What We Don’t Talk About When We Make Films About Trans Killers

Psycho, A Woman Kills, Dressed To Kill, The Silence of the Lambs – and conversely, Satranic Panic and I Saw The TV Glow.

A note on language. I’m going to be using the word ‘queer’ as a catch-all for LGBTQ+; I’m aware that this is a reclaimed slur that not everybody likes. I’m also aware that as a cishet person, it’s not my term to reclaim, and if it wasn’t already in use by many LGBTQ+ people I wouldn’t be using it.

I don’t want to say LGBTQ+ every time because it’s a list that doesn’t describe individual characters; I don’t want to say ‘non-cishet’ because that centres the people I’m not talking about. My understanding is that the word ‘queer’ now denotes people who are not only non-cishet but who advocate for LGBTQ+ rights – that is, it’s a term of political solidarity as well as sexuality/gender, and that’s the spirit I hope to use it in.

I also want to note that gender (who you are) and orientation (who you’re attracted to) are not the same thing: any kind of person can be into any other kind of person. I’ll do my best to keep this clear when talking about these movies; at some points that’ll be more difficult than others because some of these movies were made by people who either don’t know or don’t care to tell the difference. If I seem to conflate gender or orientation myself at any point, that’s bad writing on my part and not an intention to actually class them as interchangeable. I’m using ‘queer’ on the understanding that bigotry is despicable, queerness beautiful and solidarity vital.

I’ll also have to quote the word ‘transexual’ in film dialogue, which I’m aware is not the term preferred today.

Unsurprisingly this essay will talk about transphobia and violence, so you know best whether it’s a subject you feel up to today. Be nice to yourself.

Welp, it’s that time of the year again: Ryan Murphy and Ian Brennan just unleashed another season of Monster on the world, and this time it’s about Ed Gein. Or rather, it’s about a hot young queer-coded man who commits violent acts, because that’s what Monster is always about. I don’t know what it is with this hybristophilia lark – that is, thinking violent people are hot – but I wish someone would make a series about that instead.

Monster is not really about Ed Gein at all. But you do get to see a man in lingerie – though if that’s your thing I’m sure the Internet can provide you with plenty of lovely examples without having to watch something that suggests Anthony Perkins was an Ed Gein fetishist. The poor guy suffered enough in his life.

Ed Gein wasn’t trans, for the record. He wasn’t gender-nonconforming or queer in any way. When his crimes came out newspapers frothed up a whole lot of speculation that he must be, because the idea of a cishet man doing anything so wildly grotesque was one of those things mid-20th century America found pretty much outside the realms of possible thought. Gein was a cis straight man who was severely mentally ill, and the fact that he became such an ‘inspirational’ figure in horror fiction has a lot to do with fictions created about him that were reported as facts.

Sometimes there’s an archetype just looking for a person to fill it – and sometimes in the year 2025, a whole lifetime later, apparently it still can’t just go in the bin where it belongs.

Are we doomed to this archetype, or is there hope?

A woman is alone, vulnerable. Maybe showing a bit of skin.

Up behind her creeps a figure. It wears a dress. A wig. It’s a woman! No, it’s a man! Agh! Run! Shoot! Change the laws about bathrooms! Take away medical care from children!

We all know this story. But does it have to be this way? What about horror that treats gender nonconforming people not as a boogeyman, but as people to rejoice in?

It’s not a nice time to be trans right now. I don’t speak for trans, non-binary or otherwise gender nonconforming people, but I love that they exist. Trans, non-binary and GNC people being who they are is excellent, and it seems worth it to say that in public.

Where do we start?

Shudder has some excellent films at the moment, but I’d been having a smash-and-grab and had written about all the ones that really interested me. So I was trying this and that, and I came across what seemed to be an obscure French New Wave film. Why not?

Except it turned out to be an example of the ugly old ‘man-in-a-dress kills beautiful women’ story that seems to underly a lot of transphobic myths.

So I went and watched another movie by trans creators, and you know, that really cheered me up. Which got me wondering:

How many ways are there to do the trans-killer trope? And is there any way to fight it?

In this essay we’re going to talk about some of the classics of the anti-trans horror staple, including the obscure one I found on Shudder, to wit:

Psycho, 1960

A Woman Kills, 1968

Dressed To Kill, 1980

The Silence of the Lambs, 1991

Then we’re going to talk about some horror by trans creators by way of refreshing our spirits:

Satranic Panic, 2024

I Saw The TV Glow, 2024

To be clear, trans and gender nonconforming people make art in every era, so I’m not saying these are the first movies of their kind. I’m just covering the only one I could find on Shudder (Satranic Panic), and a companion piece that’s deservedly getting a lot of attention (I Saw The TV Glow). If anyone wants to recommend older horror movies by trans creators then do drop a comment on Bluesky either for me @kitwhitfield.bsky.social, or Ginger Nuts @gnofhorror.com. Anything that gives trans creators a boost sparks joy with us. Let’s promote and celebrate!

A final disclaimer: I can’t speak about queerness in films from an inside perspective. That’s why I feel the need to explain what got me writing about this; it’s not because I’m any kind of expert. I am as straight and gender-conforming they come: a zero on the Kinsey scale who entirely identifies with the gender she was assigned at birth. I’m the exact kind of person the scary-man-in-a-dress trope is supposed to put into a panic.

Except, of course, I’ve got the sense I was born with and it doesn’t. What I actually found, looking at these various films I’m going to discuss, is that the more a movie assumes I’ll automatically be scared of a man in a dress, the more contempt it also has for women. Theydies and gentlethem, we have a common enemy here. I didn’t need to know that to be on trans people’s side in this, but it certainly was a finding.

I won’t rehash the history of trans stereotyping in cinema here; there’s an hour-long video essay by Lindsay Ellis I’d recommend on the subject that I’d highly recommend: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=cHTMidTLO60. The short version is that you can trace a line of descent from Psycho through Dressed To Kill and The Silence of the Lambs and beyond, all resting on a simple premise: when a man kills women, it isn’t his masculinity to blame. It’s because he’s a failed attempt at a woman.

Let’s take a look at this bewigged monster of cinema and see what it has to say for itself. Some of it will be depressing, but there’s better things out there as well, things in dialogue with the false horror that know where the true horror lies.

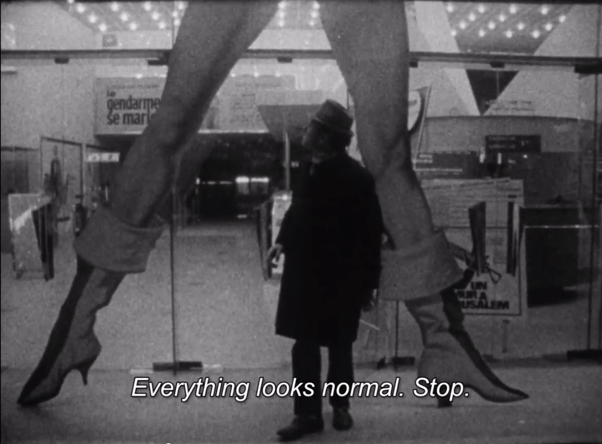

We’ll start with the 1968 French New Wave thriller A Woman Kills, directed by Jean-Denis Bonan.

Because that’s where I started, and I bet you haven’t heard of it either. But it’s interesting – not least because of what it assumes goes without saying.

