On Not Adapting Junji Ito. Filming the unfilmable: Uzumaki, Ringu and the power of ‘and yet’

How often have you watched a low-quality adaptation of a great book and got really irritated? It seems like it shouldn’t have been this hard. The book was right there for them to study! How could they have made it this bad?

Why didn’t they just stay faithful to the original?

Well, I get it. But sometimes . . . well, let’s descend into this deep, dark well and see what we find at the bottom. Because I have an idea I’d like to take you through: that sometimes the best time is to be had by accepting that a straight adaptation can’t be done . . . and yet.

There will be a lot of ‘and yet’ in this review.

Now let me ask you another question:

How do you feel about scary pictures?

If you like them, read on. I can promise one thing: I will (with a tiny exception) only be including images from one of Junji Ito’s works – Uzumaki, the hefty book under discussion.

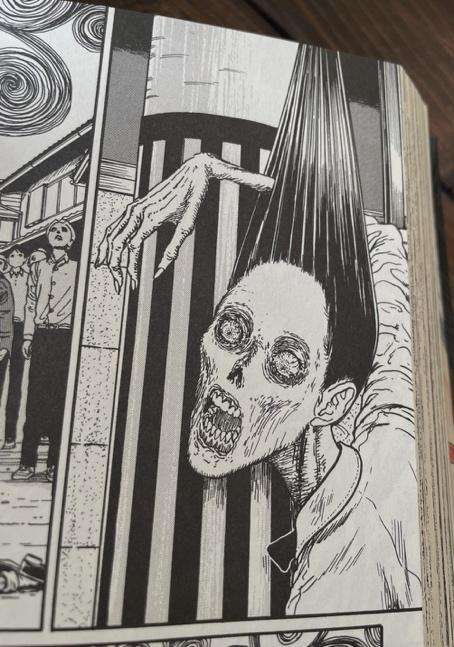

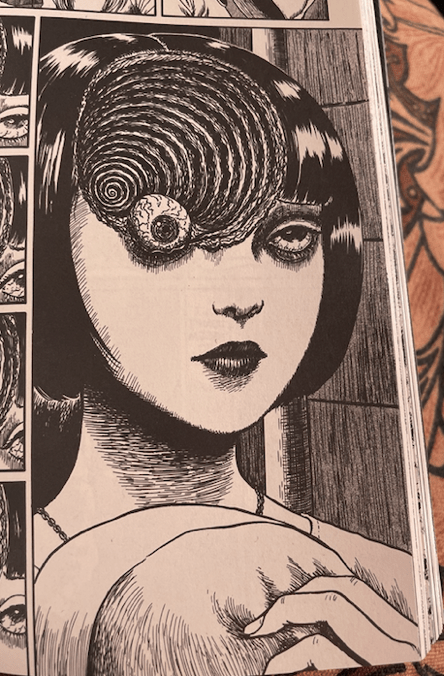

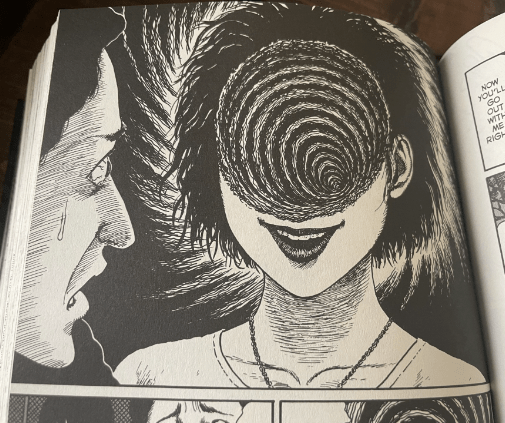

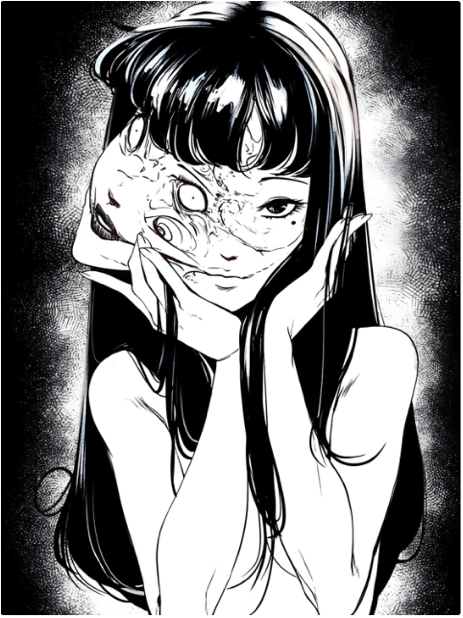

If you haven’t heard of it or him, I guess that’s where we start: Uzumaki, meaning ‘Spiral’, is one of the most famous works of horror ever to come out of Japan, and Junji Ito one of the most famous horror artists. What he does is manga – what we’d call comics or graphic novels – and he is both writer and draftsman. He’s famous for both, and there’s a reason for that.

You will love his pictures. I’d bet a tooth on that. But what I’ll share here won’t give you the full story in any sense.

The majority of Ito’s work – arguably even the best – is his short story collections. I own plenty, but I’m not going to spoil them by sharing images. I’m not even going to share the most important shock-pages of Uzumaki; I respect his timing too much to mar it. This is a man who can make a page-turn into a jumpscare, and they deserve to be encountered in the wild.

If you don’t like scary pictures, I wish you well and advise you that you are reading entirely the wrong article. Now’s your chance to get out before you see things you will never unsee.

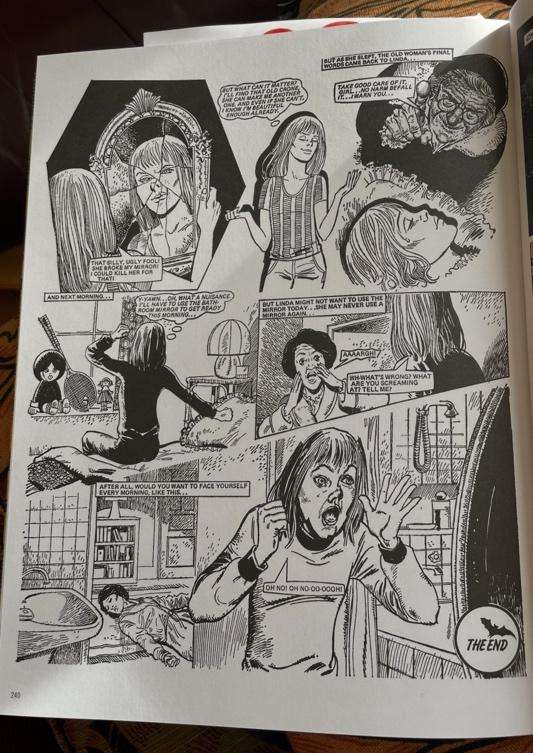

If I was going to describe Junji Ito to anyone who remembers an analog childhood, I’d say this:

Do you remember those old newsagents? The disreputable ones – a row of chocolate bars and boxes of pick-and-mix labelled with 1p or 2p chews you foraged up with grubby fingers; envelopes and papers; tacky air fresheners for cars; magazines all across the racks. A mix of magazines from a wider and weirder world than any one person could expect. Car maintenance mags. Gardening mags. Trade mags. Girlie mags with nipples akimbo, a few shelves higher than the kids’ comics. True crime mags with knives and wounds on the covers, eye level for adults or children depending on how much the owner could be bothered to think about it.

Horror comics. Think of those. Pick one up, have a leaf through. Say you’re a bit new to this kind of thing, but the proprietor’s having a smoke and reading his paper and the dazed sunlight’s streaming through a dusty window half-blocked with ads for rental bedsits and free kittens and discreet massages. No one’s going to notice you. You’re just a little out of everyone’s sight.

You flip the pages, standing in this tatty, ordinary, taboo, open-to-the-public liminal space. And you fall into a dizzying world ruled by violence and unreason and sheer cosmic malice.

You look up. The world feels tainted. Out of kilter. It contains something you didn’t know was there.

What did you just read?

If you had that feeling as a kid, you’ll remember it. Or if you never did, it might still speak to you; it’s a potent private rite of passage, being shocked to find that people actually write stories that dark and nobody stops them. But you’re a grown-up, and these days you’re harder to scare. You couldn’t ever feel that way again, could you?

You may not know it, but you’re already a fan of Junji Ito.

If I was going to describe Junji Ito to a literature lover, I’d say this:

Think of the ghost stories of M.R. James. Elegant. Erudite. Delicately poised, matter-of-fact. Even to this day, frightening.

