The mutant vampire bounty hunter known as Durham Red is one of the most popular characters in British comics. An unsung figure in vampire fiction and one whose appeal remains truly troublesome

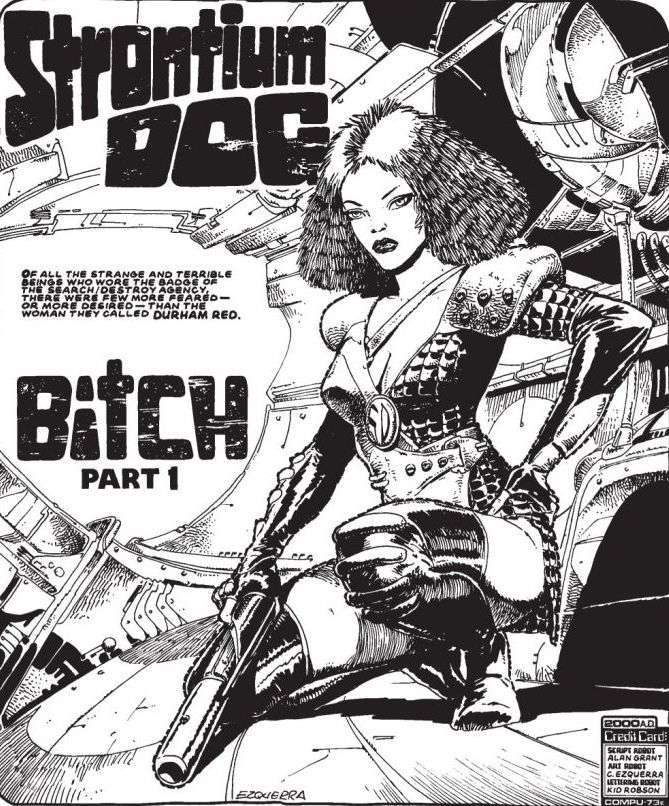

“Of all the strange and terrible beings who wore the badge of the Search / Destroy Agency, there were few more feared – or more desired – than the woman they called Durham Red.”

A suitably pulpy teaser for one of the most enduring – and problematic – characters to ever appear in still-going-strong British sci-fi anthology comic 2000 AD.

This first-page glamour shot by the legendary Spanish artist Carlos Ezquerra makes the ‘desired’ bit pretty obvious. This was back in 1987 when 2000 AD was still targeted pretty much exclusively at British teenage boys who had to make do with hedge-porn and the underwear section of the Kay’s catalogue. But this mutant vampire bounty hunter – with her sour cherry pout and a hairdo like a Norfolk cottage – doesn’t look any more fearful than all the other ‘strange and terrible’ scuzzbags who populate the mutant-ridden universe of Strontium Dog, the intergalactic Spaghetti Western strip in which Durham Red first appeared.

You had to read on to realise what it was about Red that made her so frightening. The character’s darkly seductive appeal plunges much deeper than that formidable cleavage, a scariness that runs vein-deep and assures the character an undeniable yet unsung place in the wider canon of vampire fiction.

I started writing 2000 AD’s current revival of Durham Red (with immaculately slick artwork by Ben Willsher) back in 2017, her first ongoing series for more than fifteen years. I read pretty much everything she’d ever appeared in, from those early Mandalorian-type manhunts to her muddled middle-period tales from the ‘90s when 2000 AD itself was undergoing a bit of an identity crisis. But for all her adventures, the grist of Red’s vampiric nature had, I felt, been the least explored aspect of her character.

[insert ‘4. Red shooting’ and add caption ‘Art by Ben Willsher’]

Dan Abnett and Mark Harrison did fine work weaving vampire symbology into their very-far-future space opera sequel in which Red becomes a mutant messiah, but I had my sights set on something smaller, more personal. I wanted to know what effect all that bloodletting might have on Red as a person. I didn’t want her fangs to be just another tool in her bounty-hunting arsenal, alongside her NOS-4-R2 Multi-Round Blaster and thermonuclear sex appeal.

