Weaveworld Stories Without End: My Life In Horror

It had to happen eventually. I’ve been reluctant to approach it, because I have no idea how to do the subject justice. How, exactly, does one discuss a work that altered the topography of one’s own mind? That blew wide the doors of perception, tore through every structure and assumption with the force of a delirious apocalypse?

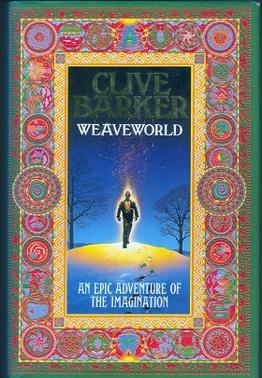

For me, Clive Barker’s Weaveworld is a sacred text: It changed me. It changed everything.

Weaveworld: A Sacred Text

Up to the point of my original exposure, my knowledge of Barker’s work threaded no further than the Hellraiser franchise. I didn’t even know that the man dabbled in written fiction (or that his mastery of the form was so unequalled). Weaveworld came to me by complete chance (a coincidence that my penchant for pattern-seeking and seeing providence in the world has mythologised in memory):

A tertiary text that came as a free extra from my Mother’s book club, the beautiful hard-back volume boasts the eponymous “Weave” on the dust-jacket, a mesmerisingly colourful piece that tells the entire story in symbolic form.

At that time, my experience of Fantasy fiction was expansive in terms of the number of books and authors I regularly consumed, but somewhat narrow in subject: Tolkien, C.S. Lewis, Alan Garner and other familiar figures made up my repertoire. As such, my understanding of Fantasy as a genre was somewhat codified (consisting of that peculiarly British tradition Tolkien popularised).

At the age of 11, whilst I’d begun to understand my own queer identity in a nascent, inarticulate fashion, I still hadn’t expressed or apprehended what it meant or consisted of in any clear way (in retrospect, maybe that isn’t so surprising, since very little was on hand in the early-to-mid 1990s to provide the appropriate language or context).

An Apocalypse in Every Sense of the Word

Weaveworld plummeted into those assumptions like a falling star into still ocean; an apocalypse in every sense of the word. What emerged from the smouldering wreckage of that initial reading wasn’t the same creature who blithely sat down with the book. In many respects, the experience was as capital “R” Romantic as the imagery and metaphysics of the story itself: A Blake-ian voyage from innocence to experience, reality re-written and identity undone in a welter of revelatory metaphysics.

For the first time, I encountered a story that echoed my own inchoate fantasies and preoccupations, that expressed ideas and philosophies I barely understood in articulate terms, but which I felt with a fundamentalist zeal.

Here was a story in which the “real;” the lived experience of concrete and work and family and relationships weren’t presented in contrast or opposition to the realm of dreams, the tracts of Wonderland, but as part-and-parcel of the same engine, the same delirious carnival of human experience. I’d never in my young life encountered a story, a work in any medium, that so profoundly excited, left me breathless, shivering and feverish after reading.

The visceral sensuality, the raw and abiding realism of the book does not contrast the fey and fairy tale elements but informs them (and vice versa). Here, waking reality, the lived experience of humanity, isn’t separate from magic and the dreamed life of the species: They are integral components of the same phenomenon. The only reason any such distinction exists is due to extremely dark, materialistic and Fascist forces within humanity itself, that separate us from our internal, imaginary worlds, turning us against our essential selves and making us ashamed of what arouses and inspires.

Barker was the first writer I ever experienced who so beautifully defined that phenomenon, who emphasised the wonderful ambiguities and contradictions innate to being. Weaveworld is a wild ride through the unspoken soul of our species, a celebration of those essential elements that so much of our structures, cultures and traditions would render alien and unknown to us.

Here, sex and magic and miracles are all one: The peoples trapped within the eponymous Weave (a world woven into a carpet) are as capricious, complex and unpredictable, as various in their states and passions, as any human being (or “Cuckoo,” as they refer to us). Whilst they wield capacities we might call miraculous, to them, they are “. . .no more remarkable than the fact that bread rises.”

By the same token, those that are aroused from their long stasis in the carpet earlier than the rest find themselves enchanted by the 20th century in all of its material excess: Having missed events such as the Industrial Revolution etc, to them, what we consider everyday conveniences are marvels, as -if not more- miraculous than the arts -or “Raptures”- they wield. The collision of the two worlds, the fresh eruption of magic into materialist, 1980s Liverpool Suburbia, draws the essential tension the book wrestles with:

Are we ready, as a species that’s been actively dulled to and alienated from its capacities for the miraculous, to accept and understand our own dream-lives when they’re made readily available to us? If we woke tomorrow and found doors to Wonderland open all around, would we be able to walk there without poisoning or destroying it with our materialism, our terror of the other, our neurotic need to own and control?