Ito himself is an open and passionate fan of H.P. Lovecraft, and you can definitely see the influence, but even Lovecraft’s admirers don’t tend to think of his greatest virtue as being frightening. You can’t say that of James. Think of the moments where James makes the whole world eerie and threatening. Take this passage from ‘A Neighbour’s Landmark’:

There thrilled into my right ear and pierced my head a note of incredible sharpness, like the shriek of a bat, only ten times intensified – the kind of thing that makes one wonder if something has not given way in one’s brain. I held my breath, and covered my ear, and shivered. Something in the circulation: another minute or two, I thought, and I return home. But I must fix the view a little more firmly in my mind. Only, when I turned to it again, the taste was gone out of it.

The sun was down behind the hill, and the light was off the fields, and when the clock bell in the Church tower struck seven, I thought no longer of kind mellow evening hours of rest, and scents of flowers and woods on evening air; and of how someone on a farm a mile or two off would be saying,

‘How clear Betton bell sounds to-night after the rain!’; but instead images came to me of dusty beams and creeping spiders and savage owls up in the tower, and forgotten graves and their ugly contents below, and of flying Time and all it had taken out of my life. And just then into my left ear – close as if lips had been put within an inch of my head, the frightful scream came thrilling again.

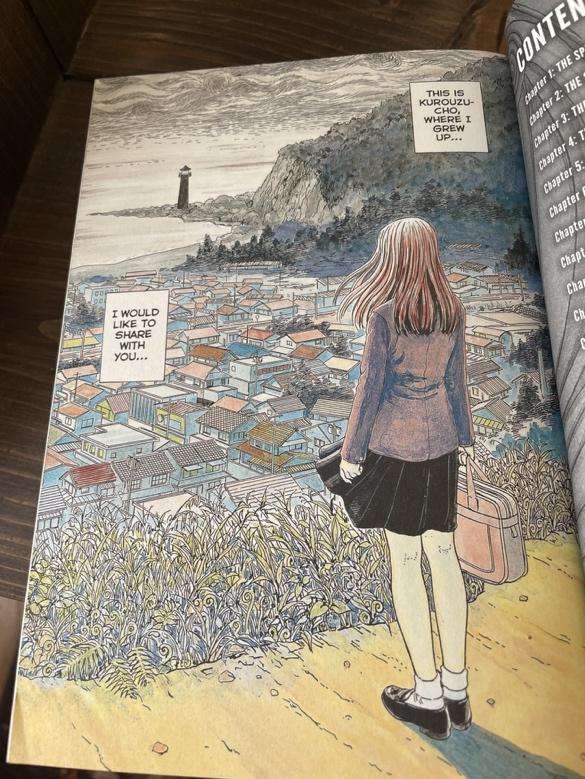

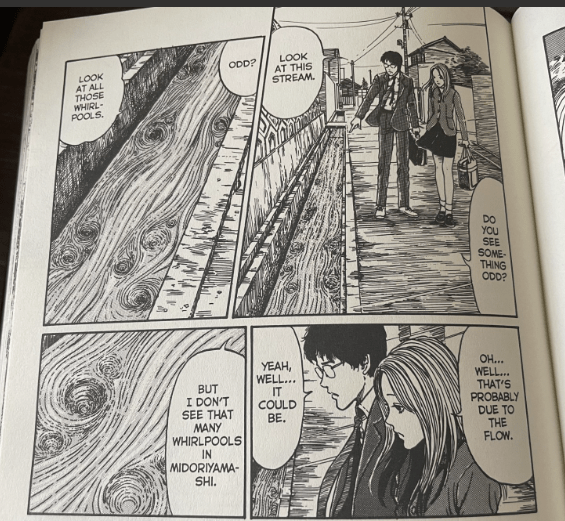

Now enter into Uzumaki – translated for the English-language edition as Spiral Into Horror, though ‘vortex’ might capture the spirit a bit better.

The story takes place in Kurouzo-Cho, a small, ordinary-seeming coastal town in Japan, except for one thing. One tiny, cosmic, inescapable thing.

Kurouzo-Cho is contaminated with spirals.

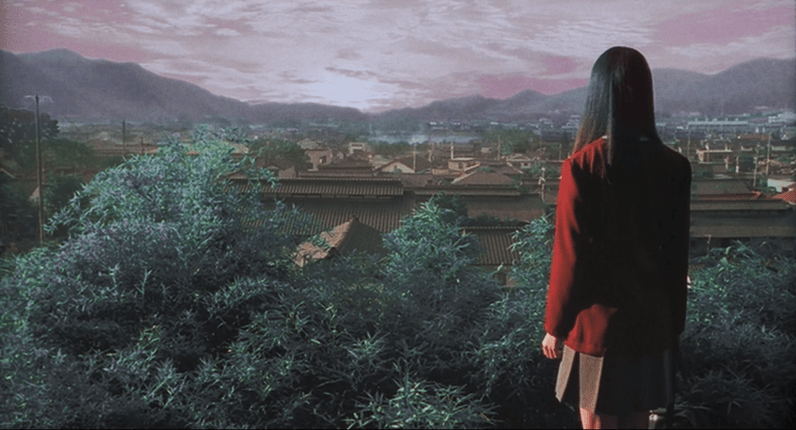

Meet Kirie, our heroine. Well-meaning, sensible, sane.

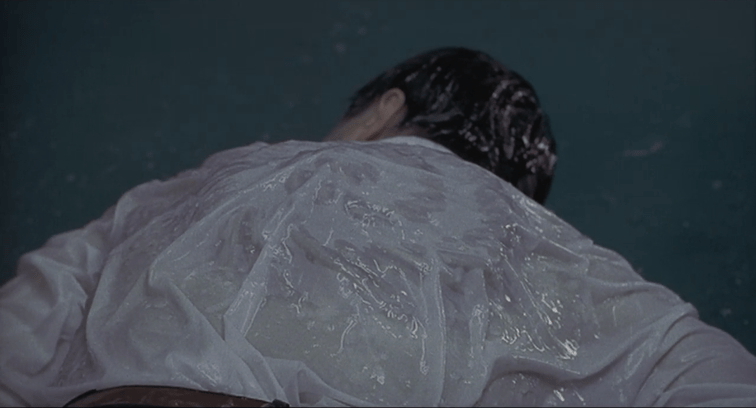

Do you see the way the plants curl at her feet, and the clouds coil above? By the end of the story you will know what that means. You just won’t be able to help her.

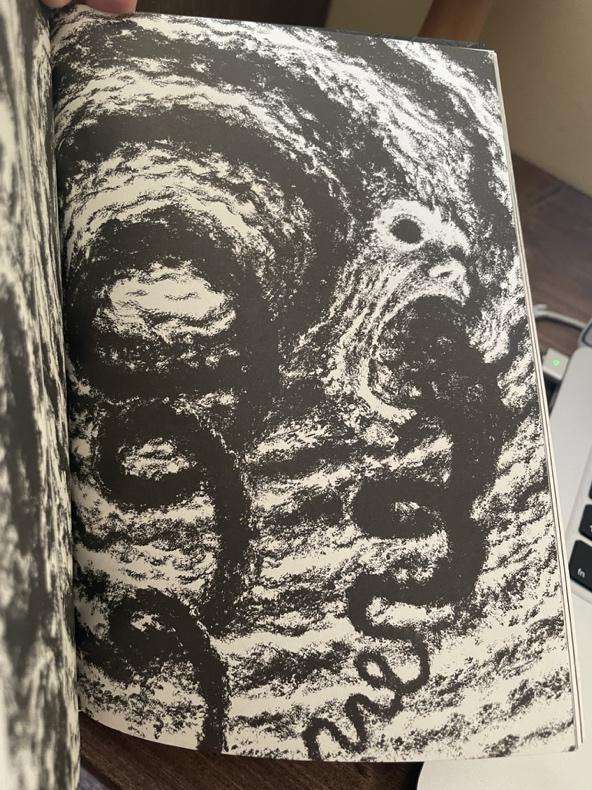

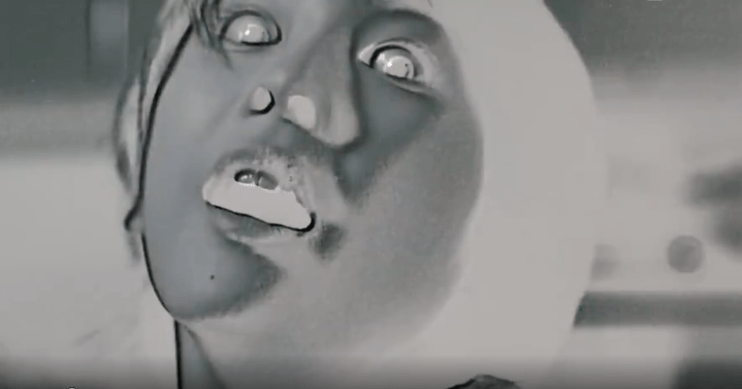

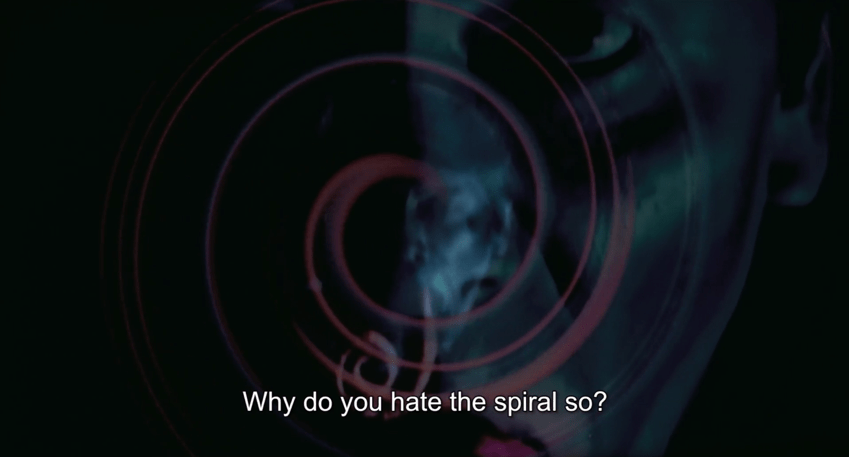

Well, I say the end. By chapter two, here’s what the smoke is doing above the crematorium after her boyfriend’s father, shall we say, spiralled himself to death.