It would take a lot to convince me that Red’s co-creators John Wagner and Alan Grant – two more bona fide legends of the British comics biz – had much in the way of subversive political commentary in mind when they created the character. Until the hot young likes of Grant Morrison barged in and started turning over tables a few months later, 2000 AD usually got by every week surfing trends in the news and (mainly American) pop culture.

Tom Holland’s popular vampire flick Fright Night had just scored a hit in movie theatres, relocating your classically charismatic vampire lord in suburban California, and the movie reached the UK in April 1986. Now if comics-creation schedules then were anything like what they are now, I’m guessing that’s exactly when Wagner and Grant would have been coming up with ideas for pitching Red’s debut in Strontium Dog. And, as seasoned comics pros, they knew a good zeitgeist when they saw one.

John Skipp and Craig Spector’s influential vampire novel The Light At The End was published the same year, while Anne Rice was busy publishing her first two follow-ups to Interview With The Vampire. The hunger for vampire stories was rising and there was certainly blood in the cultural waters. By 1987 President Reagan finally made his first public speech on AIDS, while activist Larry Kramer had already founded ACT UP, a direct-action political group that successfully pressured government, religious and health institutions to act and protect those at risk of HIV.

“Prosperous America of the 1980s denied the reality of AIDS, locking its doors against victims of the plague, while monstrous images popped up everywhere in its collective dreams. The landscape of popular culture was awash with sanguinary themes as never before.”

The Monster Show: A Cultural History of Horror by David J. Skal, 1993

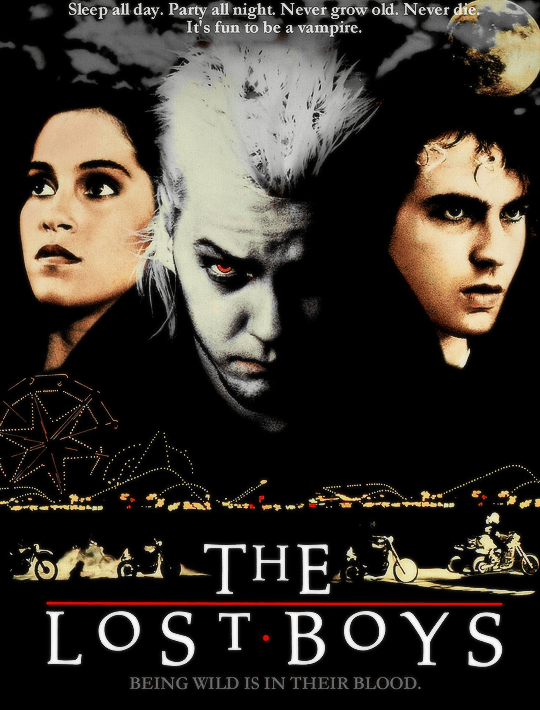

The Lost Boys and Near Dark – those other two fondly-remembered movies of the mid-80s vampire renaissance – hit theatres in the UK several months after Durham Red’s debut in 2000 AD #505 in January 1987. If vampires could be found lurking on Californian beaches and deep in the dust of Texas, then why not outer space?

Red was introduced as a sexy sidekick and moral foil for Strontium Dog’s stoic hero Johnny Alpha. Wagner and Grant announced her debut with the series subtitle, Bitch.

Okay.

According to a 2014 report by Wired and Vice journalist Arielle Pardes, the word ‘bitch’ unsurprisingly crept into common usage not long after women won the right to vote. It surged in use during the post-War years to describe any woman perceived as treacherous, ruthless, devious, promiscuous, and daring to want things her own way. All such traits describe Red perfectly.

“You’re wearin’ the badge. You’re a Strontium Dog, too!”

“Not dog… Bitch! Now move!”