The Banality of Evil: Shadwell The Salesman

Barker’s less-than-flattering commentary in that comes in the form of the novel’s central villain, the grotesque shyster, con-artist, fraud and “salesman,” Shadwell.

Having become acquainted with magic and miracles -via association with a rogue element from the Weave by the name of Immacolata-, Shadwell sees nothing but the opportunity to own, to control, to make himself the master of. His imagination and desires thread no further; he is, as Immacolata herself points out, hideously limited, a creature of dull-witted and finite passions, almost null imagination. His abiding thought, having found that Wonderland exists, is: “How can I own it, and what can I sell it for?”

Shadwell is amongst the most grotesque evils Barker ever draws in his fiction. And, given that he shares space with a demi-Goddess bent on genocide, a rapine ghost that makes monsters from its own abortive children and an entity that is a literal angel of apocalypse, that’s no small feat.

Shadwell eclipses them all in terms of pure, human excrecence, despite -ostensibly- having no supernatural capacities or powers at all (save those that are gifted to him). The story -and, by extension, its author- casts Shadwell as the very avatar of all that’s poisoned, broken, toxic in humanity: The stunted, petulant desire to objectify, own and control. Presented with miracles, Shadwell -contrasted to protagonists Calhoun and Susanna- is utterly unmoved:

He isn’t changed or inspired by the experience. He doesn’t feel revelation or the blossoming of potential: All he sees is opportunity. He is, psychologically, the very portrait of the narcissist, the abuser: One whose profound lack of imagination renders him inured to its expression or promise. He is The Salesman, The Capitalist, The Televangelist and The Politician. Even when forced to shed one mask and don another -usually compelled by circumstance-, he doesn’t sincerely change: He, like all good salesmen, is chameleonic, donning and sloughing identities as a snake sheds skin.

But every mask he dons ultimately has the same purpose: To con, to defraud, to manipulate, to control. It’s a sublime irony that one of the most brilliantly magical concepts in the book -one that, ultimately, proves key to its resolution- is initially boasted by Shadwell, and becomes emblematic of his character:

A magical jacket that, when opened, provides the observer the image of their heart’s desire. It is, of course, a delusion; one the jacket and its wearer use to enslave their victims through sentiment (almost everyone gulled by Shadwell’s jacket conjures some material item to which they’ve attached profound sentimental value. In and of itself, the concept serves as a sad condemnation of the way post-modern materialism enslaves our most intimate passions, and opens us up to abuse and manipulation by the worst among us).

Shadwell later -reluctantly- abandons his status as Salesman, realising that imagination and miracles cannot be sold, and instead becomes an evangelical prophet; the kind of politicking, grubby con-merchant one might recognise from certain evangelical churches or insidious cults: Through that status, he inveigles the “Seerkind” -the inhabitants of The Weave- and turns them against themselves in fundamentalist fervour. All the while, he seeks to commit the ultimate taboo: To enter the Fugue, the very heart of the Weave, where the magical engine that holds it together resides. His ambition has gone beyond material ownership; now he seeks a more fundamental species of control: Possessing the magic of creation itself and thereby becoming a god.

However, as his erstwhile ally, Immacolata, points out: He’s still prey to the limitations of his own assumptions and impoverished imagination. He is still, at heart, a materialist. And so, when he arrives at his destination and finds no physical machine or engine to take possession of, he becomes infantile in his entitled fury, murderous and destructive, defeated at every turn by the one thing he can never own, sell or control:

Dreams. Imagination. Magic itself.

He thus commits an act of murderous desecration that undoes the magic of The Weave, murders Wonderland around him (Shadwell is of the ilk that: If he can’t have Wonderland as his own, then no one can).

It’s in this apocalyptic moment we see his final apotheosis: From would-be godhead to scorched-Earth fundamentalist. Since the Weave and all it represents resisted and defied him, it must, by definition, be evil and wicked. He thus embarks on a jihad against magic itself, allying with a self-fancied angel that is the living fire of God’s wrath made manifest.