When I say he spiralled himself to death, do you think I mean that figuratively? I do not. It was more physical than you’d imagine.

Are you imagining it now?

No. It was much worse than that.

Junji Ito is the best living horror writer in the world.

And I will die on that hill. Grotesquely. Voraciously. Horrifically.

Beautifully.

And that’s a problem for anyone adapting him into a format that moves.

His linework is so precise, so careful, so extremely delicate, that every page is a work of art. I’m a big enough devotee that I actually went to an exhibition in the Tate, and saw up close how carefully in the days before Photoshop he’d cut and patched together scraps and images to create a perfect whole on the page. A gallery was a good place to put it.

But reproducing that level of detail outside a still image is pretty much impossible.

The natural medium for adapting manga is anime, and indeed a whole industry exists in Japan where the manga acts as a kind of road-test and if it does well enough an animated series will follow. It’s one reason why Japanese anime often has unusually good plots for popular TV.

(I mean, there’s creepy fetish stuff too, but there’s also some very solid storytelling for normal people. If you liked Squid Game, let me recommend Kaiji: Ultimate Survivor, which is the inspiration for Squid Game, better than Squid Game, and makes you so tense you could scream. The app Crunchyroll has a lot of good stuff for free if you’re prepared to sit through some ads.)

And there is anime horror out there.

For instance, you can watch Japanese Tales From The Macabre (2023) on Netflix – except you needn’t bother.

The ‘tales’ are all Junji Ito’s, and the images are bland and flat, and the fan reaction was universally . . . ‘disappointed’ doesn’t even cover it. ‘So inferior that people who knew the difference lost a little of their faith in humanity’ is more like it.

It’s really bad.

It’s also ploddingly faithful – Ito with all the energy stripped out. But technically faithful. Keep that in mind.

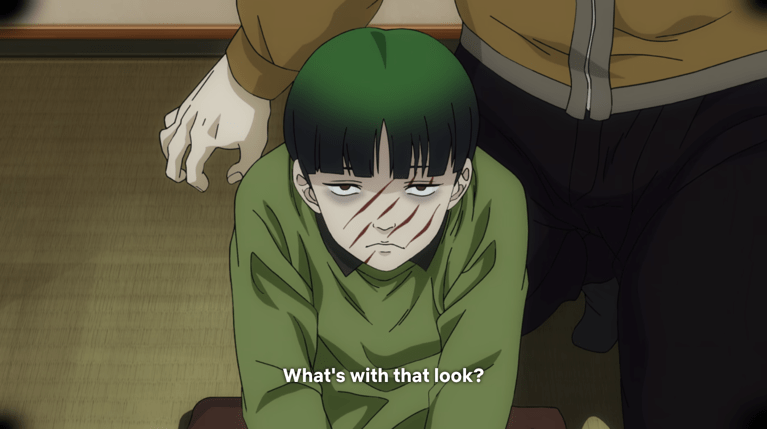

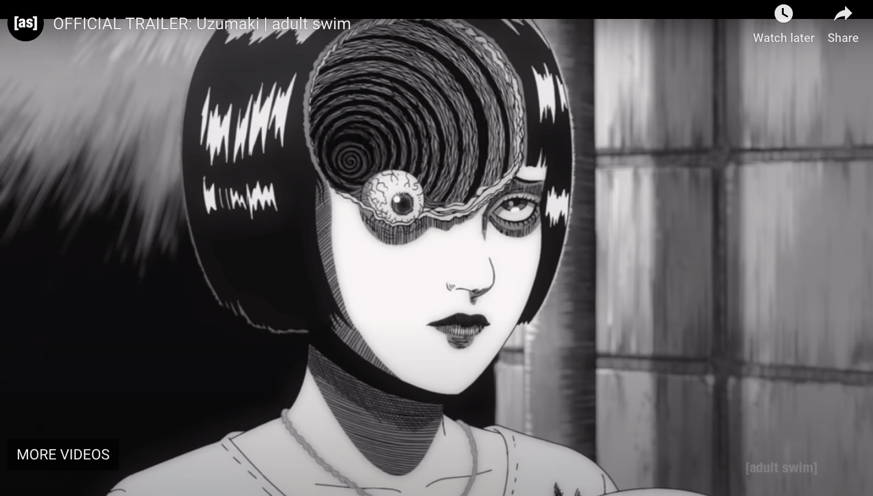

More recently an attempt at animating Uzumaki was aired in the West by Adult Swim.

I’ll cop to not having watched it, partly because I don’t get that channel but also because I didn’t see the point: Ito is a master of his form, and that form stays still and looks back at you with its abyssal eyes.

From what I can gather the first episode was adequate but not as good as the manga, and from there budget limitations and questionable writing choices made for a dingy downhill quality slide. Fans happy to get a half-decent adaptation were prepared to take what they could get, and it wasn’t terrible, but nobody’s socks were blown off.

What I definitely can say is that if you look at images from the trailer – the place they’ll be putting their best foot forward – the same problem applies. Not as dishearteningly bad as in Japanese Tales From The Macabre, but there’s an inevitable loss of quality that makes watching the adaptation feel a bit pointless.

Probably some people reading this enjoyed the recent adaptation and if you did I’m happy for you, but for myself I simply didn’t see any reason to seek it out.

Some things just don’t transfer very well from one medium to another; the gains we make are not worth the losses.

And in the case of Junji Ito, what can film add? Music, movement and sound, certainly, and I’m sure there’s a great composer out there who could do something amazing with Ito’s atmosphere – but they don’t feel necessary to get the full point.

The main virtue of an adaptation is usually a dramatic performance. Norman Bates is disquieting on the page, but Anthony Perkins on the screen? Well, that’s a range Robert Bloch couldn’t give in his plain prose: Norman’s slightly off-kilter vulnerability, his sudden shifts in affect, his delicately balanced artificiality . . . see, I’m having to use a lot of big words to describe it. A fine actor, though, can do it all with the tone of his voice and the turn of his face. That’s great stuff.

But it’s character, and character isn’t really what Ito’s about. His monstrous characters are obsessions incarnate, so wild that they live more in the visual than the social. His normal characters are very, very normal, because what happens to them is all that matters. There’s only so much you can do with a character performance when you aren’t in a character drama, and the best actor in the world could only add so much to Junji Ito. There isn’t all that much to perform, because there doesn’t need to be.

So yes, dramatisations can add things – but they can’t compensate for the subtlety of line they have to strip out. What they can add doesn’t enhance the story, and what they take away guts the horror.

So if I was going to describe Junji Ito to a filmmaker looking for something cool to adapt, I’d say this:

For the love of ink, don’t try. You will annihilate your reputation.

There is just about no graphic storyteller in the world who carries with them that combination of:

- Passionate fans who will get saltier than Lot’s wife if you don’t do him justice.

- Brilliant artwork that can’t possibly be reproduced for film without losing the subtlety on which it depends.

- Examples of said work incredibly easy to show so that critics can do exactly what I just did: contrast his work with yours so people can see at a glance the gap in quality.

You’ll understand, then, that when I saw that the live-action version of Uzumaki was on Shudder – made in 2000, directed by the almost unknown ‘Higuchinsky’ (aka Akihiro Higuchi) for a budget of $1 million USD – I have to confess that if I wasn’t writing this column I wouldn’t have bothered with it either.

However, Jim lets me get away with shenanigans – and one of the shenanigans he allows is that while this column is technically called ‘What’s On Shudder?’, I veer off to talking about other stuff by way of comparison all the time. Shudder is honestly an excuse: it offers a manageable selection and I don’t have to drag my chronically-painful backside into my uncomfortable local cinema. Sometimes I discover unexpected marvels like The Devil’s Bath [https://gnofhorror.com/the-devils-bath/]; sometimes I only have bad things to say and the solution is to talk about other stuff that provides a refreshing contrast.