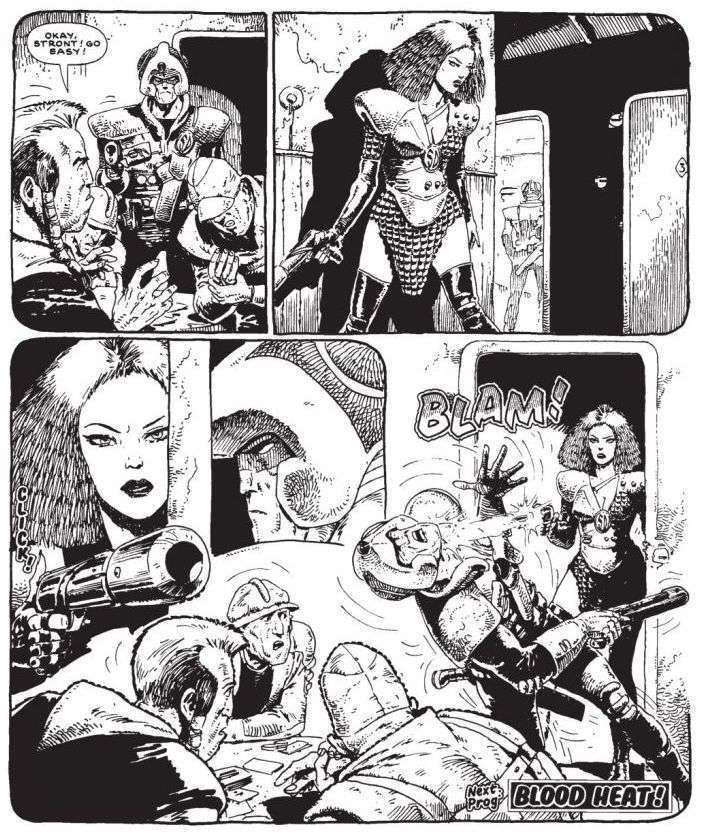

You have only to gaze into those hooded eyes to see that Ezquerra brought more than a little Lauren Bacall to his Durham Red. A beguiling monster, Red was clearly conceived as a Vivian Sternwood to Johnny Alpha’s Philip Marlowe, a literal vamp, a femme fatale, that other post-War expression of male terror in the face of female power.

Wagner and Grant certainly tapped all the right archetypal veins, and I’m sure there’s an article on a comics newsite somewhere heroically arguing Red’s debut Bitch was a consciously brave attempt to reclaim that troublesome word. But I seriously doubt any thought into it beyond the fact that a female Strontium Dog was considered a novelty worthy of a sassy title.

The series itself is a memorably tongue-in-cheek caper in which Johnny teams up with Red to rescue President Reagan from a group of alien terrorists. It’s as knowingly playful as it sounds, with Red flashing flesh and blasting bad guys, constantly hankering for a nibble of Alpha’s neck and growling come-ons like, “What do you say, Johnny? Care to indulge in a bit of transfusion?”

Red establishes herself as a cold-blooded mercenary with little time for Johnny’s sanctimony. But what’s so striking about her in this debut strip – compared to all her later incarnations, including my own – is just how sadistic she is.

She double-crosses Johnny in an early scene, stealing a bounty, only for hunger to get the better of her as she tells the poor terrified schlub to start running…

“The taste of fear… that was how she liked them best.”

Johnny finds her glugging on her exhausted victim in an alleyway. Drawing his pistol, he tells her that’s enough.

“No, Johnny,” she gasps, ecstatic. “It’s never enough!”

That, for me, is Durham Red: agent of the justice, yet angel of death.

“All three had brilliant white teeth that shone like pearls against the ruby of their voluptuous lips. There was something about them that made me uneasy, some longing and at the same time some deadly fear. I felt in my heart a wicked, burning desire that they would kiss me with those red lips.”

Dracula by Bram Stoker, 1897

Life (that is, sex) and death have always been the troubling paradox at the heart of the vampire’s appeal.

Like those three vampire brides preying on a perplexed Jonathan Harker in Dracula’s boudoir, the vampire appeals to sex drive and death wish simultaneously. The vampire is alive yet dead, beautiful yet monstrous, enviable yet damned, Eros and Thanatos combined. Indeed, “There are few more feared – or more desired.” What beautifully problematic characters vampires are.

This provocative ambiguity is exactly what vampire characters need to sustain themselves within their own stories.