If you aren’t familiar with New Wave cinema, the movement was a rebellion against its more formally plotted, visually smooth and politically palatable forbears. Nouvelle Vague favoured a scrappy, quasi-documentary style, cobbling together what it could on small budgets, shooting stories in choppy and confrontational ways that left the viewer to react however he saw fit (and yes, it did tend to assume the viewer was a ‘he’). Rough, compelling, stylish, New Wave was hugely influential: it made a point of the ‘auteur’, the brilliant man who made movies for smart people.

Which can, at its best, make the experience of watching almost childlike. That’s a counter-intuitive thing to say considering how consciously grown-up New Wave cinema worked on being, but do you remember what it was like being a child? Everywhere you looked was new information, unprocessed and unexplained, a world of things just happening that you had to figure out your own conclusions from, which you could only do by close concentration. To see was to learn, continually.

At its best, that’s how A Woman Kills watches: matter-of-fact information presented so starkly that it takes on the incompleteness and fascination of a dream.

Unfortunately in 1968 that dreamlike quality opened the door to psychoanalysis, and with it, some truly stupid ideas about gender.

In short: this is a film that finally forced me to watch Brian de Palma’s Dressed To Kill by way of comparison, and I haven’t forgiven either of them.

Here’s the plot of A Woman Kills.

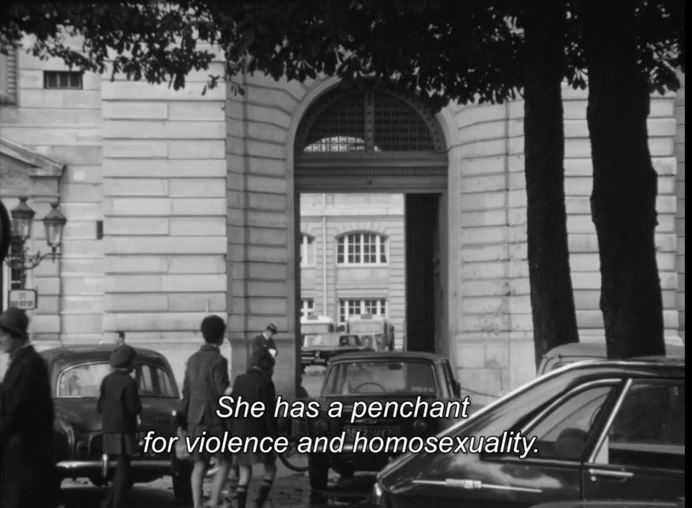

A woman called Hélène Picard has been executed for a series of murders, specifically sadistic killings of sex workers. She was ‘known for being a runaway, a thief and unstable’ with ‘a penchant for violence and homosexuality,’ so we can’t say we weren’t warned. This is the era determined that homosexuality was a mental illness, and it goes from there.

The story follows another sadist inspired by her murders to kill copycat-style: a civil servant called Louis Guilbeau, diagnosed with ‘slight paranoia’, but who’s actually up to much darker things.

The film is experimental with technique, and one of its interesting tricks is to deploy three different methods for conveying story.

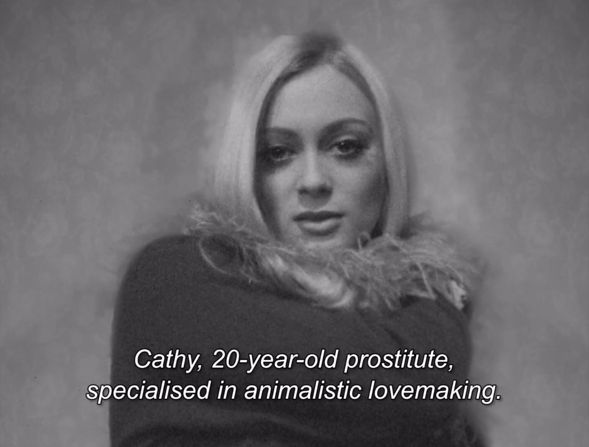

First, there’s a true-crime style voiceover in which it describes the victims, their life histories and the time and date of their deaths with the brisk impersonality of a police report.

The second approach is naturalistic scenes, handheld and rough as per the New Wave style, but often captivating in their framing, drawing you in by what they make difficult to see as much as by what they show. Mostly they follow Louis as he dates Solange, another government worker who will eventually discover his sinister secret, take part in a police chase, gun him down and get a medal for it. That’s the action-thriller part of the story.

His secret, by the way, is that he likes to dress in women’s clothes. Also that he’s a murderer, but the two are pretty much conflated.

The third is what you might call musical numbers. A warbling male voice sings commentary upon the action: the murders in Paris, the screams of the victims, the fate closing in on the murderer, documenting in song the awful things that are happening. New Wave used what it could find, and a didactic soundtrack was one of those things here.

It’s not one of the best films of the New Wave, and at points it grows so determined to maintain a cool detachment from the conventions of cinematic plotting that you start to wonder exactly why it’s showing you everything it’s showing, but it’s visually interesting and mixes in interesting and dramatic stuff.

But when it comes to queerness, its curiosity simply shuts down.

Why did Louis kill all those women? Well, after a genuinely thrilling pursuit through a derelict city including a rooftop chase, featuring shooting on all sides and the police chief instructing his men in graphic terms to draw blood and ‘Wear him out like an animal,’ Louis is cornered by Solange and gives his statement.

We’ve heard since the 15-minute mark that Louis’ mother would dress him as a little girl. Finally trapped, he declares, ‘My mother did this to me . . . I wasn’t given the chance to be a man . . . I was pushed to the abyss of vice.’

That’s the full explanation. That’s all the film needs to show us. Solange shoots him and a voice-over explains she will successfully claim self-defence, but diegetically it’s simple murder: he has a gun but he isn’t aiming it at her, only confiding his childhood trauma. The film affirms, as much as New Wave neutrality possibly can, that she did right to murder him. It’s a restoration of justice, the ‘animal’ destroyed, and destroyed in the most heteronormative of ways: Solange shoots ‘her boyfriend’, as the narrator calls him, and then later she gets married, presumably to someone manlier.

It’s important here that the French New Wave directors loved Alfred Hitchcock’s films.

I mean, who doesn’t? I can’t count the number of times I’ve seen Psycho, and if you offered, I’d watch it again with you right now.

But Psycho came out in 1960, eight years before this supposedly experimental, edgy work, and it lifts the ‘man driven to a life of cross-dressing murder by a domineering mother’ concept wholesale.

What do films do when they lift that concept?

What A Woman Kills took from Psycho was pure knock-off Freudianism. A castrating mother will produce a sexually dysfunctional son; serial killers are sexually dysfunctional; therefore, in a false syllogism that would make Aristotle weep into his beard, serial killers are created by castrating mothers.

The thing is, Psycho was actually quite careful to avoid making generalisations about gender nonconforming people. The concluding scene in which a dapper, impeccably masculine psychiatrist explains Norman Bates’s murders is written with an eye to keeping it specific and detailed:

Psychiatrist: He was already dangerously disturbed. Had been ever since his father died. His mother was a clinging, demanding woman, and for years the two of them had lived as if there was no one else in the world. Then she met a man, and it seemed to Norman that she threw him over for this man. Now that pushed him over the line and he killed them both. Matricide is probably the most unbearable crime of all; most unbearable to the son who commits it. So he had to erase the crime, at least in his own mind . . .