So I looked at the Uzumaki live-action, and two thoughts occurred to me.

One: I rubbed my claws and cackled at the prospect of recommending Junji Ito’s original work to those poor benighted souls as yet unscarred by him.

Two: I noticed the date.

2000. That was quite the time to be making a horror movie in Japan.

This is a review about adapting the unadaptable, and 2000 was the year to think about it. Because another movie had just come out that formed the perfect contrast to Uzumaki.

If you were a Japanese horror director around the turn of the century you were onto a good thing: the world had sat up and noticed, and starting talking about ‘J-horror’ as a genre. Takashi Miike had been around for ages and Audition (1999) had been an unusually big hit for him, but international audiences had started following a new trend – even if they could count the really notable examples on one withered hand.

Two fingers, really, if you want the ones everyone has heard of. There’s Ju-On/The Grudge, made in 2002 – and in 1998, there was Hideo Nakata’s Ringu.

Oh boy, was there Ringu. A horror film released in 2000 Japan could not possibly escape comparisons; it’s probably the reason Uzumaki got an international release, maybe even why it got funding at all. Ringu cast a long shadow, and the film Uzumaki was made within it.

Here’s the curious thing about Ringu: it’s a better Junji Ito film than any of the actual Junji Ito films.

Not literally, of course. It’s based on the novel Ring by Koji Suzuki, popularly known as ‘the Japanese Stephen King’. Not 100% faithful – you can read Nakata talking about some decisions he took here https://web.archive.org/web/20010210235041/http://www.horschamp.qc.ca/new_offscreen/nakata.html, notably changing the lead from male to female. Suzuki’s tone is more hard-boiled sour than Nakata’s hypervigilant sorrow. Suzuki’s tale also has an issue with intersex people which Nakata kindly stripped out, and his explanations have a more sci-fi flavour than Nakata’s. But Ringu is definitely recognisable as Suzuki’s concept; it is an adaptation.

And yet.

If you’re interested in horror enough to be reading this I assume you know what Ringu’s about. I’ll take it on in more detail below, so for now I’ll just say: it’s the story of a cursed videotape. Watch that tape and it just seems odd; seven days later, you die.

It seems simple; it’s certainly not as symphonically crazed as anything out of Ito.

And yet I can’t imagine anyone who loved Ito who couldn’t love Ringu. If someone asked me for a film that was ‘like Ito’, I wouldn’t recommend an Ito adaptation. I’d recommend Ringu.

What’s going on with that?

We’re talking about adapting an artist who’s spiraliciously hard to adapt – and that means we may find ourselves in the realms of the spiritual adaptation.

Let’s try this idea: sometimes a movie descends from the same fear as a book.

And sometimes siblings bear a stronger family resemblance to each other than a child does to its parent.

That’s why I was talking about M.R. James above, even though Ito himself is a Lovecraft guy. James and Ito don’t have anything to do with each other . . . except that each is a master of chilling, slow-creep horror. Brothers under the goose-fleshed skin.

You could say the same thing about Ringu and James’s stories, in fact – and I’ll talk about it for a few paragraphs because it’s a good example of what I’m talking about. Different times, different cultures, different mediums . . . and yet.

And yet it translates perfectly. Both James and Nakata operate on the horror of the slow count-down – something’s coming, and you know it’ll get to you. Sometimes they even give you a literal time: Ringu makes much of there being seven days, while James had a lot of fun with there being three months in his short story ‘Casting The Runes.’

And there’s another reason why, though I love the old BBC adaptations of James, I think Ringu captures his spirit better. James can be tricky to adapt because so often the danger is awakened by reading; that makes a reader feel more endangered than a viewer. But Ringu is about dangerous watching. Both play off their own form to trace a finger across your dread of forbidden knowledge: you see something, and then it sees you. And in both cases, what rises unburied is thin-boned and glaring and hideously tangible.

Let us be introduced to the actors in a placid way; let us see them going about their ordinary business, undisturbed by forebodings, pleased with their surroundings; and into this calm environment let the ominous thing put out its head, unobtrusively at first, and then more insistently, until it holds the stage.

That’s James introducing ‘Ghosts and Marvels’.

That’s Ringu. The clock ticks, and its echo shudders our marrow.

Do you see what I’m getting at here?

Sometimes works of art have a kinship with each other that makes them better equivalents than literal adaptations. One may not be the child of the other, but they descend from the same terror. And that makes for the true magic:

It doesn’t give you the literal experience. It gives you what you really wanted: you feel the way the original made you feel.

So when I say Ringu is the best Junji Ito film ever made, I don’t mean it literally, any more than I mean it’s literally an M.R. James adaptation. I doubt Hideo Nakata was unaware of Ito’s work, but whatever their relationship, it’s safe to say that their works are, at least, spiritual siblings.

You can see examples of this kinship all over the place. They aren’t common, but they definitely happen.

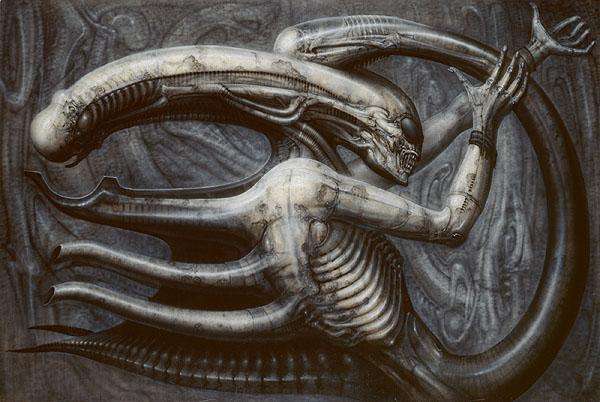

‘Alien is the best adaptation Lovecraft never got,’ is another example: what actual Lovecraft adaptation creates such a sense of an overwhelmingly vast, coldly hostile universe in which you can encounter horrors whose sheer physical presence breaks down the doors in your mind between the unbearably taboo and the inescapably real?

And while we’re at it, I’ll have a fair go at arguing that Jaws (1975), while also an adaptation of its own book, is a pretty good adaptation of Moby-Dick – I mean, Robert Shaw’s laconic, ‘When he comes at you, doesn’t seem to be livin’ – until he bites you,’ is a solid translation of Melville’s rococo prose into the picture-is-worth-a-thousand-words succinctness of a movie script, especially when you couple it with his magnificent performance. Shaw famously improvised part of that speech, and he was a novelist as well as an actor. He knew the ropes of this craft.

Feel free to skeet me your own examples. Sometimes the best way is to get into the spirit of things and go with that.

I hope I’ve made the case that talking about Ringu beside Uzumaki isn’t just bringing in a better movie, but a relevant one.

So let’s talk about it.

Ringu frightened me so much that the first time I saw it, I had to sleep with the radio on because I kept sitting bolt-upright in bed, certain that something was going to get me if I saw a curtain waver. Heck, my husband can probably thank it for something: one of the thoughts I had lying there that night was, I’d better keep my eye out for a nice boy, because it’s possible I can never sleep alone again.

Admittedly I had the curious good luck of having actually taped it off the air in the middle of the night onto a video cassette to watch later. That’s practically guaranteed to kill you.

So: there’s a cursed videotape that kills anyone who watches it seven exact days later – kills them untouched, it seems, except for a look of terror on their faces. A nice journalist-cum- single-mother, whose ex-husband seems to have some obscure and minor psychic abilities, starts to investigate it.

She assumes at first it’s an urban legend. Then she discovers her niece – who died suddenly, a healthy teenage girl, heart stopped and face contorted in fear – is supposed to have watched it.

So she starts investigating more seriously.

She really shouldn’t have done that.

Seven days of life between watching the peculiar but not overtly threatening videotape she finds, and . . . something happening. Something.

You are free to laugh at me that eight days after I watched it, I breathed a small sigh of relief.

How does this connect to Ito?

In terms of the monster, there’s a difference. Ringu’s monster stalks you, coming in from outside if you were foolish enough to invite it in. Ito’s are cancerous: something goes wrong inside you and then it grows.

But what they do have in common is pacing – that slow, steady, inescapable creep.