After the shimmery romance of Twilight and The Vampire Diaries and the tomfoolery of Hotel Transylvania and What We Do in the Shadows, it’s somehow shocking to be reminded by monster movies like Renfield and the excellent TV adaptation of Interview With The Vampire that the archetypal vampire is a complete and utter bastard.

In Born Bad, our first series of the Durham Red revival, Red has become a victim of her own monstrous reputation. With the Doghouse disbanded and its mutant bounty hunters scattered about the stars, few are desperate or crazy enough to want to hire her. She’s now a social pariah reduced to working the door incognito in a backwater bar, struggling to make a living. Wearier and wiser, she tries to prey only upon those she feels deserve it. And yet she knows that her irrepressible hunger possesses no such moral boundaries.

[insert ‘6. Born Bad Page One’ with caption ‘Art and colours by Ben Willsher, letters by Ellie De Ville’]

In our second series, Served Cold, Red has been captured by the galactic authorities for slaughtering innocents while in the throes of the red thirst. We find her in a holding cell awaiting a death sentence that even she feels is well-deserved.

Retribution of a different sort arrives in the form of a unit of mercenaries led by a mysterious paymaster, who lay siege to the arctic custody station where Red is being held. Now she must co-operate with jailors and fellow convicts alike if they are all to survive. And, yes, I was doing a Rio Bravo with this one.

In writing Durham Red I don’t ever want a cop-out. I want Red to have done dreadful things. I want her to know that she will go on doing dreadful things, and – worst of all – know that doing dreadful things is when she feels most alive.

If only Red could enjoy the moral liberty of a John Wick, destroying endless, faceless henchfolk with the relentless ingenuity of a Jackson Pollack attacking tins of paint. Or like the gamer plunging through a first-person shooter, toggling between 9mm and 12 gauge weapons just to see the difference in damage they can do to NPC anatomy.

Violence, force, menos is one of the most primal, cathartic joys of visual media, whether it’s seeing your culture hero vanquishing a Grendel or watching the bully finally get their arse handed to them. Violence possesses a terrible magnetism, dreadful yet liberating. With Durham Red I’m happy to indulge the reader in the pleasures of the kill – within the safe space of melodrama – but I aim never to let them go without a smear of ugliness, just a smudge to remind them of the cost to one’s soul of drinking too deeply.

The notion of violence without cost is a lie. Ask any veteran, any first responder. It’s a lie commonly sold to us by corporate IP-holders and social media vendettas. And it’s a lie of which we must be aware.

Why do filmmakers abruptly slow down an action scene mid-flow if not for us to savour the abstract pattern of plasma globules sputtering from a bad guy’s artery? Why are we seeing this if not to enjoy it, to relish it without cost to ourselves?

Sating a reader’s own vampiric bloodlust without restraint or caution is a criticism that was often levelled at the Conan-derivative heroic fantasy novels of the 1970s, too many of which pandered to a reptilian lust for carnage and sexual violence.

“Unfortunately, the majority of imitators who came in recent years to fulfil the demands of publishers sensing a commercial market were attracted to what is presumably a compensatory fantasy of homicidal barbarians and grunting rapists. As a result, they produced characters even more terrifyingly simple-minded than Conan himself. The appeal was never easy for me to understand, but I was given a clue some years ago when, as a guest of a fantasy convention, I appeared on a panel with a group of sword-and-sorcery writers who told the audience that the reason they wrote such fantasy was because they (and, they implied, the audience) felt inadequate to cope with the complexities of modern life. ‘Where today,’ asked one, ‘can you put an arm hold around a man’s throat and slip a knife into him between the third and forth ribs and get away with it?’ The answer was, of course, that the Marines were still looking for recruits.”

Wizardry and Wild Romance by Michael Moorcock, 1987

I often sense the same dishonesty at work in the broader popularity of the ‘Slayer’ archetype, those full-time vampire killers and monster hunters like Blade, Buffy and Geralt of Rivia who ply their lethal trade on whatever ‘othered’ species the story has qualified for extermination. These guys are generally untroubled by the annoyances of remorse, their worldview crystal-clear and binary, spitting lead and twirling steel with aplomb, and looking fabulous in leather while doing it.

