretty oblique: a demon possessed Regan, there’s something mysterious about the Overlook Hotel, the woods around Burkittsville are all wrong. We can draw our own conclusions.

Beauty horror is something different: it’s satire.

And in satire, you need to be very clear what and who is to blame, and to what degree.

In essence the answer is simple: the societal pressures on women to look a certain way drive women crazy. But then there are the specifics: who inflicts these pressures, and what kind of woman do they madden? Because if your answers to that aren’t very precise, then ‘There’s no good way to be a feminine woman’ can become the accidental implication, which is not quite what feminism is going for.

Let’s compare a slightly earlier example: The Outside from 2022.

This isn’t a film, but an hour-long episode of Guillermo del Toro’s Cabinet of Curiosities series on Netflix. Directed by Ana Lily Amirpour of A Girl Walks Home Alone At Night fame, it’s the story of poor naïve Stacey (Kate Micucci) succumbing to peer pressure.

Stacey isn’t ugly, but she’s not as put-together as her workmates. She has a lazy eye, her clothes are dowdy, she’s plagued by anxiety and she has eccentric hobbies like taxidermy. She obviously doesn’t fit in.

Fitting in wouldn’t improve her, mind, because her workmates are horrible women.

Their entire conversation is spiteful gossip about other women and flattering each other. But they’re a tight-knit clique with their own style, and Stacey doesn’t have friends outside work and she doesn’t have the confidence to step back and see that these petty madams aren’t worth worrying about; she desperately wants to be part of things.

Amirpour is careful about what she shows.

We see that Stacey has a nice husband who loves her as she is; perhaps even more important, we see another woman who manages all right. She’s not an inner circle member of the clique but she’s equally pleasant to both the Mean Girls and to Stacey; she’s healthy and happy with what she’s wearing and she’s doing fine.

But Stacey is insecure; she imagines that the Queen Bee’s ‘whole life is like a catalogue’ and she thinks that’s a good thing. More tellingly, she says, ‘She could walk into a room and make friends with anyone, you know? Imagine that.’ She attributes the cliquishness to ‘Just women,’ but that’s a rationalisation. What Stacey wants is to be less frightened and insecure, and she’s fascinated with women who seem not to be.

There’s lots of ways to be a woman in The Outside, and you don’t have to give up femininity. Locating femaleness within a very limited look and style is something done by Stacey’s nasty colleagues, because it’s a power move for them, and by Stacey herself, because she’s tired of her anxiety and thinks that if she looked confident she’d feel confident. As the title says, she’s trying to change a real problem by coming at it from the outside.

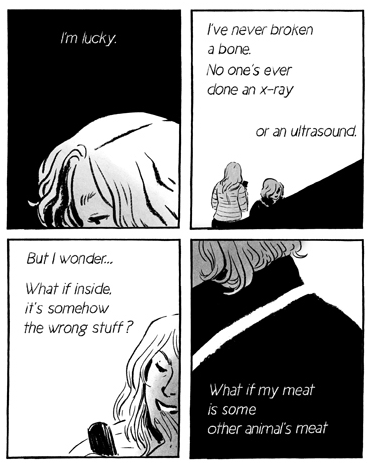

The episode is an adaptation of an online comic by the extraordinary Em Carroll, which has the unforgettable title ‘Some Other Animal’s Meat.’ I won’t try to summarise it because it’s short and you can read it here: https://www.emcarroll.com/comics/meat/

It’s a very different story; Carroll’s work always resonates more with the symbolic than the literal, and what’s dream and delusion versus what’s real is very much in question. (Which is another reason I don’t want to summarise it; you can’t summarise Carroll without missing the point.) But it’s a tale of alienation that comes from within, not from the outside, of a state of mind in which your own humanity does not feel altogether real to you. The protagonist isn’t worried about her appearance as such; she’s plump and middle-aged, well-presented externally, and what she dislikes about her body is that it’s a body at all. Beauty doesn’t trouble Carroll; her mind is on stranger things.

Amirpour’s adaptation takes just the basic elements – cosmetics parties, a moisturiser called Alo Glo, and a neurotic woman with a kind of doppelganger self – and that’s fine.