He was never all Norman, but he was often only mother. And because he was so pathologically jealous of her, he assumed she was as jealous of him, he assumed that she was as jealous as him. Therefore, if he felt a strong attraction to any other woman, the ‘mother’ side of him would go wild . . .

Sam (the murdered woman’s fiancé): Why was he dressed like that?

Cop: He’s a transvestite.

Psychiatrist: Ah, not exactly. A man who dresses in women’s clothing in order to achieve a sexual change or satisfaction is a transvestite. But in Norman’s case, he was simply doing everything possible to keep alive the illusion of his mother being alive.

Now, by modern psychiatric standards this is far from accurate. For starters it conflates being a transvestite with being transgender, two quite different things. It also perpetuated some ideas about ‘multiple personality disorder’, a misconception that led to both bad representations in fiction and instances of actual medical malpractice. To be clear, it’s now called Dissociative Identity Disorder, it’s nothing like it looks in the movies, and it’s not associated with violence.

However, Hitchcock’s script (written by Joseph Stefano and Robert Bloch) was at least trying to make it clear that Norman Bates was not, diegetically, either trans or a cross-dresser.

He isn’t even coded queer, which is the sort of thing a less skilled team in that era could easily get confused. Anthony Perkins himself was gay, and given the bigotry of the era he undoubtedly brought to the role a knowledge of what it means to have something about yourself that you need to hide. The poor man even went through conversion therapy in the 1970s, which of course didn’t make him straight, just traumatised. He understood the fear of discovery.

But however subtle Perkins’ performance – and it is a masterpiece – his personal life stayed well behind the camera. Given all the violence and Gothicism we might miss this, but it’s actually important: Norman Bates has no ‘abyss of vice’ to his desires.

What he does is bad, but what he desires is exactly the same as Marion’s boyfriend Sam. Both are cis men attracted to a conventionally beautiful woman their own age. But Sam is as close as the film gets to a hero, and in a way that fully embraces traditional 20th-century masculinity: an aspiring provider turned justice-seeker whose main motives are loyalty to his late father, duty to his financial responsibilities and romantic love for his fiancée. That’s an archetypical American good man – and his sexual desires are no different from Norman’s. When Norman’s not trying to delude himself out of guilt, he’s straightforwardly and traditionally male.

Unfortunately that’s not what stuck. A Woman Kills picked up the bare bones of the story and ignored the disclaimers.

What else does A Woman Kills not talk about?

Here’s one question it absolutely didn’t ask itself: is it that necessary to see women naked?

The New Wave was fairly typical of 60s cultural movements: cutting-edge, bohemian, daring, and very much a boys’ club. Agnes Varda was the only major female member, and tended to be neglected by film historians (https://ecufilmfestival.com/nouvelle-vague-agnes-varda-as-a-pioneer-of-feminism/). In a lot of New Wave, women were gorgeously filmed, but through an extremely male lens.

So it is in A Woman Kills. We see naked sex workers. We see action heroine and government employee Solange taking a bath, a naked civil servant. We see a scene where she poses on a bed for Louis four times in four different outfits, the same shot tracking up her body in the same pose time after lingering time until, being uninterested in lusting at girls myself, I heard myself exclaim aloud, ‘Okay, stop, please, I know what her legs look like!’

And to be clear, if you are a leg man, more power to you and I hope you see lots of legs belonging to people who enjoy your admiration. But while it’s a simple point to make, it can’t be missed that in demonising the unmasculine man, A Woman Kills also takes for granted that women should take their clothes off and be stared at.

It’s the corollary: non-normative masculinity is evil; normative masculinity is good, and therefore should be served plenty of treats while it watches this film.

Because one of the things that A Woman Kills doesn’t need to say, but which is hard to forget when we watch it, is that in 1968 pornography was difficult to get hold of.

Which brings us to Brian de Palma and Dressed To Kill.

Dressed To Kill (1980) has not aged well. It revolves around the same trope – a man in woman’s clothes murders attractive women – and it’s one of the most infamous when talking about transphobic movies. A Woman Kills is obscure, but Dressed To Kill is a classic of its kind. I didn’t feel I could talk about one without at least watching the other.

I did not enjoy it.

I promise we’ll end by talking about some good films featuring trans people, but Dressed To Kill is really painful.

Candidly, of course I wasn’t watching it with a charitable eye; I like trans people and I don’t like films that make them look evil. But even if I’d gone in with a more open mind, I don’t think my good will would have survived all the tits.

Sex scenes as well, but so, so many shots of tits.

Again, if you like to look at tits, good luck to you. Sexual love is beautiful and sexual pleasure is fun. But I’m a cishet woman who doesn’t like looking at tits at all, really, and having them shoved in my face when I’m trying to watch a movie makes it less fun for me, not more.

And in Dressed To Kill there is so much camera time spent on showers and baths. Now, of course de Palma is a famous fan of Hitchcock, and nobody can make a film with a woman showering without at least being aware of that scene.

But de Palma isn’t just ripping off Hitchcock; by this point he’s ripping off himself. Four years previously he began Carrie with a scene of a lovely young girl soaping up her every smooth limb, and here in 1980 he begins with the exact same scene. Angie Dickinson, fully-made up, takes a shower while lush music plays and the camera gazes and gazes at her various bits.

And it isn’t even plot-relevant! In Carrie something actually happens in the shower that kick-starts the story, but in Dressed To Kill? At the end of the scene someone comes up from nowhere, grabs and kills Kate, and then we jump straight into another scene where she’s alive. Was it a fantasy? A dream? De Palma, usually a very coherent director of action, does not make it clear. If you looked up ‘gratuitous’ in the dictionary there would be a picture of this scene.

It lasts a full minute. After a while I actually started fast-forwarding because it felt like I was intruding on a private moment between de Palma and his camera lens.

And we just go from there. Again, this is very much a film of the era where unless you were prepared to go into a seedy theatre or shop, porn was just difficult to get your hands on and you had to make do with whatever sauce the mainstream offered. Women read steamy romances; men watched movies like this. There’s nothing inherently wrong with either – we’d none of us be here if it wasn’t for orgasms – but when you’re also directing a film with a queer villain, it can have two bad effects.

First: it taps deep into the conflation of disgust and morality. At the end of the film, the very attractive Nancy Allen explains the physical details of hormone therapy, penectomy and vaginoplasty to an uncomfortable-looking Keith Gordon; her amusement and his disquiet are key to the scene. Narratively we don’t need to know all this, it’s pure prurient curiosity; the function it serves is to confirm that everything about the murderer – not just the murders, but the sexuality – is abnormal and disturbing.

And that lands harder because so much of the film has revolved around getting a good look at beautiful women, and casting those women as victims and heroines. If you’re into naked ladies, there’s a visceral force to who’s evil and who’s good in these movies: you can judge very simply by who’s yuck and who’s yum.

Which is not a good reaction to take into real life, where in fact many people can be outside your personal sexual tastes without being evil stab monsters.