Shadwell stands so far beyond -and below- most of Barker’s villains as a sincere representation of human evil, there’s very little competition: Unlike the vast majority, there’s no ambiguity here, no hint of wider poetry or complexity that renders him sympathetic. He is execrable; the very incarnation of 21st century materialism, narcissism and emotionally stunted entitlement. He is Donald Trump, he is Katie Hopkins, he is Jordan Peterson and Andrew Tate and Nigel Farage and every insincere, grifting demagogue that bedevils our cultures and history as a species.

A Grotesque Mirror of Our World

And, for all of his limitations, his often absurd lack of vision, he is still dangerous enough to obliterate Wonderland itself, to almost scour miracles from the face of the Earth. In that, he is a sublimely acute rendition of present-day Fascism, in all of its multifaceted grotesquery.

He’s contrasted by other villainous and antagonistic figures, all of whom represent some facet of humanity and its cultures Barker regards as corrosive and antithetical to sincere humanity:

The aforementioned Immacolata, initially Shadwell’s ally, and the one responsible for exposing him to the hidden world of magic, is a villain of an entirely other order: One of Barker’s great mythological antagonists, and thereby afforded more in the way of complexity and ambiguity than the entirely loathsome Shadwell:

Immacolata represents one of Weaveworld’s abiding themes: The taking of mythological archetypes and inverting expectation of them. In Immacolata’s case, she is a particular archetype of femininity and “womanhood” that recurs and recurs in our folklore and oral traditions: That part of the classic “triune goddess” that embodies “The Maiden,” virginal purity (her two undead sisters, likewise, incarnate the other two aspects of that archetype: “The Mother” and “The Crone” respectively).

But whereas, traditionally, that archetype is a matter of patriarchal prescription; a reduction of “womanhood” to a reflection of entirely male desire and requirement, Immacolata takes the essence of the concept and beautifully lampoons it:

Her “purity” is so absolute as to render her terrible and alien, horrifying to the men she despises, and who cannot abide the awesome power and authority her condition affords (there is a sequence in which even her shadow, cast from her levitating form, is enough to induce heart attacks and insanity in those it falls on). She is “pure” in a way that is alien and unobtainable; not as some prize for whatever male proves worthy. Her virginity is self-authored because no one and nothing in all creation is worthy of her. And that lends her power and lethality that is truly terrifying.

She is one of many demi-goddess characters Barker has conceived; a Feminist parody of the traditions and archetypes that litter our patriarchal histories. And, in that, she is uniquely fascinating; a creature that inverts assumption and expectation by virtue of her existence, and whose breath-taking absolutism is a fantastic contrast to the grubby narcissism of Shadwell.

It is notable that, for all her utter villainy -at the story’s opening, her entire motivation is to inflict “slow genocide” on the Seerkind for rejecting her as their natural Mistress-, Barker paints her -and her sisters; spectral revenants whom she purportedly strangled in the womb- with far more in the way of sympathy than Shadwell. Immacolata, for all her monstrosity, is an entity of magic and dreams, however horrifying, and therefore worthy of consideration. Whereas Shadwell is so utterly empty, wretched and ruined, nothing can redeem or endear him.

Immacolata occurs in the text as a bag of fascinating contradictions: Absolute and utter in sheer, lethal power, yet simultaneously afraid and vulnerable (at story’s opening, she suffers from visions of an evil purer and more cataclysmic than her own; the living fire known as The Scourge). She is contemptuous and dismissive of the men who follow in her trail yet also relies on them (her partnership with Shadwell is particularly fascinating). She is simultaneously an entity inured to love or sentiment, yet expresses affection for the spectral sisters she herself murdered. She is a uniquely female mythological entity, yet also the utter refutation of the traditions that spawn such.

Whilst Barker is well-known for his peculiar Feminism, Immacolata is another order of magnitude: Occurring as she does in an ostensibly Fantasy narrative, she serves to powerfully satirise contemporaries which incorporate similar mythological archetypes but refuse to deviate from their historical prescriptions. Here, “The Maiden” is re-imagined not as a patriarchal reduction of womanhood, but a reclamation of it so utter and absolute, it reduces those who encounter it to gibbering servility or outright insanity.

Later in the story, Barker complicates her further by polluting her purity; she is attacked by one she has wronged, severely wounded, her awful, distressing beauty destroyed. This renders her strangely vulnerable; a significant part of her power undone by the vandalism of her sepulchral perfection. Shadwell takes full advantage of this, the power dynamic between them shifting subtly but profoundly, to the point he ultimately comes to dominate her. Once again, Shadwell demonstrates what a toxic representation of narcissistic materialism and masculinity he is by assaulting Immacolata in the only way he knows how:

Sexually.