Carroll herself was a co-writer, so we can call it officially approved. Even if it wasn’t, it would take David Lynch to do something in the same spirit as Emily Carroll, and Amirpour makes the smart decision to play to her own strengths.

Stacey is allergic to Alo Glo in the same way she doesn’t ‘match’ with her colleagues, and her refusal to accept that both of these things are okay is what drives the story into horror.

This is a case of beauty horror where being femme is all right – the nice co-worker is reasonably femme – but what’s not safe is fakery. The Ugly Stepsister’s way out of the madness is to abandon either femininity or youth; The Substance doesn’t have one, just buckets of blood’s worth of rage to express how mad it truly is. In The Outside you do have the option available to us in the real world, which is try to ignore some of the worse messages and muddle through somehow. It’s just that Stacey doesn’t have the confidence to take it.

By the other criteria I was laying down: yes, it’s retro in style, specifically 80s. The body horror is constrained by budget, but there’s definitely an unpleasantly raw look and some nasty scratching scenes as Stacey’s skin reacts to the Alo-Glo. The taxidermy is a good move too: some genuine yuck happens in those scenes, so if you’re a gorehound there’ll be enough to keep you happy.

What’s different is that men don’t suck.

Somebody has to suck in these movies, but it turns out it doesn’t have to be men. It has to be the people that the pressure is coming from, and in this case it’s the women at work. Stacey’s husband ends up a victim because his unconditional love for her original self stands in opposition to her longed-for new self.

The end result is that it’s not Stacey who ends up being a physical grotesque. She ends up looking like this:

The body that ends up in grotesque disaster is that of her poor loyal hubby. The Outside tells the same story, but it swaps the genders. Women are to blame for the societal pressure, and so the doubling happens not between the protagonist and her sister or doppelganger so much as it does between the self her husband loves and the self she wants to become. With women the villains, a man takes on the final physical fall.

Beauty, in these stories, is magical, and hence elusive. Sometimes someone or something beautiful gets out of them alive, but only sometimes. What remains constant, always, is that somebody’s body gets destroyed – and it’s the body that can’t let go of the truth. It contains the knowledge of what the old self really looked like, and even more dangerously, that the reviled old body had feelings, had value, belonged to a real human being who was hurt by all the rejection.

In short: someone’s body bears the punishment for wanting the ‘ugly’ self to be loved without having to be ‘beautiful’.

That body might belong to the woman herself: that’s what Elizabeth wanted, and Elvira even more so. But it might also, like Stacey’s husband, be someone who didn’t want her to change because he was prepared to offer that love. If you see the humanity in an ‘ugly’ woman, you take on the full burden of her ugliness. Your body ends up as destroyed in the end as her self-esteem was from the start.

Beauty is escape in these tales, and if you can’t subdue your heart – if you can’t stop hoping that love and imperfection could belong to the same person – then the imperfections ruin you. Walk that tightrope and you’ll dazzle the crowd, but never, ever look down.

These are tales of zero-sum beauty; there may or may not be a winner, but there’s definitely a loser. The lovely princess is an option; the broken ruin is the truth underneath. In the end, the pain can’t be concealed. You can put on as much make-up as you like, but once you’ve been shamed and rejected there’s an ugly husk of a self somewhere in your psyche. These films just make sure it has a physical expression.

So let’s revise the criteria in the light of this contrast. Beauty horror is:

- Made by women.

- Fairy-tale in logic.

- Mythically retro in style.

- Outlandishly, surreally gory.

- Populated by grotesque antagonists who enforce a beauty standard based more on hatred of women than love of beauty.

- Troubled by the question of whether one can be both feminine and sane.

- Driven by double selves – usually both in the before-and-after versions of the heroine, and on women that she envies for being what she isn’t.

- At the end, someone’s body ends up mutilated and/or mutated; that someone will be whoever wanted the ‘ugly’ self to be loved unconditionally.

That seems to work so far.

As long as we’re being thorough . . .

For completeness I also watched Grafted by Jess Hong on Shudder, another 2024 offering in which a neurotic female heroine goes nuts in an attempt to make herself look ‘beautiful’.