The second problem is one of film-making. Hitchcock could be a horny old goat, no doubt about it, and was far from ethical about it personally, but his tastes lent themselves to good suspense films. There’s an interesting essay I’d recommend here about the ‘Hitchcock blonde’ – https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=EjSde5Su-14&t=2110s – but the short version is that Hitchcock very much favoured the reserved and enigmatic feminine with an implied passionate private side. A mysterious and secretive woman can do plenty in a thriller while remaining in perfect harmony with the needs of the plot. Those plots depend on mystery and secrets.

De Palma, though? His horny camera doesn’t sit well with his Hitchcock stylings.

Let’s do a bit of comparison.

In Psycho, our heroine, Marion Crane (Janet Leigh), is unexpectedly murdered at the end of the first act. We thought we were watching a thriller about a woman who succumbed to temptation and stole money from her employer so she could marry her impoverished boyfriend. On her way to him, she checks into a motel and is killed.

The fact that she robbed her employer leads to a detective being hired, who tracks down her last whereabouts, getting the rest of the plot moving as people move in on the Bates Motel. Everything she does before the murder is foundational to what happens after it.

In Dressed to Kill, Kate Miller is a sexually frustrated woman who gets laid. And that’s really all she does.

She has a shower and we watch. She has unsatisfying sex with her husband and we watch. She has a brief conversation with her son. She goes and talks about her sex life with her psychiatrist and makes a pass at him, which he declines while acknowledging finds her attractive. She goes to a museum, picks up a stranger and has sex with him. Preparing to go home, she’s horrified to see a letter saying her sexy stranger has been diagnosed with syphilis and gonorrhea – and as she takes the escalator out of the building, she’s grabbed in the elevator and killed.

Why did we need to see that this guy may have given her STIs?

By the Psycho patterning, it’s a plot that we expect to go somewhere, like Marion’s theft, and then we’re shocked that someone else steps in to murder her. On paper it makes sense.

But in practice it doesn’t work like that.

Marion’s theft is deeply relevant to the events that follow: she’s the third young woman Norman Bates has murdered, and it’s only because a detective is chasing the money she stole that he gets caught. The other two simply disappeared; they’re unsolved crimes until Marion unintentionally brings detectives into it. If she hadn’t been on the run, the odds are her death actually would have ended the story.

The STIs, though? It could have gone somewhere. Maybe the hospital is trying to follow up with Kate’s lover, and the follow-up leads to a witness. Maybe a previous hook-up he infected is on his tail, and she suspects him of the murder and takes over as new lead. But no: it’s just an extra little twist, a sprinkling of stigma to confirm that despite all her showering, Kate is a dirty woman.

Let’s talk about Hitchcock’s shower scene.

You don’t need me to tell you how good it is, but here’s a question: why is she killed in the shower?

It seems worth asking, especially since ‘Trans people attack women in bathrooms’ is such a political move these days. (https://williamsinstitute.law.ucla.edu/publications/safety-in-restrooms-and-facilites/ Honestly, do you know anyone it’s happened to? The only cis woman I know who was sexually assaulted in a bathroom was assaulted by another cis woman. I’ve certainly shared bathrooms with trans women and it was so unremarkable an experience I don’t even remember much about it, except that spaces that make a point of having gender-inclusive bathrooms also tend to be the spaces most willing to help with my mobility aid. Go figure.)

So why is Marion attacked in a shower? It’s quite an interesting question. The obvious answer is voyeurism: there she is, all pretty without her clothes. But in fact we don’t see very much; we actually see more of her in other scenes where she changes outfits and is fully onscreen in nothing but her undies. So while the shower might titillate the imagination, it’s not the whole picture.

Another obvious factor is that she’s at her most vulnerable: she’s naked, she’s backed into a corner, she’s in a place she assumed she could be completely private. And, too, there’s the practical factors for the murderer: the noise of the shower and the cover of the curtain make her easy to sneak up on, and a tub and tiled floor are easier to clean than a blood-soaked carpet.

But I think the strongest reason is thematic, and it’s one de Palma goes absolutely opposite to.

Marion stole money because she wanted a respectable life with her lover. All the way along the highway we can hear her inner monologue fretting about the many, many reasons she won’t get away with it. When she talks to Norman, she concludes by telling him that tomorrow she’s going to go home and try to undo the mess she made.

Marion sinned. Then she repented. The shower is a gesture of cleansing.

It’s a rather brilliant combination of the symbolic and the practical. Having resolved to wash away her sins, Marion washes herself – something people really do if they want to draw a line between themselves and a bad experience. It’s been a long and terrible two days of travel and fear, and now it’s time to scrub that off and, physically as well as morally, start afresh.

Cinematically, Marion dies innocent.

De Palma’s Kate, on the other hand? Her part of the movie lasts half an hour. She has one conversation with her son – the character that’ll carry the plot forward the way a detective does for Marion, but who unlike the detective is completely unconnected with anything she does in the entire rest of the movie.

Which means that narratively, Kate could have been doing absolutely anything else and the plot would have worked the same. The person who witnesses her death is a total stranger who just happens to be there by pure coincidence, and she’s the one who brings Kate’s son into it. Kate could have been spying for the Soviets or taking classes at clown school and it would have had the exact same relevance to the plot.

But in every scene except for the one with her son, Kate is either fucking, talking about fucking, planning on fucking, worrying about the consequences of fucking, or showering naked and making the audience think about fucking. Even the presence of her son is hard to disconnect from her sexual presence entirely; not when the movie makes such a big deal out of her sexual relationship with his father.

So what’s the shower scene for? The same as in A Woman Kills: the presumed audience just wants to look at women naked, and isn’t expected to justify that any more than they justify their assumption that a man who wears dresses must be a dangerous pervert.

You’ll notice I’m talking more about the sexism than the transphobia.

No doubt this is largely because I’m a cis woman and this is the part that’s familiar to me. But it’s also because the portrayals of a queer killer are so outlandishly unreal that it’s quite difficult to say anything about them except, ‘They’re a lot of nonsense.’

De Palma’s is the worst in terms of psychological garble. The murderer is a psychiatrist who, like Norman Bates, kills women he’s attracted to, but there’s none of Psycho’s care in at least trying to distance itself from blaming the sexuality. On the contrary, the script explicitly and rather unpleasantly links the two:

A transexual. About to make the final step, but his male side couldn’t let him do it . . . There was Dr Elliott and there was Bobbi [the woman] . . . Opposite sexes inhabiting the same body. The sex-change operation was to resolve the conflict. But as much as Bobbi tried to get it, Elliott blocked it. So Bobbi got even . . . Elliott’s penis became erect, and Bobbi took control, trying to kill anyone that made Elliott masculinely sexual.

I don’t think we needed to hear that much about anyone’s parts, do you?

Here’s an example of the confusion between sexuality and gender, we can note: plenty of trans women are attracted to women, not because they’re masculine but for the same reasons cis women are – ie, some people are into girls. But the film rather glibly conflates having an erect penis and wanting a woman as equally ‘masculinely sexual’.

It’s lazy all the way down. The script can’t tell the difference between being trans and having – not even actual Dissociative Identity Disorder, but movie-crazy multiple personalities. It doesn’t even make sense diegetically. Transitioning is later described as as ‘all they [trans people] want to do.’ All.

So if all Dr Elliott wanted to do was transition, why would he also not want to transition? This is Norman Bates with the not-being-trans removed, and as well as demonising trans people in a way that’s probably still influencing stereotypes, it simply doesn’t make any sense.