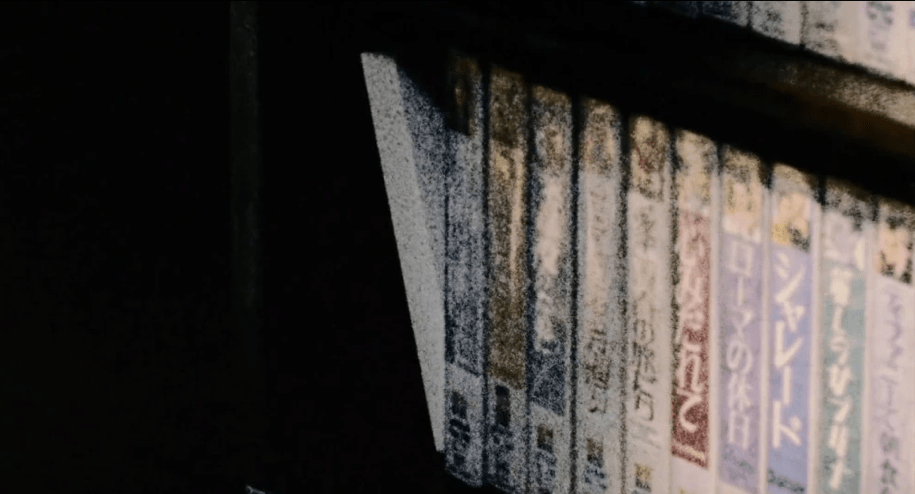

The horror becomes all-embracing, but it starts nothing worse than odd. Uzumaki begins with weird little coils – literally, the town just seems strangely prone to whirling micro-weathers. Ringu’s notorious cursed video tape isn’t very threatening when you first watch it.

Out of interest I looked it up, because you can spell it different ways with kanji for different meanings; this kanji indicates it means ‘chaste child’, so ‘Chastity’ is perhaps the closest equivalent, or if you’re going for the feeling of ordinariness perhaps something like ‘Blanche’ would be a better translation. Eerie, but more puzzling than dangerous. [End caption]

As in Uzumaki, so in Ringu: something is terribly wrong somewhere, but it’s just there – unseen, omnipresent, omnipotent. You can’t grasp it . . . but one day it’ll grasp you.

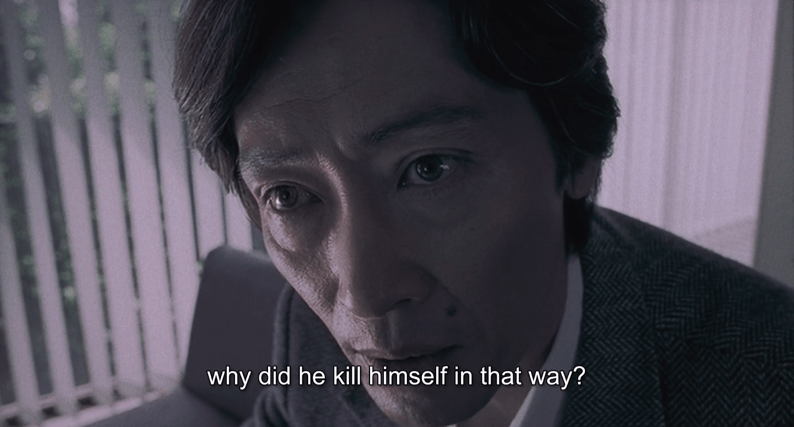

What causes all this, the heroine of Ringu asks her ex-husband? How did this start? ‘This kind of thing,’ he says bitterly, ‘it doesn’t start by one person telling a story. It’s more like everyone’s fear just takes on a life of its own . . . or maybe it isn’t our fear. Maybe it’s what we secretly hope is true.’

Death, in Ringu, is an act of will – the will of someone or something inhuman, implacable and relentless, that wipes out your own will to survive and records nothing upon your body but the fear you died in.

This is very close in spirit to the gathering obsessiveness of Junji Ito.

Ringu’s deaths are a lot neater. That’s one reason they work so well on film, in fact: much of the violence is internal, injuries inflicted psychically. Soundtrack and dramatic performance are just the way to convey that; a graphic novel of Ringu would be a much weaker work. But they share the same essential quality: the time is coming when you will be, somehow, overwritten.

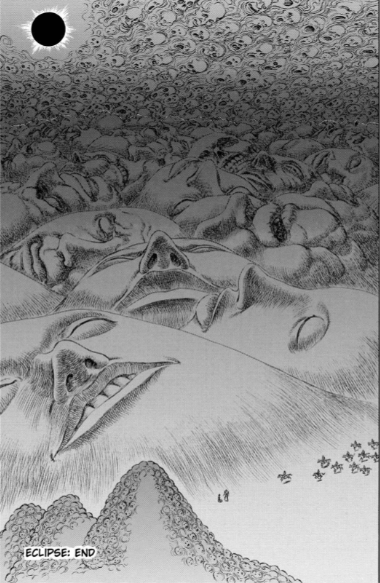

In Uzumaki it’s the spiral that’s a force of death – or transfiguration, a change of self so profound that whatever’s left alive it’s certainly no longer anything that could still be called ‘you’.

The only way your personality matters at all is in the kind of death that consumes you. A potter becomes obsessed with spirals in his clay. The school slowpoke degenerates into a curl-backed snail. A teenage girl determined to draw the attention of boys becomes a literal vortex.

What you wish for creates an opening for the spiral to twist into, perhaps. But in the end, that only affects how you go.

There’s no escape in Uzumaki. You die the way you lived, and the best anyone can hope for is a good end.

Every horror writer has their particular tale.

James’s is ‘I diverged from my regular research and it got too real.’ Lovecraft’s, I have joked with neurodivergent friends, is ‘I had to meet too many strangers and then I had a meltdown.’ (I can’t diagnose the man through the mists of history, but believe me, if you look at his stories through that lens they make so much sense. Certainly the feeling of an overwhelming universe populated by uncaring monsters, coupled with a terrible fear of emotional dysregulation and an uncertainty about your own relationship to humanity, rings bells among the ND people I know.)

Junji Ito’s is this:

I got a bad idea stuck in my head.

Yes, he rings the changes somewhat, but that’s Ito’s core terror. You get a bad idea stuck in your head, and it metastasizes. It calcifies. It eats you up, mutating you physically and spiritually, until there’s nothing left of you and only the idea remains.

Ringu is the closest we get, but there’s one thing it isn’t: it isn’t physical. Its deaths don’t twist up its victims; it’s better to say that they’re wiped out. Death is a force of negation, of nothingness imposed from an unseen place. But in Junji Ito death is vibrant, rampant, riotously visible.

So how do you film that?

Enter the live-action Uzumaki. It didn’t have the freedom of the fraternal resemblance; it had a story that it had to put onto the screen – and leaving aside the impossibility of Ito’s line, there were several serious difficulties that would have hobbled any project.

First is that the director was inexperienced.

Higuchinsky was a first-timer in movies and has directed very little since. For a film like this, at least if you wanted a good result, you’d expect to seek out a veteran horror auteur, give them plenty of time to get good and obsessed with the material, and expect it to play as an alchemical reaction between a great writer and a great director with the director adding plenty of his own flavour.

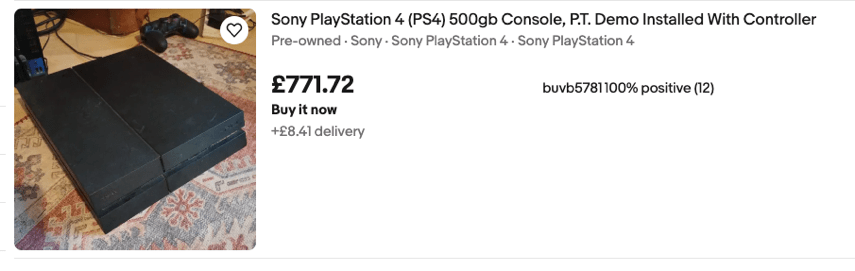

(This, incidentally, is why if you want to play the short video game PT you’d better have hundreds of quid burning a hole in your pocket. In 2014 Playstation released a free demo known only as ‘Playable Trailer’ – hence ‘PT’ – and there’s probably nothing in the world that has ever made horror gamers angrier than the fact that the intended game it trailed was never made.

It was a collaboration between Junji Ito, Hideo Kojima – the designer responsible for the Metal Gear franchise and the father of the stealth game – and Guillermo del Toro, who I assume needs no introduction here. You can watch a walkthrough of PT on YouTube, but if you want to play it you have to buy an old Playstation console with the original demo downloaded, and boy do resellers know how much people are willing to stump up for them.)

This movie didn’t have any of that. It had a director around thirty years old, who’d never directed a film and may or may not have had a bit of TV experience depending on whether you believe Wikipedia or IMDB, and if it’s that difficult to find out about him that tells you something about the track record he could bring to the project.

Second is that this movie was filming an uncompleted story.

That’s right: Ito hadn’t finished the book when they got started.

Details on the production have proved hard to find; what I’ve got is from Wikipedia quoting Twisted Visions: Interviews With Cult Horror Filmmakers by Matthew Edwards, but I haven’t read the book because it’s expensive, so take all this for what it’s worth.