As the very image of The Madonna, The Maiden, the perpetual virgin, Immacolata is rendered vulnerable to such assaults. They threaten the very essence of the power she wields, her totemic purity. But Shadwell, being the impotent, empty creature he is, can’t even do it directly: Instead, he subtly trains Immacolata’s own nieces and nephews, the abominable spawn of her undead sister, The Magdalene, to do it for him.

The assault is one of the more horrific scenes in the book, reducing, as it does, an entity that has, theretofore, been an icon of raw, untempered power and unmitigated threat, to another victim of Shadwell and the filthy, a-poetical world he represents. This is the point the balance of power tips, and Immacolata shifts from being our principle antagonist to another example of magic, imagination and womanhood being objectified, commodified; reduced to little more than an object, by corrupt and power-hungry men.

Immacolata, as with many of the female characters in the book, runs the gamut of various archetypes of “womanhood” and gloriously lampoons or inverts them. Her interactions with protagonist, Susanna Parish, are particularly fascinating, as the two mirror each other in profound and significant ways:

During one of their early encounters, Immacolata inadvertently “gifts” Susanna a measure of the living, female power that courses through her: The Menstruum. This power, utterly lethal in Immacolata’s hands, becomes a more subtle force in Susanna’s, who uses it -and is transformed by it- in numerous profound ways. Just as Immacolata is a living mythic archetype, so Susanna is a notably real, complex, ambiguous and “impure” woman, a normal person who happens to blunder -or be drawn into- events she can’t comprehend.

Their first meeting is almost one of opposites, sisters born from different wombs, bound to inhabit contrary destinies. That Immacolata, a creature who has death in her gaze, who can unmake sanity with her shadow, doesn’t simply dispatch Susanna where she stands, is more than mere narrative convenience: It’s as though Immacolata recognises the place she’ll come to occupy in the story, and therefore has no choice but to spare her. Whenever the two meet, their interactions are rarely antagonistic; they speak as equals among vermin, as sisters that can never truly be apart again.

That Susanna is the one who ultimately emerges as the more powerful, the more triumphant, is a fascinating aspect of the story’s Feminism: Immacolata, despite being a living satire on patriarchal, mythic prescriptions of “femininity” and womanhood, can’t help but evoke those traditions by the fact of her nature. In that, she is still somewhat bound by them, simultaneously reliant on them for the opposition she embodies and rendered vulnerable to them. The text is powerfully aware of this, and so presents Susanna as a more complex, ambiguous, self-defined entity; one who doesn’t require Immacolata’s self-denial or monomaniacal “purity” in order to be powerful, to be her own species of demi-goddess.

And, ultimately, it’s Susanna who prevails.

Immacolata, meanwhile, is not only reduced and defeated; it’s her murder by Shadwell, in that most sacred state at the very heart of The Fugue, that unravels The Weave and murders Wonderland. In a bitter irony, she gets what she wants at the beginning of the book, but only after her ultimate denigration and sacrifice. Later, she is diminished to a supporting role, a phantasmal condition in which she provides warning and advice to those who were once her enemies. She is reduced from the prime antagonist of the piece to a creature of bones and dust, who can only observe and pass comment on what occurs around her.

In this, she becomes the victim of her own symbolic purity; such is never meant to sustain, certainly not in the world of ambiguities and contradictions Barker draws. And, in another bitter irony, she achieves her own standards of “purity” in death, becoming the Thanatic opposite of the problematic erotic entity she was in life.

For my part, when I originally read Weaveworld, I’d never come across Fantasy antagonists presented in this manner; with such wit and passionate intelligence, in such delirious and ambiguous terms. Shadwell’s species of banal evil contrasted to Immocalata’s mythic nature presented a dichotomy that demanded my eleven-year-old attention, and has yet to let go some thirty years later.

It’s impossible to talk about Immocalata without, of course, invoking her undead sisters. The other aspects of the ancient “Triune Goddess” archetype: The truly horrific “Magdalene,” a rapine and infinitely fecund ghost that sexually assaults its male victims and uses what she teases out of them to produce the most obscenely hideous children (a small army of monsters, born of death and horror). Once again, Barker takes the patriarchal prescription of “The Mother” and turns it on itself, producing an atrocity that fulfils every requirement thereof but in the most obscene ways imaginable.