Also Liz, the witness and amateur detective, is a sex worker, and there’s no narrative reason she had to be that either. I’m all for positive portrayals of sex workers, but I simply don’t trust de Palma’s motives here; it watches like he trusts sex workers more than other women because he reckons they agree that their lives should revolve around sex. And plot-wise, she does nothing that couldn’t have been done by any woman who could choose her own hours and was comfortable flirting. Nothing in this movie had to happen the way it did, except as excuses to portray heteronormative women as all about sex with men, and trans women as monsters.

Okay look. Carrie and Scarface are excellent movies. On form, de Palma was good at suspense.

But when it comes to Dressed To Kill – and Raising Cain and Body Double, come to that, because boy did he have problems with both dissociative identity disorder and a thing about sex workers?

Can we maybe agree that in this day and age of recorded media and streaming, and also freely available porn, we don’t really need these films?

The best scenes in Dressed To Kill are the ones where de Palma pastiches Hitchcock, in particular Vertigo. In 1980 most people didn’t have VHS players and wouldn’t be able to watch either movie unless it was rerun at some local cinema, but those days are gone. Now if we feel nostalgic for Hitchcock, we can just watch Hitchcock.

In an era of Blu-Ray and streaming, Dressed To Kill feels extremely bargain-basement. If you want porn you can get porn; if you want Hitchcock you can get Hitchcock. And if you want a trans-monster film with some interesting technical experimentation you can watch A Woman Kills. Dressed To Kill doesn’t feel necessary.

Unless you want to make women uncomfortable. Its story isn’t just a world of sexual contamination and danger; it’s a world where for women, there’s no other kind of sex. Men get the pleasure of watching soapy tits, but for heterosexual women in the audience the options are: bad housewife sex, regrettable sex with a disease-spreader, paid sex with a customer, or making a pass at your psychiatrist who later stabs you.

The only positive relationship between a man and a woman is between the deceased Kate’s son and murder witness Liz, and while it’s sweet, it’s definitely platonic. She’s a high-priced call girl in her twenties; he’s a teenage computer geek in the era where you still called such people ‘inventors’, and the best outcome for them is definitely friendship.

There is no safe sex for women in this world. Neither is there respectable sex: your best chance is to be a sex worker and honest about it. You’re there for the audience to look at in private moments when you just want a shower, or to get stabbed and menaced.

So it’s not very surprising that if it influenced how cis women think of trans women, it’d foster fear and disgust. It is, for women, a pretty nasty film. It’s just a mistake to attribute any of that nastiness to trans people, because apart from the prurient details of vaginoplasty, it has no interest in real trans people at all.

It’s the same old dodge: when a man kills women, blame it on something other than men. But there’s a progression.

Psycho did it in 1960 by blaming a mother; it tried to disavow transphobia but it certainly didn’t proof itself against it.

In 1968, A Woman Kills blames a mother and a man being feminine.

In 1980, Dressed To Kill didn’t bother to put in a tragic backstory: the murderer is gender-nonconforming and that’s all that needs to be said.

We can’t talk about this trope without talking about The Silence of the Lambs in 1991. I won’t waste your time telling you what a well-made film it is because you already know that, but what’s relevant here is that it addresses the fact that’s extremely present in movies like A Woman Kills and Dressed To Kill: men stare at women. Our heroine, Clarice Starling (Jodie Foster) is trying to do her (traditionally male) job and hunt down a killer, but wherever she goes, she runs into the male gaze like it’s a brick wall.

‘Don’t you feel eyes moving over your body, Clarice?’ gentleman-murderer Hannibal Lecter asks her, and of course she does. As Ellis puts it in her video, it ‘deliberately sort of flips the male gaze.’ There are gazing males everywhere; it’s just that they aren’t unseen. The camera stares back at them.

All of which is good, and why a lot of people still consider it a feminist classic. It’s just that it can’t get past the idea that killing women is somehow unmanly – and therefore it’s something other than men responsible.

Hannibal Lecter has, diegetically, attacked at least one woman. But the way it’s framed is quite careful: we don’t see it on screen, and the distress it causes Clarice is neatly deflected away from Lecter.

No, when we learn about Lecter’s attack on a woman the more immediate bad guy of this scene is Dr Chilton, head of the institution where Lecter is imprisoned. Clarice comes to interview Lecter and has to meet Chilton first; Chilton makes a rather slimy pass at her which she deflects as politely as she can. Offended, Chilton makes a point of showing her a photograph of one of Lecter’s previous victims – and more, he makes it clear that the victim, a nurse Lecter attacked in hospital, is what Clarice will become if she doesn’t follow Chilton’s rules.

We don’t see the picture. We see Clarice’s horror – and we see Chilton’s chilly sleaze as he produces the photo and says, ‘He did this to her.’ A small assault is taking place in this scene, Chilton taking revenge on Clarice for rejecting him. It’s sexual harassment in the workplace – and it acts as a distraction from the greater assault on a woman we’re told Lecter committed.

On screen, meanwhile, Lecter (Anthony Hopkins) is positively courtly to Clarice – and when we see him attack people, they’re always men.

So what we’re shown on screen, more often by far than direct violence, is micro-aggressions against Clarice. Everywhere she goes, men make it sexual when she doesn’t want them to, and it forms the emotional background of the murders: a world where women are surrounded by predatory eyes.

We know Lecter has assaulted a female victim, but all the mistreatment of women we see is tied to the male gaze – and so is the queer killer, Buffalo Bill.

Lecter, explainer of criminal psychology, makes this link explicit in dialogue. That observation he makes about ‘eyes moving over your body’ is in the middle of a speech explaining what the uncaught Buffalo Bill’s real motivation is: he ‘covets’, and ‘We begin by coveting what we see every day.’ The male gaze Clarice experiences is directly linked to the murderous gaze of Buffalo Bill – which makes it impossible, thematically, not to see Bill as just the extreme logical conclusion of the common or garden male letch.

The Silence of the Lambs tries, like Psycho tries, to disclaim any slights on actual queer people: Buffalo Bill is ‘not a real transsexual,’ Lecter explains. It fits perfectly with the linking of his gaze with the regular male gaze: he is, perhaps extremely, male. But since the film doesn’t include any ‘real’ trans people to counter the image of Bill cavorting around in a literal fright wig, this is the images of queerness the film leaves us with.

The story is moving forward – although it can always be moved back again, as witness J.K. Rowling’s Troubled Blood. (Which I haven’t read and am not prepared to put money towards, so I won’t comment on it, but we all know that man-in-a-dress-kills-women is its thing. The essay by Lindsay Ellis I linked above discusses it in more detail, so if you want to hear from someone who has read the book, that’s a good place to start.) The audience gawping at women as the necessary corollary to the queer killing doesn’t seem to have lasted, and how many disclaimers the script uses to soften the visual portrayal of man-wig-dress-knife varies.

But it is what it is: a fictional trope with very little basis in reality. History contains the odd serial killer who cross-dressed, but if you believed the movies you’d think murder was a regular feature of queer life.

What are we going to do with this?

There’s a curious little palette-cleanser than turned up recently.