From what I can gather (and thanks to Half Price Horror podcast for pointing this out to me) Higuchinsky was a fan of the original story as it was coming out. It was on that basis he pitched to make a movie adaptation – only to discover that it was already in production with Toei Animation and was in search of a director. It seems he had some TV experience so they took him on.

The international market must have been in mind because they were backed by Omega Project, which had previously had success releasing Audition (1999, Takashi Miike) – an altogether more poised and elegant creation with an old hand at the helm. If another Audition is what they were hoping for, this wasn’t how they were going to get it.

Higuchinsky told Edwards that he wanted to be as faithful to the story as possible – but how could he? He didn’t know how the story was going to end. And I doubt anyone could have seen it coming: Uzumaki escalates to levels of apocalypse Lovecraft himself might find spectacular. It’s not unprecedented in manga, which has the advantage that every page is drawn to the same budget, but even by manga standards it’s a wild ending.

So how to end the story? Higuchinsky had to work on his best guess.

Except you can’t outguess Junji Ito. He will always be scarier than you.

Even if Higuchinsky had expected it to get that extreme there’s a limit to what he could have done on a million-dollar budget. He had what he had, which was an unfinished story set in a small town, and he had to go from there.

Higuchinsky faced an impossible challenge.

How could you do one of the greatest horror books ever written justice under those circumstances?

I’ll be candid: going in I expected the answer to be, ‘He fell flat on his face.’ Even before I knew he was filming an unfinished work I didn’t expect much. Certainly if you check out stills from the film it looks like you must expect to have your time wasted.

And certainly he didn’t capture the tone Junji Ito strikes. There’s no delicacy and very little menace. The sense of a universe out of kilter lacks scale. It’s kind of goofy.

And yet.

And yet somehow it was a nice surprise.

Don’t get me wrong: it’s not a good adaptation. I’m not 100% sure it’s even a good movie.

But it was much better than I expected – and it got better and better the more impossible a task it seemed to realise it was facing.

Okay, so, there are several things to get out of the way if we’re going to make such a statement.

First thing:

I’m not sure it really knows what to do with the whole spiral thing.

And yeah, for a movie called ‘Spiral’, that’s . . . an issue.

You don’t need to have read the ending to understand that spirals are going to matter – yet early on in the action I genuinely wondered whether the camera understood the difference between a spiral and a circle. That’s like trying to film Cujo using a Norwegian Forest Cat instead of a Saint Bernard.

So yeah. Considering how Ito uses little spiralling details in the corners of his pictures, I was expecting Higuchinsky’s camera to do something either with his sets or his tracking, and I started having a better time when I let go of that expectation.

Second thing:

There are pacing and tone issues.

This is a ninety-minute movie, and we were fully an hour in before I was sold.

And again, I don’t think that can be put down to filming an incomplete work. It’s possible Higuchinsky was filming as he went along and just hoping that at some stage Ito would point to a conclusion, but that would be amateurish even for a first-timer. It certainly feels like a script that didn’t go through enough redrafts, but let’s assume out of good will that they at least finished it before they started shooting.

If you compare its pacing to the brutally efficient Ringu, the difference is startling. Higuchinsky does not have a strong throughline.

Here’s how Ringu begins: a couple of endearing schoolgirls are swapping the tale of the videotape where a mysterious woman appears and tells you you will die in seven days. Then one of them reveals anxiously that she did, in fact, watch a strange tape seven days ago. Her friend turns her back, and . . .

. . . well, something happens. The TV turns on by itself. Nasty little scraping noises tickle the back of your neck. The camera tracks forward, slowly closing in on the girl from behind.

She turns. She gasps. The screen freezes, bleaching to black and white.

It’s all quiet, and creepy, and as poised as a throwing knife, and you are not going to stop being scared after this.

Uzumaki opens with a bleeding corpse centre-screen; when we find out who it is he’s actually a minor character who has little to do with the action.

So much time is wasted on inconsequential moments of daily life. Scenes of Kirie going from undramatic place to undramatic place go on and on; there’s a sequence of tender shots of her riding the back of her boyfriend’s bike that take up so much time you’d be forgiven for thinking this was a love story.

And this points to a set of decisions Higuchinsky had to take: what was he going to prioritise?

Ito tells a tale of terror, and Kirie serves a very definite function within that: she is the witness. The sane person who sees others go crazy and holds out the longest. The straight man.

Her boyfriend Shuichi, meanwhile, is the prophet of doom who spots how things are going to go before anyone else. They’re the only two people, one normal and one foresightful, keeping their heads while all about them are literally losing theirs. And because there’s two of them they can talk to each other about it and we can listen in.

Their relationship gets almost no attention. They are each others’ confidantes; they have each others’ backs. That’s all you need to know. They’re high school sweethearts, but for all the play their romance sees they might have been married for decades.

Could Higuchinsky have known that? Well, yes. It’s in the text from the get-go, but you can also get the same message loud and clear from Ito’s other works. Charitably Higuchinsky might have over-interpreted Ito’s earlier Tomie series: in this collection a beautiful young woman draws the obsession of a new man every episode and ends up being killed by him, only to revive and obsess another – but Tomie is obviously some kind of psychological succubus rather than a romantic figure, and Ito had published plenty of one-shots by then too, and in all his work it’s clear that the scares matter more than the smooches. (Look, here’s a complete list! https://www.cbr.com/junji-ito-complete-works-guide/)

So the fact that Higuchinsky spends many precious seconds of screentime creating backstory about how long Kirie and Shuichi have known each other, about whether they’re officially dating, about what they plan to do after school . . . we have to consider that a directorial decision rather than prompted by anything in Ito’s work.

Unfaithful? In spirit, yes. But on practical terms it makes a certain amount of sense. It’s one of the few situations in the story that remains consistent and, however it was going to end, was clearly going to remain important. Sometimes you have to work with what you’ve got.

While he was at it, how was Higuchinsky going to shoot faces?

Ito is a master of expression, but the cast of this movie are – well, the best of them are competent, let’s say, and certainly they weren’t directed to deliver their subtlest work. And Higuchinsky’s decisions on how to film them are sometimes outright puzzling.

Sometimes we get flat mid-distance shots, and sometimes we get weird, uncomfortable close-ups. And it’s not always clear why.

Sometimes it’s about showing somebody’s going funny in the head, but sometimes the camera is just standing too close to somebody acting perfectly normal.

The tone feels, for a while, like something out of some Saturday-morning soap opera. It swings from flat to exaggerated in a way that, as long as the stakes are this low, plays as confusing.

And for a long time – almost two thirds of the movie – very little high-stakes happens.

So here’s the another issue to address in adapting Uzumaki:

You can’t shoot a film like a TV serial.

The original Uzumaki, being manga, was released in chapters. Each chapter acts as a kind of self-contained short story; especially in the early parts of the book, a particular character meets a particularly bizarre fate, affirming once again that Shuichi is right there’s something spirally about this town. Things build from there.

If this were episodic TV you could definitely do that. Fans nowadays are more used to bingeing shows than to the one-a-week format, so you might get some complaints, but it would preserve the original structure – and the original structure absolutely plays to Ito’s strengths. To the strengths of the horror genre as a whole, even; many of the scariest pieces of work ever written have been short, sharp shocks, and movies themselves aren’t that long.

But you’ve got ninety minutes to fill here and you can’t just shoot chapters one at a time. That’s not a movie – and in this case, with no final chapter available, it would eventually run you off a narrative cliff. Choices will have to be made.

It’s here Higuchinsky starts making decisions to deviate from Ito – and it’s here he starts to get interesting.

I don’t just mean that he had to guess the ending. What he did was re-order events somewhat and work towards a conclusion. He takes the natural path: have an A-plot with the central characters, Kirie and Shuichi, and pick several B-plot characters from individual chapters and weave them in and out of that.

Of course this fact doesn’t account for the inordinate amount of time spent on the cute slice-of-life parts that dominate the first hour. For about sixty minutes I genuinely wondered if Higuchinsky was interested in directing horror at all.

But the choice to build it around a normal young couple surrounded by increasing craziness from their neighbours, until finally the craziness catches up to them too – that’s perfectly sensible. He just spends much too long on the normal parts.

But while it does take too long to, well, spiral into horror . . . once it finally gets there, it becomes surprisingly effective.

This film takes a while to find its genre.

To begin with we feel lost in a kind of hazy, pink-skied drama with occasional forays into weirdness. But an hour in, the stuff that happened to Kirie and Shuichi’s families in the first two chapters of the manga starts to happen on screen.

And suddenly we’re watching a perfectly decent J-horror.

More than that, we’re seeing it find its feet – and it’s not where Junji Ito planted his. But that’s okay because it actually works.

The best compliment you can give this film is that it’s dreamlike.

There are ways in which it doesn’t land. It’s slackly plotted in some places and hasty in others. It has a weird understanding of when to shoot someone in close-up and when to film plain.