The fact that it’s around goes to support the theory that beauty horror is having a moment right now. I was hoping for more to add, but honestly Grafted is so mid that I can’t think of much else to say about it. It’s a movie that exists.

To sum up: Wei, a Chinese student with a birthmark on her face, moves to New Zealand on a science scholarship; she pursues a new semi-magical skin-graft that lets her graft on the face of her mean-girl cousin after accidentally murdering her (never mind how); after that she just gets into the swing of things and starts murdering and face-stealing everyone.

It doesn’t work very well. Partly it’s that the most interesting visuals are when the skin graft goes wild and completely covers people at the beginning and end, but with her it keeps falling off instead.

But really it’s a question of storytelling, because Wei’s motives aren’t very strongly delineated. Is it her birthmark that puts people off her? There’s some talk that it’s a family curse, but that never gets explored. Is it that she’s Chinese in New Zealand and experiencing culture clash? There’s another girl managing to be femme successfully; she comes from Tongan heritage and is sympathetic to Wei’s feeling foreign and out of place, but Wei does her in too for no very great reason, so that doesn’t go anywhere. Is Wei just socially awkward? Yes, but she’s also under-characterised.

What we might say is that it’s a stand-out example of what happens if you don’t write beauty horror very carefully.

Grafted does fit the criteria I laid out, although its visual style isn’t lavish enough to be anything more than some hardcore 90s costuming in the popular girls, and the character writing doesn’t go far into how much of their attitude to Wei is about beauty and how much is xenophobia.

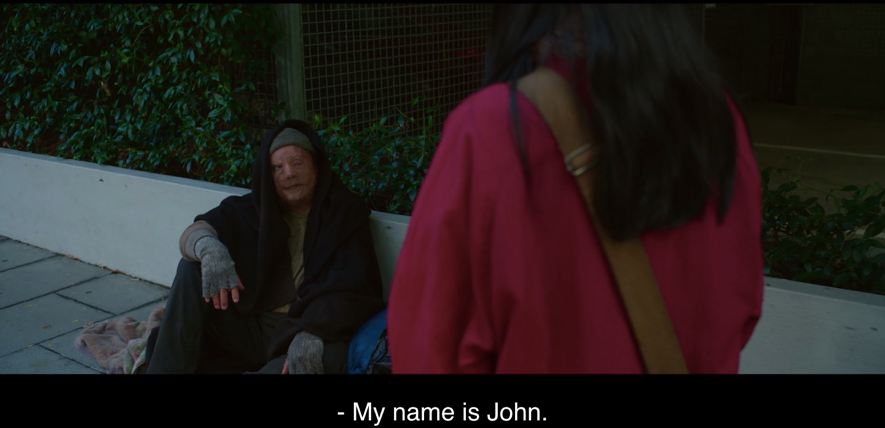

It even confirms the theory that it’s the body that pities the ‘ugly’ girl that suffers. Wei finally melts into a grafted nightmare, and as she does her rampant skin also consumes John, a homeless man who was nice to her, birthmark and all.

John’s own face had burn scars and Wei was pleasant to him, so he was her friend: inner beauty is all he was in the market for. So he ends up melded to her. Another man who didn’t care about imperfections bites the dust; I guess Fred was lucky that Elizabeth stood him up before the full monstering started.

But with the bare points laid out, the story less well-managed and the gore less gorgeous, where does it leave its understanding of women?

You end up assuming that a girl’d do anything to be beautiful, to the point you see no need to develop much in the way of character. You also assume that once she starts chasing beauty she obviously goes crazy, to the point you don’t have to justify it very much with narrative provocations.

You can’t say that of The Substance or The Ugly Stepsister, which are both much better films, but they both do leave us with the difficult sense that being femme and being crazy for beauty are inextricable. They’re neurotic-women movies with no sane women, or at least none that don’t opt out of femininity altogether.

Having said that, I want to be clear that I’m not calling them bad films. They absolutely aren’t. The Ugly Stepsister in particular is a beautiful and hideous treat; it got less fanfare than The Substance but I’d recommend it more highly. If both are a bit more reckless in catching all feminine women in their machinery than The Outside, they’re also far more striking visually and go all-out with the body shocks in a way that’s impossible not to respect.