The early sequences involving The Magdalene rank among the most graphically horrifying Barker has ever written. Furthermore, his deliberate inversions of the mythic “Mother” archetype remain shockingly transgressive to this day:

The Mother Archetype Perverted: The Magdalene

The Magdalene is that archetype personified and taken to hideous, disturbing extremes: Being undead herself, the life and fecundity tradition would have her exemplify becomes warped into a less wholesome condition. The ghost is repulsively sensual, endlessly seeking out men whose appetites and neuroses she feeds on:

For all their terror, their disgust, her victims are drawn to her and the collision of appetites and preoccupations she manifests: She is The Mother, and as such, reduces all men to quivering, needy children, causing them to regress into states of vulnerability and powerlessness where all they knew was need. She is also a walking Oedipus Complex, the maternal and the sexual repulsively intertwined: Those she assaults experience strange hallucinations of being both babies in the crib and men at their most aroused. She preys on such confusions, feeding off of them as well as whatever physical matter she takes in order to produce her curdled children.

She also manifests an inversion of standard sexual dynamics: The men she “loves” are utterly disposable, existing as potential sperm-donors and playthings, then as nothing. In that, as in every aspect of her nature, she serves as a symbolic assault on traditional, patriarchal templates of sexual relationships; any and all delusion of male power or primacy undone in her presence.

In her perpetual motherhood, she represents the redundancy of men in child-rearing, the almost useless nature of the male in family structures or dynamics (under the assumptions of patriarchy to which Barker is consistently opposed). The horror of her is therefore dense and multi-layered: In the immediate, she is stronger, more powerful and excessively lethal than any man, prone to sexual and psychological violence that markets itself as expressions of love. To men in particular, she represents a species of danger that rarely exists in horror or fantasy; one that targets us in our most sacred and unspoken neuroses, the sublimated drives and dreads that are the source of every fear and fetish.

Symbolically, she, like her sisters, assaults aspects of “womanhood” that patriarchy and tradition seek to enshrine and impose within our cultures (whether they legitimately exist or not): In her, the salubrious nature of “The Mother” is transformed into something dark, obsessive and perverse: Children are rendered into unwanted monsters, disposable and deformed creatures with patricide on their minds. Perhaps most forbidden of all: She rips the layers of scar-tissue away from our psyches, forcing us to confront sublimated concerns and unacknowledged neuroses the existence of which make a mockery of the golden carves we’ve constructed of “family.”

As a monster, she is arguably unequalled in the book (and lacks many competitors in Barker’s entire back catalogue). While there are more powerful, more destructive entities in its pages, very little is as grotesque, distressing or perverse. Furthermore, she’s a species of fascinating monster that’s also a character (when she finally meets her end, Immacolata mourns profoundly, deeply effected by the loss).

The last of the sisters, The Crone, is arguably the least and also the closest in nature to her original myth: A withered ancient, she acts as the guide and soothsayer for the trio, reading auguries in her undead sister’s afterbirth and thereby shepherding them along the appropriate path. She doesn’t enjoy as prominent a role as the others, serving more as a background character, but is essential at various key points as a vector for the plot.

Together, the sisters represent a fascinating dynamic: At once Barker’s exultation of and satire upon the traditions he derives inspiration from. None of this is made explicit mention of within the story; it’s ultimately left up to the reader to infer based on the contexts they bring to their reading. Yet they stand as among the most complex, symbolically resonant and unsettling antagonists in all of his work.

Regarding antagonists, there is one more it’s necessary to make mention of; one who occurs notably later in the plot than the rest, yet is similarly symbolic in nature:

Detective Inspector Hobart, scion of law and order. A man who believes that morality is synonymous with obedience to authority, and that anything beyond the rational, expected and prosaic is de facto chaotic, corrosive and evil. He is a man sublimely without imagination, who sees things in simple binaries: Law and chaos, black and white, good and evil. The irony of Hobart is one that lies at the heart of conservative assumptions of morality:

The world he believes in does not and has never existed. It is, in fact, as contrary to the reality of human experience as any magic or miracles he might encounter. Yet he insists on his peculiar brand of Fascistic madness as truth, absolute and unassailable. Like Shadwell, Hobart is an avatar of systemic and accepted evils; whereas Shadwell is the narcissistic vacuity of materialism, Hobart is oppressive, enforced conformity; law and order at the price of liberty.

At his entrance to the fairy tale, Hobart is a man antithetical to its thesis: He regards freedom of thought and action as corrosive deviance, ideas beyond the traditional and prescribed as cataclysmic to notions of society (which he worships with the absolutism of the religious fundamentalist).