Let’s talk about another obscure film on Shudder from 2024, rejoicing in the extremely cabaret name of Satranic Panic. It’s a million miles from de Palma’s gloss; its budget was clearly about ten Australian dollars and a lot of favours from friends, and there are points where it is, I’ll be honest, endearingly amateurish – or at least, obviously a piece of juvenilia. Writer-director Alice Maio Mackay was apparently twenty years old when she made it (https://thetwingeeks.com/2024/09/01/satranic-panic-a-fiercely-new-queer-transgender-original/), and it is definitely the work of a young filmmaker.

An incredibly impressive young filmmaker. Who gets that much done at twenty?!

It has rough edges. And I do not have the heart to hold any of them against it. I love this movie, because it conveys something the world desperately needs more of: trans joy.

What’s trans joy?

Well, ask different trans people and you’ll get different answers, but the basic point is this: getting to live as your authentic self, especially when supported by a loving community, can feel wonderful. We talk a lot about the pain of both repression and oppression, which we should, but we can also talk about the fact that being able to live as the gender that’s right for you feels good.

Again, I’m a cis person and I can only talk about this from the outside. The best I can say is that on occasion I’ve spoken to a trans person and they’ve said something about their decision to transition and how they’re happy with it. Always, I’ve seen a light come into their eyes, a clear, uplifted rejoicing that shines like a sunrise. It’s a sight of something deeply natural and right. There’s lots of reasons to be against transphobia, but even if you leave out violence and oppression, it comes down to this: opposing trans rights is demanding the right to take the light from someone’s eyes.

Satranic Panic isn’t mainstream, it’s a budget indie flick on a mid-sized streaming platform – but even if it’s a bit messy, it has that shine. It’s just fun. So I want to call attention to it.

And it has an odd little take on the queer killer.

Meet our scrappy heroes.

Aria and Jay have suffered a terrible loss. Aria (Cassie Hamilton, one of the co-writers) is our lead: she’s a trans young woman who makes her living singing in drag shows. Jay (Zarif) is her buddy, an aspiring comics artist and non-binary. They share a touching found-family relationship; they confide, they joke, they tease, they fight, they turn to each other with absolute assurance that if no one else will be have their back, at least one person will.

But there used to be three people in this family. Max, Jay’s boyfriend and Aria’s brother-from-another-mother, has been murdered. He was trans as well, and there’s a Satanic cult hunting down trans people.

By ‘Satanic cult’, I mean literal demons. We begin seeing Aria sing onstage, one of several numbers she performs; like A Woman Kills, this is a musical by the back door, and Hamilton is really very good. But afterwards in the dressing room, a middle-aged guy comes in and sleazes up to her.

You’d think he was just a chaser, but no. Aria’s last injection from her endocrinologist left her with a magic power: she can sense the presence of demons.

You’d think, given the obvious budget constrictions, that Satranic Panic would be conservative with its special effects. Nope! The guy whips out a long, burning tongue and grabs Jay’s arm with it. You hear the sizzle, you see the smoke rise. Aria stakes him from behind. He catches fire. We can see that the CGI budget was beyond ‘low’ and into the realms of ‘bless you’, but Mackay blocks the action with a clarity well above many Hollywood directors: it’s legible, pacy, and holds your attention well enough that the cheapness doesn’t matter. When it comes to action, the movie aims high and hits the target.

When it comes to the plot, it can be a bit rough. The basic story is a good old revenge quest: Aria and Jay hit the road to hunt down the rest of the demon cult that killed their beloved Max. They have encounters and kill monsters. Aria beats one of them to death with a disco ball.

On the way they pick up Nell (Lisa Fanto), a possible ally who Aria is immediately smitten with and who Jay doesn’t trust, so there’s a bit of a falling-out before the final conflict. All decent drama staples. The Aria-Nell romance is a bit rushed in all its stages, and the dialogue scenes can go on too long, and in general the pacing can be a little uneven, but these are the faults of a still-developing team of artists and the verve carries you through.

In the climax it turns out that the cult-leader villain is not only Nell’s father, but was also Max’s: he’s on a quest to destroy transness by any means. ‘Sure, I could have found some angry young men to join my cause,’ he says, ‘but the right just isn’t what it used to be.’ Demons, being ‘pure’ and also completely obedient, served his turn better.

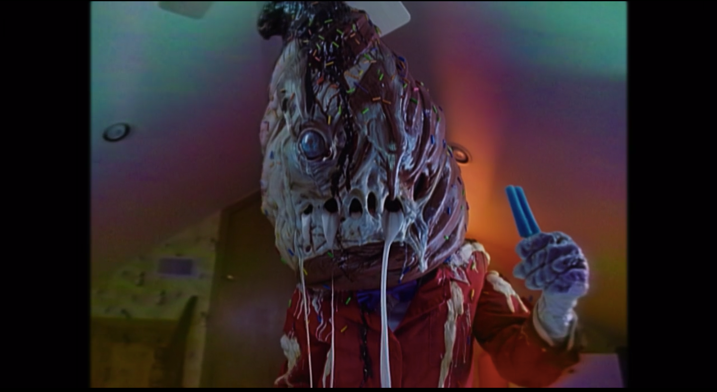

Of course they defeat him and justice is done. But do you notice what he’s wearing?

Here’s where the queer killer takes an unexpected turn.

Dr Fenway is an endocrinologist tracking former patients, yes, and a demon-raiser. But he’s also . . . well, he insists he’s ‘in drag.’

Aria, accurately based on all the villain speeches, instead insists that Fenway is a trans woman in denial. ‘There is a difference between drag and trans,’ she says, ‘and sweetie, I think you know that. You want to wipe out all trans people – wipe out me – because you’re jealous of me. Of how happy I am. Of how hot I am.’

This part of the story is massively emphasised. Over-long, really: the writers are still maturing and the dialogue in which characters argue over their ideology is on-the-nose and in need of an editor; it’s the least polished part of the movie. There’s another part of the conflict where Dr Fenway allows Aria to say some ‘final words’ before setting the demons on her, and she sings them, and then he starts singing too and it turns into a song-off, and that’s the kind of splashy exuberant fun where Satranic Panic shines.

But here, dwelled on with passion, is a new and different take on the killer-in-drag. Yes, Fenway is murdering people because he/she is female. But it’s not because of heterosexual attraction, or sadistic fetishism. It’s because he/she can’t bear to see trans people enjoy the freedom Fenway denies him/herself. The victims aren’t cishet sexpot sinners; they’re trans people who didn’t do anything wrong.

Now, this is another trope that I know a lot of queer people don’t like: the ’phobe whose hatred is really queerness in denial.

There are good reasons to object to it, primarily that it locates the blame for persecution within the persecuted community. Statistically speaking some ’phobes will be queer because a lot of people are. People are messy. But letting the cishets off the hook for bigotry is like letting straight, masculine men off the hook for serially murdering women: it won’t do. Mostly when people kill us, it’s not because they’re struggling with some aspect of themselves; they just like killing us.

But in this case?

Well, in isolation I’m not sure what I think about it. I’m not trans and it’s not up to me to decide what is and isn’t an objectionable use of the self-hating queer trope.

But boy is it refreshing to see it finally acknowledged that what draws this killer is something right about the victims, not something wrong. Because with this kind of film, that’s pretty much unique.

Marion was a thief; a penitent one, but that’s what got her into danger. A Woman Kills makes sure we know the victims are sex workers, it makes sure we get a good look at them naked, and it’s not exactly brimming with worker solidarity for them.