But this does mean that it keeps you disorientated. So when really grotesque things start happening – and in the final half hour they start happening bang, bang, bang, one after another – you’re off your guard.

Suddenly we get gruesome shots and startling cuts and upsetting moments, and it feels properly horrifying.

Nightmarish, we might say.

It’s not necessary to ramble in order to feel nightmarish, of course, but moments that leave you queasy or startle you do a lot to compensate for the baggier bits.

It feels like this film might have turned out properly good if it had just had better editing throughout – at the scripting stage, at the moment-to-moment stage in scenes, and in the big picture where decisions were made as to how much weight to give different elements of the tone and plot.

Somewhere in here is a film that starts with cute low-key domestic scenes, creeps in with minor worries and annoyances, then escalates to full horror and does a decent job of it.

And weirdly, Higuchinsky finds his best self when he tries to guess an Ito ending and guesses absolutely wrong.

I know. Normally I err on the side of purism, and I’m ride-or-die a fan of Ito. But still, bear with me on this.

Here’s the point: for the wobbly first hour, the adaptation keeps almost making aesthetic decisions and then forgetting about them.

For instance, there’s a moment where we have a screenwipe . . . and not only is it not a spiral when the chance was right there, it’s accompanied by a comedy sound-effect that would have sounded too doofy for an old Adam West Batman episode. It’s completely unmotivated, happening between one mundane scene and another, and it isn’t something that happens regularly enough to explain itself.

It’s a weird moment. It’s definitely a decision of some kind, but it’s hard to tell what got decided.

Or another example: Shuichi’s father, obsessed with spirals, goes to commission a piece from Kirie’s father, a potter not yet obsessed with spirals. We don’t see this happen in the manga, we just hear Kirie mention it, but Higuchinsky films it – and he makes a good decision. Shuichi’s obsessed father brings a camcorder, zooming in on the clay as Kirie’s father shapes it on the wheel.

This was a year after The Blair Witch Project (1999), so diegetic footage was still quite a new and clever idea. There are scenes later where it’s used again in the form of TV-station news of weird events, a smart choice to cover up the limitations of whatever special effects they could scrape up. More could have been done with it – the shot I included above is as close as we get to the possibilities of showing two experiences on screen at once.

But it’s an artistic choice. Just one that we don’t see as much of as we might: you’d think a camcorder in the hands of a spiral nut would be a brilliant filmic opportunity, but it’s one only slightly taken.

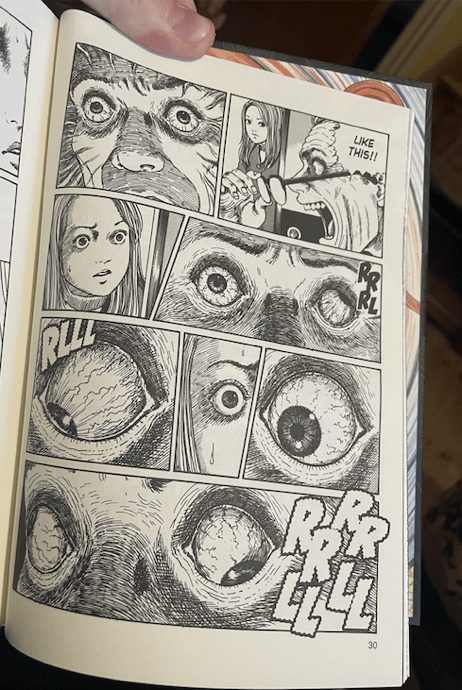

Or yet another example: Shuichi’s dad, mid-craze, starts rotating his eyes in spirals. Obviously a film can’t reproduce the combination of wild extremity and subtle linework, manic glee and buried anguish that Ito gave this moment – but the interesting thing is that it doesn’t try.

Higuchinsky went in a completely different direction. He used camera distortion to produce an effect that’s almost cartoonish. Not manga, but comic-book.

Farcical.

And in the last half-hour, that’s where the film suddenly finds its footing.

For an hour we’ve been lolloping about with lulls of nothing-in-particular and scares building far too slow. But now the whole place is going batshit and there’s shock after shock, and lo and behold, it’s a fun horror movie.

And the interesting thing is that this is where it properly diverged from Ito – not just tonally, but in narrative.

Higuchinsky’s ending is stupid and I like it.

The horror at the end of the manga is Lovecraftian in the best sense: we see human lives destroyed not out of malice, but by a universe so vast that it’s entirely impersonal. Whatever the spiral is, it doesn’t have any kind of thought process as a human would understand it. It’s a figure of geometry. Judging it makes about as much sense as an ant judging the crushing foot that didn’t see it there: this isn’t about intent, it’s about magnitude.

Higuchinsky introduces a journalist who does a bit of research and discovers that the town used to be occupied by a snake cult.

That’s right: a snake cult. And if you want more detail, we are sorry to inform you that the journalist dies in a car crash before he can tell us any.

I don’t know the exact process by which Higuchinsky arrived at this decision. Maybe it was his best guess – which would go to prove my point that you can’t guess Junji Ito’s endings because they’re always worse than you think. Maybe he intuitively understood that the reasons for the spiral don’t really matter, but didn’t quite have Ito’s chops to make that a feature of how terrifying it is – and so instead he created this kind of homework-excuse of an explanation: Does it even matter? A cult did it and ran away, now leave me alone.

This is not like Ito’s book – but interestingly, it is like Ringu.

Ringu too rests on a relatively small piece of local folklore as the source of all the trouble.

‘A psychic woman gazed too long into the haunted sea.’ ‘A snake cult took over the local pond.’ They’re not unlike, are they? And as narrative explanations for weird goings-on, they’re perfectly adequate if you can just sell them to the audience.

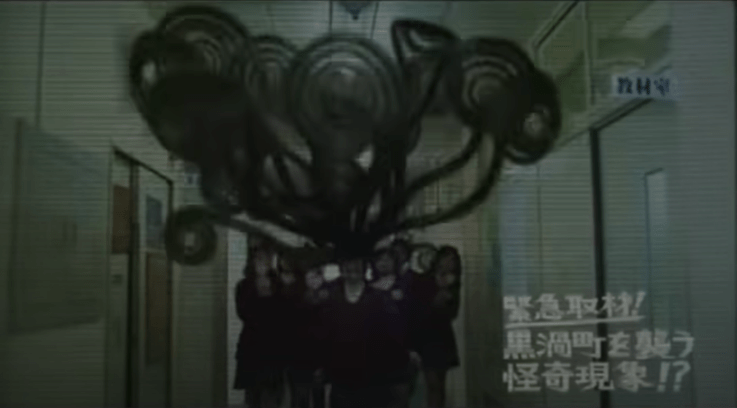

At the point where Higuchinsky goes full Ringu, the film has a brief moment of narrative clarity – and it’s reflected in the visuals. The plain grey library in which the journalist researches snake cults looks a lot like the plain grey offices in which our journalist heroine researches in Ringu; the shots Uzumaki shows around the journalist’s revelations look a lot like images from Ringu’s cursed video tape.

Research happens in plain-looking offices and libraries. Discoveries fill the screen with foreboding kanji and grainy shots of historical disasters.

And yeah, it’s not exactly original. Neither does it have any of Ringu’s poise: Nakata had restraint, delicacy, precision and ferocity, charging his most inconsequential moments with a quietly fraught tension. I remember seeing brief glimpses of it the night I was taping it – I was watching something else and channel-flipping during the ad breaks – and even its innocuous moments gave me the willies.

This is entirely beyond Higuchinsky; whatever he intended for his tone, it came out zany – which is what tends to happen when you shoot for Gothic and miss.

But zany storytelling has its own charm once it starts clicking.

If there’s anything Higuchinsky learned from Ringu it was, eventually, to get on with the story. Petrifying delicacy? No. A lively pace? Finally, at the one-hour mark: yes.

And the fact that it’s tonally goofy long ago stopped mattering.

Does a snake cult explain why the town is going spiral-crazy? Well, not exactly – but I’d say it explains it about as much as you need it to if all you want is some kind of placeholder in your head that lets you feel there’s some reason and get on with enjoying the scares.

It was the wrong guess. It’s a lot dafter than ‘the universe is just a strange and uncaring place’.

But that’s a good thing. Because Higuchinsky’s camera has been daft all along, and now he’s finally found a way to tell the story that matches it.

Here’s where I found the right comparison for the film Uzumaki.

It’s not Ringu, or Ju-On, and it’s definitely not anything by Junji Ito. It’s a 1977 cult horror comedy by Nobuhiko Obayashi called House.

House is better than the film Uzumaki, no question. There’s an edition of House done by the Criterion collection because it’s a classic of its kind, which is to say ‘one of a kind’: there aren’t many films like this in the world because few people can sustain that level of frenzy for very long.

It’s wildly silly up to heights Higuchinsky didn’t reach. But it’s a good comparison because it tells us what genre we are in: horror farce.