Unlike Shadwell, however, Hobart has hidden depths:

Beneath his conservatism is a broiling mass of repression and self-loathing, a peculiarly male state of hostility that is projected outward and mythologised, whatever scapegoat he assigns assimilated into wholly paranoid narratives spun to justify his excesses and violence. In that, he stands as a perfect symbolic manifestation of moralistic Fascism, a kind that was culturally pervasive during the time of Weaveworld’s writing in the UK, and which Barker would have experienced directly as a member of London’s queer underclass.

Hobart is a poisoned chalice, a man ruined and turned against what might’ve otherwise been his essential nature by cruel and mutilating narratives of conservatism. He is law, the brutality and innate violence of police forces and the inherent danger of those who believe they have God on their side (God here serving as a metaphor for monoliths such as law, order, society, morality etc). Hobart evinces a strangely fetishised martyr complex regarding his role; he thinks of himself as having sacrificed his life for a “greater good,” as something noble and saintly, no matter the abuses and violence he sanctions.

When presented with overt evidence of magic and miracles -Raptures as wielded by the Seerkind, the Menstruum as expressed through Susanna-, he experiences something approaching a mental breakdown, unable to believe or reconcile the evidence of his senses with the narratives he’s enslaved himself to. He thus engages in an act of mythic denial, weaving the miracles he witnesses into narratives that accord with the parameters of his world-view (terrorists, hallucinogenic chemicals, some form of unprecedented, mass-hypnotic attack on British soil).

His singular obsession finds scapegoating focus on Susanna, whom he casts as the antagonist of his particular myth; a woman who embodies everything he most loathes and yet, whom he can’t exorcise from his mind (that his obsession runs beyond the antagonistic is almost certain; her status as a woman with power, let alone power he can’t define, combat or control, is more than enough to earn his ire).

The two become embroiled in a lethal game of opposing forces that swells and recedes throughout the narrative: At intervals, they are brought together in moments of incredible, dreaming intimacy, in which their mythic roles are made flesh:

Here, in the realm of dreams and stories, he imagines himself as a great dragon, a wounded, ancient and destructive entity, and she a maiden (the very role Immacolata inhabits, in her peculiar and extreme fashion).

However, Susanna breaks those prescriptions, defying those parameters too, shedding the patriarchal condition to become the serpent herself, while Hobart becomes a wounded, broken Knight, quietly pleading for his own destruction. In this, they see into the secret hearts of one another, become intimately and profoundly bound.

Hobart is a man in mourning for himself, who secretly yearns for death, and a release from the endless trials and disappointments of the world. Whereas Susanna is more attuned to her unspoken self; not at odds with it. And so, Hobart finds new reason to despise her and seek her destruction: She knows him as nobody ever has or should, as he himself is reluctant to acknowledge. Furthermore, she inhabits a state of self-knowledge and celebration that he never can, so closed off and alienated from his own secret soul.

It’s perhaps little wonder that he ultimately becomes associated with -and effectively enslaved by- Shadwell. The two symbolically represent coalitions of extremely dark forces; Shadwell the salesman, the demagogue, the populist, Hobart the police, politics and the establishment. This is Barker’s sweeping and excoriating commentary on Fascism ranged against innately human forces of imagination, connection and the shared poetry of our internal lives. It is not only trenchant and unwavering in its resolution, but has universal application (as we are all too aware some thirty years following original publication).

For a time, Hobart becomes strangely subservient to Shadwell, such that the man treats him as nothing more than a personal dog’s-body. Hobart becomes ensnared by his obsessions, the magical jacket providing him a vision of the apocalyptic fire he’s always imagined, by which he might scour the world clean.

Yet, unlike Shadwell, the story retains some measure of sympathy for Hobart: He is a man broken on the altar of his ideology and the confusions they germinate, being so at odds with the lived experience of reality. Shadwell might be empty, but Hobart is pathetic, his aesthetic performances of strength exactly that.

In the aftermath of Shadwell’s ultimate desecration (the destruction of Wonderland, and the man’s descent into fundamentalist mania), Hobart accompanies him on an odyssey across the Earth, to the most barren corners of the planet, in search of something so terrible, even Immacolata and her sisters dread it:

The Scourge.

The very scouring, heavenly fire Hobart dreamed of, a self-proclaimed angel, incomprehensible, alien and single-mindedly obsessed with the destruction of the Seerkind and all magic.

Hobart proves unequal to his own apocalyptic visions. Ultimately, the fire goes out of him the instant it enters him: He no longer wishes to be The Dragon, to author Susanna’s destruction. He becomes little more than a tormented vessel, a charred and wretched vehicle for the angel itself.