These films are cries of distress, and nitpicking is missing what’s there.

The Substance is essentially a scream of rage; Fargeat told Elle that ‘The violence in the movie was really a way to take out all the violence that I felt within me. [link: https://www.elle.com/culture/movies-tv/a62297701/the-substance-coralie-fargeat-interview/] She said something similar to Vogue: ‘I wanted to explode and shatter everything in a violent and uncompromising way because to shake this, we need an earthquake, a tsunami. We don’t need to move this – we need to change the whole foundations of society.’ [link: https://www.vogue.co.uk/article/coralie-fargeat-interview-the-substance].

Women tend to turn our fury in on ourselves, and that’s what The Substance is: a self-annihilation that enacts, bloody and visceral, just how grotesque it feels to be subject to such impossible demands. If it hurries over some plot points, well, rage is a fast-moving emotion and doesn’t stop to worry about the details. It calls vividly to mind what Virginia Woolf said about George Eliot’s heroines:

The ancient consciousness of woman, charged with suffering and sensibility, and for so many ages dumb, seems in them to have brimmed and overflowed and uttered a demand for something – they scarcely know what – for something that is perhaps incompatible with the facts of human existence.

And sometimes incompatible with the limits of human flesh.

The Ugly Stepsister, meanwhile, is charged with deep compassion, which is a lot to say about a movie that involves vomiting tapeworm eggs. If it doesn’t find a solution to femininity, well, that’s asking far too much of any one film, and films that pull off complete solutions have to do it by limiting their scope.

I mentioned Black Swan, but while I’ll ride or die for that movie, it also has a more specific subject than just femaleness: its heroine isn’t just a woman but an artist, and has one particular dramatic role she needs to dance. Likewise The Outside is a good little movie, but by the very nature of its brief it has to be less ambitious than either The Substance or The Ugly Stepsister, and so can’t be as memorable.

What, in the end, can we really say to a world that makes women feel like this about ourselves? If there was a solution that could be fitted inside a movie, it wouldn’t be the kind of problem it is.

Let me tell you the most horrifying thing of all that I saw during the writing of this essay. After I watched these movies, do you know what ad YouTube’s algorithm chose to shove in my face? As in, the very first choice once I’d stopped watching?

It was for Oil of Olay moisturizer, and it made me this promise:

Drastic results without drastic measures.

That’s right: drastic results without, oh, such a delicate way to phrase it, ‘drastic measures.’

Watch two satirical movies about the horrors of beauty for women and the world decides that means you’re in the market for a miracle goo to put off the inevitable day when you’ll finally have to succumb to a facelift.

Then the next advertisement was for chocolate.

I don’t know whether to laugh or cry. Possibly it’s time to whip up some Kensington Gore; look, I even found a recipe for it: https://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/p00bktss.

If you need me, I’ll be hurling blood around. Sometimes there’s no other way to express your opinion.

Horror Features on Ginger Nuts of Horror

If you’re a fan of spine-chilling tales and hair-raising suspense, then you won’t want to miss the horror features page on The Ginger Nuts of Horror Review Website. This is the ultimate destination for horror enthusiasts seeking in-depth analysis, thrilling reviews, and exclusive interviews with some of the best minds in the genre. From independent films to mainstream blockbusters, the site covers a broad spectrum of horror media, ensuring that you’re always in the loop about the latest and greatest.

The passionate team behind The Ginger Nuts of Horror delivers thoughtful critiques and recommendations that delve into the nuances of storytelling, character development, and atmospheric tension. Whether you’re looking for hidden gems to stream on a dark and stormy night or want to explore the work of up-and-coming horror filmmakers, this page is packed with content that will ignite your imagination and keep you on the edge of your seat.

So grab your favourite horror-themed snacks, settle into a cosy spot, and immerse yourself in the chilling world of horror literature and film. Head over to The Ginger Nuts of Horror and embark on a journey through the eerie and the extraordinary. It’s an adventure you won’t soon forget!