[Caption]

Horror farce is a fairly small genre, but it’s there; just a year later in 2001 there was the horror-farce-musical The Happiness Of The Katakuris, and no less a director than Takashi Miike did that. This, I think, is where we find the film Uzumaki’s real kin.

It doesn’t entirely hit those high notes. But an explanation as pulpy as a serpent cult is pretty good, and the weird screen-wipes and comedy sound-effects and dream-moments where the imagery goes almost full cartoon certainly fit more comfortably into the territory of farce than anything else.

And Higuchinsky goes at it with enough gusto that I don’t think we can call it accidental. Or if it was accidental, it went hard enough that it landed in the realm of pure camp.

There’s an old Japanese folktale usually called ‘The Faceless Ghost’ or ‘Mujina.’ A traveller after dark runs into a horrible something, and things get worse from there. I won’t spoil it because it’s probably the most horror-movie of all the Japanese spook tales I know (which mostly means those collected in Lafcadio Hearn’s Kwaidan), but it’s a proper campfire tale that’ll give you the creeps.

But this is an important part of the tale: the monster isn’t actually a threat. It’s a tanuki – what sometimes gets called a ‘Japanese racoon-dog’. That’s a real animal, a fox-like canid that in folklore is capable of becoming a wily shapeshifter as it gets older. And sometimes they like to play pranks on humans.

Photo by Stanislav Duben

I first heard the story by candlelight, crooned by the Japanese mother of a friend of mine, and it properly made my skin crawl – but what happens to our poor traveller in the story doesn’t happen because something really dangerous is after him. It happens because a tanuki has its own ideas of the hilarious.

And I think that’s what happened to Uzumaki.

Sometimes the director is a monster – and sometimes he’s a tanuki.

It’s possible Higuchinsky went into it with a sense of comedy, or it’s possible the project twisted him into a tanuki as he went along – in which case, well, that’s what Ito does to you. You never come out of his stories the same as you went in.

But once I realised I wasn’t getting cosmic catastrophe and accepted that I was travelling through the realms of grotesque comedy, things cheered right up. For an hour I was every bit as unimpressed as I expected to be, and then suddenly I found I was having a good time.

And you know, that’s not against the spirit of Junji Ito. The man has a sense of humour.

Certainly in the manga Uzumaki the darkly grotesque has more of an emphasis on the ‘dark’ part of that equation, but I don’t think anyone can do horror as well as Ito if they don’t understand the ridiculous. The scare and the laugh are bedfellows: you need a fine sense of the line between them so you can stay on the right side of it. A really skilled writer like Ito can dance back and forth, lowering your guard with the wacky and then jolting you into the deadly. Shuichi’s father’s madness is almost uproarious until it bloodily isn’t.

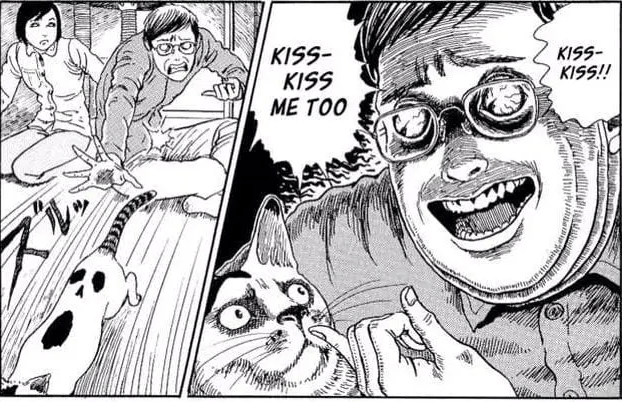

And Ito wasn’t above poking fun at himself. One of his best-liked minor works is Yon and Mu, a story in which he parodies himself as the hysterically neurotic owner of two perfectly normal cats. One of them happens to have a pattern on its back that looks a little like a deaths-head, and the fictional Ito goes weird over that.

Of course it has its groteseque visuals – it is a Junji Ito work, after all – but it’s farce and it’s himself he’s making look silly, because he’s far too good a writer not to know that there’s something ludicrous about all of this, and that that can be scary too. A laugh might be close to a scream.

So Higuchinsky’s infidelity to Junji Ito – his wrong guess or his deliberate choice, it hardly matters to the finished project – turns out to be the best decision he could have made.

He didn’t really film a Junji Ito story – but that’s okay: you can’t film a Junji Ito story.

And you’re better off if you accept that. You can make something inspired by Junji Ito: his mood and aesthetic are there for the taking. You can make a film like Ringu that’s equally good and hits you in the same weak points. But trying to be dead faithful will only ever get you the-same-but-worse.

This movie is better in the moments where it doesn’t try.

And that really is a nice thing to find out. I’ll admit it: I was cynical when I approached this project. I thought the film itself would be nothing to write home about, so to speak – that there’d be little to say except, ‘See? Unadaptable! Spiritual adaptations are the only way to go!’

I stand by that. But what I also discovered is that there’s another way to not adapt something – and in its way it’s also a spiritual adaptation. It’s to let yourself become the victim.

It’s in the spirit of the impossibility of the whole business.

Who could adapt Junji Ito properly? Nobody. Maybe some future technology will have the processing power, but at the moment it’s like trying to play an orchestral symphony on a xylophone.

But there’s nothing wrong with a xylophone as long as you use it to play xylophone music.

Higuchinsky didn’t make a cosmic horror film. He made a farce: tonally all over the place, goofy, schlocky, highly stylised. And the more I think about it, the more I respect that. Not with the part of me that likes Junji Ito – but that part of me already has Junji Ito. I like it with the part of me that likes pure creative energy.

Sometimes the best adaptation is a transfiguration.

You want to feel the way Ito makes you feel, or M.R. James makes you feel? Watch Hideo Nakata. You want to feel the way Lovecraft makes you feel? Read Junji Ito or watch Ridley Scott.

You want to feel what it’s like going loopy in the face of the impossible?

Imagine you had to adapt Junji Ito, and then watch Higuchinsky’s Uzumaki.

It won’t put you in the position of one of Ito’s fictional victims – but it will for sure give you a maniacal cackle. And that’s part of Junji Ito too.

You don’t watch this movie as an Ito victim. You watch it as an Ito nutcase.

And why not? Ito’s story is, ‘I got a bad idea stuck in my head.’

‘I can adapt Junji Ito!’ is a very bad idea.

You can’t do an adaptation of Junji Ito that’s both faithful and good: the idea is farcical. Like an inexorable Ito monster, the foolishness of your mission will eventually twist through every fibre of your project.

So why not embrace your doom, submit to the inevitable, and spiral into the ridiculous?

In the end, that’s a very Uzumaki thing to do.

. . . And that concludes our fun for this episode. I’m off to go turn in circles now. It seems necessary somehow.

Check out more of Kit’s amazing essays here in our What’s on Shudder Column.

Spiral into a great book! Buy my fiction! It’s a great price on Kindle!

The Gyrford

Everyone knows that if you fall afoul of the People, you must travel the miles to Gyrford, where uncounted generations of fairy-smiths have protected the county with cold iron, good counsel and unvarnished opinions about your common sense.

But shielding the weak from the strong can make enemies. Ephraim Brady has money and power, and the bitter will to hurt those who cross him. And if he can’t touch elder farrier Jedediah Smith, he can harm those the Smiths care about.

The Smiths care about Tobias Ware, born on a night when the blazing fey dog Black Hal roared past the Wares’ gate. Tobias doesn’t understand the language or laws of men, and he can’t keep away from the Bellame woods, where trespass is a hanging offence. If Toby is to survive, he needs protection.

It should be a manageable job. Jedediah Smith has a head on his shoulders, and so too (mostly) does his son Matthew. Only Matthew’s son John has turned out a little . . . uncommon. But he means well.

It wasn’t his fault the bramble bush put on a berry-head and started taking offence. Or that Tobias upset it. But John’s not yet learned that if you follow the things other folk don’t see, they might drag those you love into the path of ruin.

Further Reading

Horror movie fans looking to deepen their appreciation for the genre should definitely check out the Horror Movie Review section of Ginger Nuts of Horror. This platform is a treasure trove of insights, critiques, and discussions that resonate with both casual viewers and dedicated aficionados alike.

Firstly, the reviews are penned by passionate writers who understand the intricacies of horror filmmaking. They delve deep into the elements that make each film unique, from unsettling visuals to compelling sound design, offering a comprehensive analysis that goes beyond superficial impressions. Such in-depth reviews can enhance viewers’ understanding and appreciation of the genre, revealing layers of meaning and intention that may go unnoticed during a first watch.

Lastly, with its focus on both mainstream and indie films, the Horror Movie Review section is an excellent resource to stay updated on upcoming releases and trends in the horror landscape. For any horror buff, exploring The Ginger Nuts of Horror Review Website is an essential step toward a deeper connection with the genre.