It’s a stunning symbolic examination of Fascism’s innate self-destructive tendencies; it is the fire that devours all, including its own adherents. It makes no distinction between the ostensibly “guilty” or “innocent.” It is absolute, fundamentalist certainty made manifest, the genocidal fire of a mad angel (which it proclaims itself to be).

Fascinatingly, it’s in this lost and demented entity that both Shadwell and Hobart find what they ostensibly seek: In Shadwell’s instance, a means to enact his jihad against magic (and, by extension, imagination), in Hobart’s, the very fire he’s secretly longed for and imagined wielding all his life. However, both find their expectations simultaneously fulfilled and terribly defeated:

Shadwell discovers a force he can neither comprehend nor control, that operates according to its own terrible delusions and life-scouring certainties, immune to his typical manipulations and persuasions. Whereas Hobart comes to realise how dreadful the fire he’s imagined is in reality; how it burns all it touches, including the one who wields it. Made a vessel for the self-proclaimed “angel,” he finds his body endlessly seared from the inside out, reduced to wretched meat cooked in the bone, spilling murder from every pore, yet unable to die.

This is Hobart’s ultimate realisation: Everything he ever wanted or imagined revealed as a force of mad, indiscriminate destruction, that won’t be satisfied until the Earth itself is nothing but desert and silence.

The Scourge -or “Uriel of the Principalities,” as it names itself- is Barker’s commentary on the ultimate and inevitable manifestation of Fascism, theocratic certainty and Fundamentalist absolutism: A fire that devours all, that consumes everything in its path without pause or reflection. It comes to puppet those who wield it, becoming a purpose in and of itself, and enslaves those who dream of it such that they become mere agents of apocalypse. Furthermore, it mutilates and torments its self-fancied masters as profoundly as its victims (by story’s end, Hobart is a naked mass of agonised humiliation; there’s almost nothing left of him except grief and regret).

It is the death of human imagination, of dreams, of fantasy. More terrible than even the deepest evil the Weave ever hosted, than Immacolata and her sisters, arguably than almost anything Barker has ever conceived (with the possible exception of Hapexamendios, antagonist of the epic Imajica).

Furthermore, “Uriel” itself is a victim: Not literally a biblical angel as it believes; rather, a strange, extra-dimensional entity driven mad by its isolation and spiritually poisoned by the most toxic fantasies of humanity. It believes itself an angel because of Abrahamic stories thereof; that’s where it derives its assumed name and nature from. In that, it is a devastating commentary on how powerfully stories can poison us; how certain narratives can drive us to murder, genocide and beyond.

Ultimately, it requires connection with its own strange dreams to heal itself; acknowledgement of the loneliness that has driven it to madness. Salvation is, ironically, found through the very artefact Shadwell once used to gull and seduce his victims; the magical jacket that can provide anything the observer most secretly desires. Uriel, staring into the lining of the jacket, sees an echo of itself; another entity of its kind, with which it can ascend from this lonely, desolate sphere.

In connection, togetherness, imagination, there is salvation. Even for an entity that once reflected the most profound malevolence of humanity. Only Shadwell is without any such ambiguity, and therefore any chance of redemption. Barker spares him nothing, making his ending ignominious rather than epic, as befits a creature so utterly hollow, shabby and worthless.

Stories become the salvation of all who can connect with them, such that the book’s protagonists ultimately come to live in them, to be a timeless part of them (certain images in the book suggest that time unravels and twists upon itself near the heart of the Fugue, such that our human protagonists, Cal and Susanna, were always a part of it, whether they realised it or not).

As the story promises; it is one simultaneously without beginning or end, a perpetual, mythological loop to be revisited and experienced over and over, in all its swell of metaphysical joy and depths of unfathomable horror, in all of its profundity and incisiveness and imaginative brilliance.

How can I even describe my original reading? Eleven years old at the time, I set the book down with my brain on fire, every sealed doorway burned open, every shadowed recess ablaze. I had never experienced fiction of its like, in any genre or medium. The reading of it fundamentally rearranged the topography of my mind, the shape of my imagination. I walked away from the book a profoundly different individual. In the years since, I’ve read it once a year, every year, and my appreciation has only swelled with familiarity:

Weaveworld is such that new facets and interpretations reveal themselves with every exposure. It has become a marker for me of how fiction alters as we do, no matter how well-known the subject in question. I am consistently awed by the depth of imagination and degree of craft that informs the finished work, simultaneously inspired and intimidated.