Dressed To Kill is explicit that the victims got themselves killed by flirting, and flirting inappropriately with a psychiatrist at that; if they’d behaved themselves, Dr Elliott would never have gone after them. Even The Silence of the Lambs makes a point about Buffalo Bill’s victims; contrasted against the impeccably dainty Foster, all the girls Bill kills are overweight – a definite stigma in today’s sexual culture, and their size is emphasised as the reason he chose them.

One way or another, these victims are all fallen women. There’s something about them that makes them lower status.

But the victims Dr Fenway kills? They were just unbearably cool. Fuck the murderer; the victims were better people.

In the real world, trans people are far more often the victims of violence than the perpetrators. If we have to have this trope of the queer killer, it’s great to see a film that actually acknowledges this, and acknowledges that the problem here lies with the killer, not the victim.

And whatever else is going on, it really is lovely to see a film that actually revels in the joys of transness.

The lighting is vibrant and colourful. The clothes are hip and bright. There’s a swagger and a gallows humour Aria and Jay bring to their quest that shrugs off traumas and keeps on trucking, because what else do you do when it’s laugh or lie down and die? They’ve left behind any shame about defending themselves; it’s time to kill demons. As Aria says, ‘All trauma gave me was biting wit, an incredible voice and killer tits.’

In particular it’s a celebration of trans art and culture. Notably, Aria raises the roof with her musical numbers. I’ve had the fun recently of watching a dear friend develop a musical about living different in a bigoted world, co-written and performed by a team of queer and gender-nonconforming artists, and I see a lot of the same energy in Satranic Panic. When you see joyful work by and for this community it has this wonderful exuberance: too much feeling, too much playfulness, too much openness to transformation to be contained within a single genre. So you sing, you joke, you get fantastical. You won’t be contained.

Too, there’s a real love of the faces and bodies of its characters – not leering, but actual gazing. Aria’s face dominates the screen over and over again: Aria resplendent in full stage make-up; Aria covered in enemies’ blood; Aria tired and stressed and having an ordinary difficult day. The camera treats her as a figure worthy of close and sympathetic attention.

Jay’s performance is gentler, but the camera loves them too; their beauty, their pensiveness, their sincerity and emotion are recorded with care and reverence.

Along with the bright colours, there’s a cinematic tenderness and respect for the real people in the midst of this hyper-real story, and it’s this more than any of the speeches that brings forth its best argument for the rights and dignity of the heroes. It’s not an argument that needs to be made to queer viewers, of course, who are obviously the target audience – but if you need any convincing, its best message is in its characters’ very existence. Who could hate these people? Why would you hurt these people? Look at them. Look how fun they are. Look how beautiful they are. Look how imperfect and loving and human they are.

(Incidentally, if you also want to check out my friend’s show, it’s a banger – toe-tapping songs, adorable characters, heartfelt emotion and raucous laughter. Its working title is Others; it’s a sci-fi dystopian comedy about people in a world that persecutes them for their slightly naff superpowers. It’s being developed in London, so watch out for performances. It’s a joy. Here’s the Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/others_musical/; here’s the Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/p/Others-Musical-61555951912731/)

Which is why Satranic Panic is a better defence than any psychologist’s disclaimer.

You can bring in Psycho’s shrink or Dr Lecter to explain that a queer killer in a dress isn’t actually a representative of that community. It doesn’t stick; you just get imitators who miss the point. But if you put actual members of that community on screen and let the audience love them? Satranic Panic’s confrontation with the murderous doctor isn’t what’s going to stay with me; I’m going to cherish memories of seeing Aria and Jay hit the road to kick arse.

While we’re here, let’s talk about the flip side.

Satranic Panic is a rough-edged and exuberant piece of juvenilia from a director I hope to see more of. But if you want a well-finished movie from a gender-nonconforming point of view, of course we need to talk about last year’s I Saw The TV Glow, directed by Jane Schoenbrun.

Remember how I talked about ’phobia wanting to take the light from people’s eyes? I Saw The TV Glow is a film about what it does to you when that happens.

Owen (Justice Smith as an adult, Ian Foreman as a child) is a lonely suburban kid. Something’s off and he doesn’t know why.

Well, I say ‘he’. That’s the pronoun Owen uses about himself. If he was able to face what was inside him – if he could see it in his life rather than just behind a TV screen – that pronoun might be ‘she’, or possibly ‘they’. But I have to call him something, so I’ll call him what he calls himself. Even if it feels like hurting him just to say it.

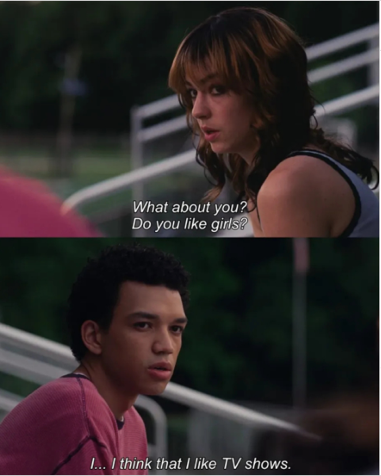

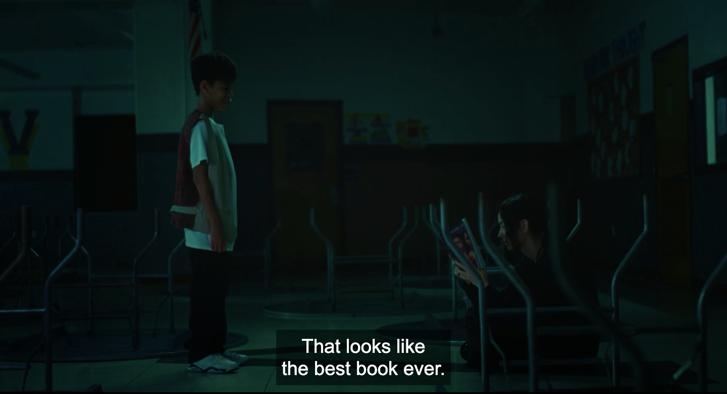

Owen is lonely. He’s quiet, good, keeping his head down. But there’s a TV show he wants to watch, The Pink Opaque; his strict parents won’t let him stay up late enough to catch it. He isn’t sure why he wants to watch it so much; there’s just something about it he can’t articulate that makes it mean . . . something.

Maddy (Jack Haven) is a defiantly weird kid. She – they? He? Maddy is more clear about being different but never explicitly names a pronoun, so I’ll go with ‘they’. They’re the world’s biggest Pink Opaque fan; they’re openly obsessed with it, saying plainly that it feels more real than their real life, that its characters feel like their real family. Maddy is all about this TV show, and not about to apologise for it. Maddy sees something they want to reach.

Owen sees Maddy reading an episode guide and plucks up the courage to talk to Maddy. They’re a couple of years older than him and not exactly friendly in the conventional sense, but if they can talk about The Pink Opaque then they’re prepared to talk. Eventually the two build up a tentative friendship based around one sleep-over where Owen gets to see the show live, followed by a long period where Maddy tapes the show for him and leaves the videos for him to watch in the school’s AV room.

What is this show? Well, ostensibly it’s one of those 90s supernatural shows for teens. Most explicitly it’s modelled on Buffy the Vampire Slayer; its titles use the same font, and they stunt-cast Amber Benson, formerly a star of Buffy, in a small part as the mother of one of Owen’s friends.