Lest we forget that the self-styled “hunters” of the Nazi Einsatzgruppen enjoyed exactly the same fantasy.

Zombieland (2009) is just as much fun as Dead Island and every other zombie-centric FPS, and yet indulges precisely the redneck free-for-all that George Romero warned us about in his original Dead trilogy.

For me, wish-fulfilment must come at a cost or else risk failing as drama.

“Sleep all day. Party all night. Never grow old. Never die. It’s fun to be a vampire.”

Thus went the tagline for The Lost Boys, but – in story terms – it’s a party without life and soul. I prefer stories with balance, that delicious tension between gratification and loss.

My Durham Red was directly influenced by an essay written by the brilliant critic and Anno Dracula author Kim Newman for Gizmodo.

“Lestat only kills murderers — or did after Anne Rice changed her mind and decided she liked him more than whiny Louis. Edward Cullen and gang are ‘vegetarians’, which means they feed off animals. Angel seems to subsist on donor blood. The vampire leads in Being Human and True Blood are mostly on the wagon, except for flashbacks — they do sexy drinking, but have sworn off killing people… These characters get all the cool parts of being a vampire — living forever, hot girlfriends or boyfriends, stylish wardrobe, super-powers, etc — but are let off the repulsive, evil or wretched side of the lifestyle. In the end, that’s a cop-out: if they don’t kill people, or at the very least hurt the ones they love, it’s not that they aren’t proper vampires, it’s that the authors are ducking out of moral complexity in order to have a high old time without giving the Devil his due.”

Why Are So Many Vampire Stories So Weak? by Kim Newman, 2012

Newman shares my distaste for vampire tales that are pure wish-fulfilment. For me, it’s like playing a game on God Mode. I want Red to be constantly struggling to balance the scales, weighing up the cost of her actions. She’s never safe, always hungry, always moving, a shark. She’s just trying to survive and do more good than bad. She’s a force for justice, but cross paths with her at your peril.

Durham Red is not a role model, any more than her 2000 AD stablemate Judge Dredd. Both are paradoxical, heroic yet monstrous, deeply problematic, requiring the reader to know irony when they see it. That conflict is the engine that drives those characters.

“All drama is conflict. Without conflict, you have no action; without action, you have no character; without character, you have no story.”

Screenplay: The Foundations of Screenwriting by Syd Field, 1979

When telling the story of any character – bloodsucker or not – it always helps to find that inner turmoil and embrace the deeply problematic.

This essay was first published on Agent of Weird: Exploring the Write Fantastic, a regular newsletter for anyone who craves a deeper understanding of horror, fantasy, dark sci-fi and every slippery subgenre in between.

It’s written by Alec Worley, the grizzled author of stories for John Carpenter, Warhammer, Star Wars, Judge Dredd and a bunch more.

If you create (or want to create) comics, prose, screenplays, or psionic thought-dramas for the pixies that live in your head, you’ll find something here that’ll help you develop your craft, understand your genre, and make you realise that you’re probably not doing things quite as badly as you think.

Your FREE subscription gets you a new essay every month, as well as easy access to the full archive of previous posts. A grimdark dungeon of insights, interviews and inspiration!

- Durham Red: Born Bad is available as a digital-only trade, and includes two seasonal one-shots.

- Durham Red: Served Cold ran for twelve episodes from 2000 AD #2212-2219 and #2221-2223, December 2020-March 2021

- Durham Red: Mad Dogs is currently running in 2000 AD and began with issue #2326.

Finally, a HUGE thank you to Jim Mcleod at Ginger Nuts of Horror.

Alec Worley

Alec Worley is an award-lacking author from South London. He writes comics for John Carpenter and 2000AD (home of Judge Dredd), as well as prose and audio for Warhammer. He tries to sound all clever by writing essays for his FREE Substack newsletter Agent of Weird: Exploring the Write Fantastic. You can find out what else he gets up to in the worlds of horror, fantasy and dark sci-fi by visiting his website. Oh, and you can check out his LinkTree for everything else.