There is no doubt in my mind: Without it, I would not be who I am. I would not have ever put pen to paper, never conceived and written the stories I have. It wasn’t the beginning, but it was a quantum leap into other, more ambiguous realms.

It is, without exception or equal, among the most important, formative books of my life. Before Weaveworld, the notion of sex and sexuality being subjects to be explored in fantastical terms never occurred to me (as I’d never experienced it, outside of forays into Ancient Greek and Celtic myth). That fantasy fiction could be so innately queer was entirely beyond my contexts or comprehension at the time (and this book undoubtedly aided in my own self-realisation as a gay man). Despite most of the romantic and sexual entanglements in the book being ostensibly straight, the book itself is powerfully, profoundly queer.

Being a child and teenager of the late 1980s/early 1990s, I’d never been provided that acknowledgement or license before. While queer writers obviously existed in genre fiction, markets were such that they were generally not permitted to -openly- explore queerness itself in their work.

Then along comes Clive Barker, blasting those gates off their hinges and skinning alive their self-appointed keepers.

For the first time, I realised the true potency and potential of fantastical fiction: Not merely to entertain or provide escapist diversion, but to confront, to explore, to transform. Nothing is forbidden in that realm, as nothing is forbidden in dreams. All aspects of our experience are not only possible, but essential. Barker was the first -and remains among the few- writers in that tradition who doesn’t cleave to traditional dichotomies:

Here, there’s no distinction between the “real” and the fantastical, between dreams and waking: All exist as expressions of the other, as components in a much grander, more complex engine. Likewise sex and magic; two factors of human existence that so often sit at odds in fiction (or that bizarrely cancel one another out; the existence of one meaning the automatic rejection of the other).

Here, the two are powerfully intertwined, such that the denial or indulgence of sex and sexuality can grant or shape the nature of powers that might otherwise be denied.

The Metaphysical Anarchism of Weaveworld

Weaveworld promotes a species of metaphysical anarchism, a carnivalesque celebration of the strange and the other that’s surrealist in its Utopianism, ineffably queer in nature and implication. The condition of living dreams The Weave promises is revolutionary; a condition that will change everything, undo the evils of history and tradition and set humanity on a purer, more transcendent course.

It is a story profoundly disinterested in the conservative, “return to status quo” that so much ostensibly “straight” genre fiction champions. Here, “status quo” is not something to protect or defend; it is cancerous, corrosive, oppressive. Quietly but imminently genocidal. Revolution, renaissance, is the only way forward in Barker’s purview. The only thing that will save us. This is wholly and utterly the perspective of a queer man who has witnessed first-hand the oppressive and stunting evils of a culture bewitched by notions of tradition and conservative “morality.” The work of a man who has moved among the exiled, dispossessed and underclass of his culture and found wonders there.

And it spoke to something in me that, at the time of my original reading, was nascent, but waiting for that initial spark to light the inferno. In the years since, it has accompanied me through every evolution and transition, become a benchmark which inspires as profoundly as it intimidates.

While there are more ambitious, arguably more brilliant works in Barker’s back catalogue, there are few that have the same depth of personal resonance, and which carry the same sense of rapture in the reading.

A Sincere Hope: A Sacred Text for the Future

Weaveworld didn’t just introduce me to a new author, a fresh body of work; it changed my life in ways I can’t even begin to articulate, and can’t imagine being without. It is now so much a part of me, it is as close to a sacred text as I entertain, and it is my sincere hope that it becomes similar for those who discover it in the future.

George Daniel Lea

30-08-2025

Horror Features on Ginger Nuts of Horror

If you’re a fan of spine-chilling tales and hair-raising suspense, then you won’t want to miss the horror features page on The Ginger Nuts of Horror Review Website. This is the ultimate destination for horror enthusiasts seeking in-depth analysis, thrilling reviews, and exclusive interviews with some of the best minds in the genre. From independent films to mainstream blockbusters, the site covers a broad spectrum of horror media, ensuring that you’re always in the loop about the latest and greatest.

The passionate team behind The Ginger Nuts of Horror delivers thoughtful critiques and recommendations that delve into the nuances of storytelling, character development, and atmospheric tension. Whether you’re looking for hidden gems to stream on a dark and stormy night or want to explore the work of up-and-coming horror filmmakers, this page is packed with content that will ignite your imagination and keep you on the edge of your seat.

So grab your favourite horror-themed snacks, settle into a cosy spot, and immerse yourself in the chilling world of horror literature and film. Head over to The Ginger Nuts of Horror and embark on a journey through the eerie and the extraordinary. It’s an adventure you won’t soon forget!