The story is only sketched in: it’s about two girls with magic powers who can connect on the astral plane, who fight monsters-of-the-week, and whose ‘Big Bad’ is a figure modelled after Georges Méliès’ 1902 silent classic A Trip To The Moon called Mr Melancholy.

But the literal content of The Pink Opaque isn’t the story. The story is about two kids who don’t fit in, who find something in this TV show that speaks imaginatively of something that nobody in their real lives is talking about. What’s literally happening on the screen isn’t the point; the point is that it captures a feeling that speaks straight to their souls. It evokes a world of outsiderdom, of having something powerful inside you that ordinary people wouldn’t understand, something that matters more than anything ‘normal’.

Then The Pink Opaque does that thing that devastates people who can’t see themselves in their own lives, who have to draw more comfort from fiction than polite society considers grown-up or dignified. It stops on a cliffhanger – and then it gets cancelled. It finishes with one of our heroines apparently defeated by Mr Melancholy, her heart removed and her body buried alive.

And in different ways, neither Maddy nor Owen can survive this. Not when it was all they had.

Maddy knows they’re attracted to girls. Owen knows there’s . . . something. He doesn’t know what. Small moments here and there show times when he was safe with Maddy, or perhaps just dreaming with Maddy, where he wears a dress.

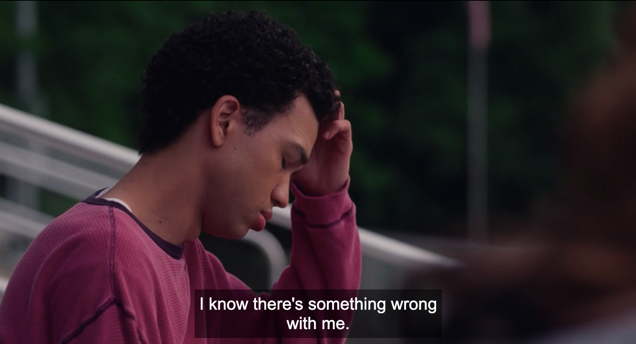

‘It feels like someone took a shovel and dug out all my insides,’ he tells Maddy. ‘I know there’s nothing in there, but I’m still too nervous to open myself up and check. I know there’s something wrong with me. My parents know it too, even if they don’t say anything.’

Maddy has some kind of answer. They just don’t know how to express it except through talking about The Pink Opaque. ‘Maybe you’re like Isabel,’ they say, referring to one of the characters. ‘Afraid of what’s inside you.’

And they’re right. But Owen, who was brave enough to talk to Maddy, never finds the courage to look.

Owen tries to live a normal life. Maddy, though, disappears. Then they come back claiming they found the other plane by burying themselves alive, just like the ending of The Pink Opaque. They ask Owen to join them. But he doesn’t. He can’t. It sounds like suicide. It sounds too crazy.

It sounds too magical to believe.

Maddy’s stepfather was abusive. There’s nothing keeping them to this world. But Owen’s family, while not perfect, weren’t abusive – just limiting, restrictive, a space he tried to fit within. And whatever’s inside Owen, he simply can’t accept that it’s more dangerous to stay where he is than do whatever wild-sounding escape attempt Maddy – now using a different name and looking more masc – is proposing.

Maddy disappears from his life. He decides, ‘It was time to be a man.’ He gets a job, a family, a home.

‘What if I was really someone else?’ he wonders all his life. ‘Someone beautiful and powerful? Someone buried alive and suffocating to death?’

And when he tries to watch The Pink Opaque again as an adult, it’s not how he remembered: it’s shrunk to a goofy kids’ show and he’s embarrassed he once cared so much. He’s lost the magic of childhood. He no longer believes he could have that magic as an adult. He’s tried very hard to push down the part of him that once responded to this fantasy.

And he’s slowly dying. It just doesn’t show on the outside.

Maddy’s suggestion might have destroyed them. Staying is destroying Owen. He just doesn’t know how to stop.

As the film ends, Owen is stumbling forward at his workplace, terrified, exhausted, apologising to everyone he sees for having a panic attack.

This is another answer to the killer-in-a-dress. Owen doesn’t want to kill people; he’s a gentle person and the last thing he wants to do is hurt anyone. That’s part of why he can’t be open about who he is: he lives in a place where coming out would meet pushback and he’d have to accept the role of troublemaker, and he wants to please the people he loves.

He is trying to keep whatever’s feminine about him concealed; he’s trying not to be different, the way you’re supposed to if you want to be ‘normal’. But it’s not about attraction; it’s not about his penis. It’s not about sex. It’s certainly not about hurting anyone else. It’s about selfhood.

Owen is undergoing that same struggle that keeps coming up in these movies. He is in conflict with herself.

And this conflict between normative and trans is killing someone all right. It’s killing Owen.

Can we talk about trans people without talking about violence? Of course. But maybe not in a horror film. Not today.

But maybe we can direct it where it belongs.

There are violent feelings at play. Historically, those have been felt by cis creators and attributed to queer characters. When queer people take the helm, though, we see something different. It can be piercingly melancholy as in I Saw The TV Glow, or it can be raucously splashy as in Satranic Panic, but they say the same thing: if I can’t be who I am, that is violence. You just may not see how deep it cuts.

I Saw The TV Glow is the more polished of the two films, undoubtedly: it’s poised and elegant and it’ll tear your heart out. You should absolutely watch it. But if you have access to Shudder, maybe also check out Satranic Panic afterwards so that you can see the hope and the laughter as well as the pain.

The killer-in-a-dress is like a slasher villain: however often we put him down, he keeps coming back.

Sometimes he comes back in good movies, and in those movies he comes with disclaimers: this isn’t a real queer person, real queer people aren’t like that.

But if you don’t also see real queer people, what are you supposed to think they’re like?

The answer, if you ask Jane Schoenbrun, is magical, vulnerable, beautiful enough to make you cry. If you ask Alice Maio Mackay, the answer is ferocious, unbreakable, beautiful enough to make you cheer.

I don’t have an answer to the trans-killer stereotype, but I want to hear what queer people have to say. When they answer back to this story, that’s when we start to hear magic.

It’s bad out there for trans people right now. We need whatever we can get to remind us how beautiful it can be.

Further Reading

Kit Whitfield’s “What’s On Shudder” articles are a must-read for any horror enthusiast looking to enhance their streaming experience. These articles offer a comprehensive guide to the latest and most exciting horror films available on Shudder TV, diving deep into the genre’s rich tapestry. One of the standout features of Whitfield’s work is her unwavering passion for horror, which resonates throughout her writing. She not only highlights key films but also provides insightful commentary on themes, directors, and the evolution of horror as a genre.

Additionally, her articles often include hidden gems and lesser-known films that might be overlooked in the crowded streaming landscape. This can lead to discovering unique stories and innovative filmmaking that challenge conventional horror tropes. Whitfield’s expertise ensures that readers gain a better understanding of the films’ cultural significance and artistic merits.

For both die-hard horror fans and newcomers alike, checking out “What’s On Shudder” is an invaluable resource for finding thought-provoking content that goes beyond mere scares. Her engaging style and knowledgeable perspectives make the horror genre accessible to everyone. Whether you’re in search of a terrifying thrill or a deeper exploration of cinematic horror, Whitfield’s articles are the perfect companion for your Shudder journey.