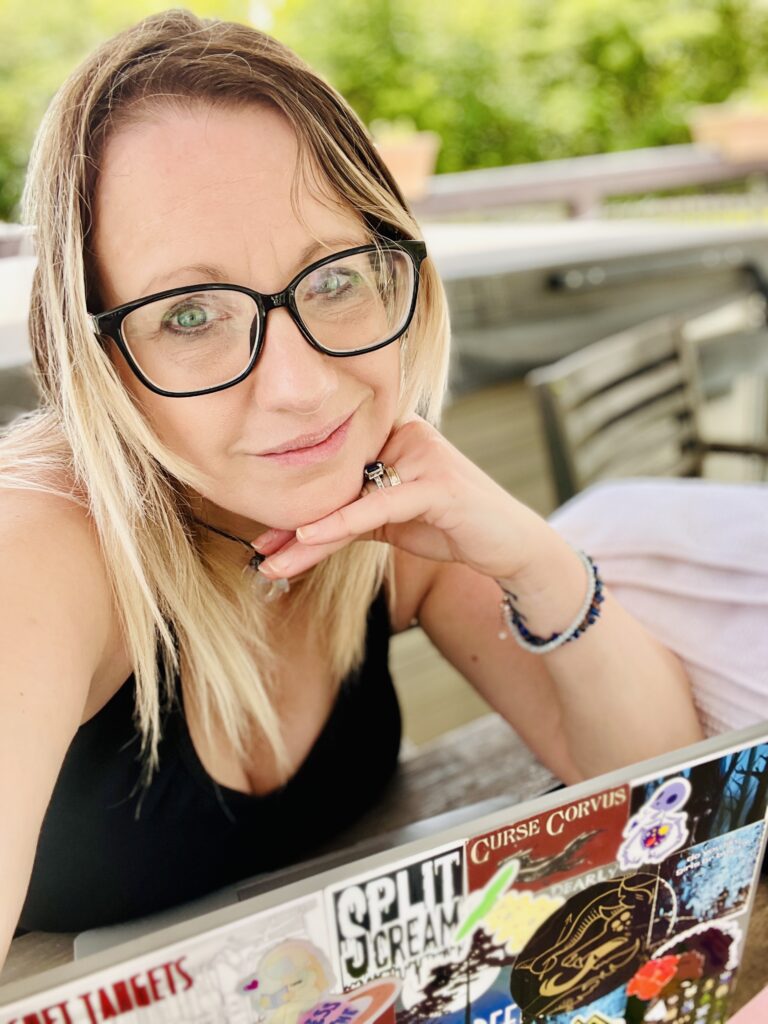

Elizabeth Broadbent

Elizabeth Broadbent left the South Carolina swamps for the Commonwealth of Virginia, where she lives with her three sons and husband. She’s the author of Ink Vine (Undertaker Books), Ninety-Eight Sabers (Undertaker Books, 2024) and Blood Cypress (Raw Dog Screaming Press, 2025). Her speculative fiction has appeared with HyphenPunk, Tales to Terrify, If There‘s Anyone Left, Peunumbric, and The Cafe Irreal. During her long career as a journalist, her nonfiction appeared in places such as The Washington Post, Insider, and ADDitude Magazine.

WEBSITE LINKS

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/writerelizabethbroadbent

Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/eabroadbent

TikTok: https://www.tiktok.com/@eabroadbent

Threads: https://www.threads.net/@eabroadbent

Website: https://www.writerelizabethbroadbent.com

Goodreads: https://www.goodreads.com/author/show/1929656.Elizabeth_Broadbent

Could you tell the readers a little bit about yourself?

I’m a diehard swamp witch transplanted from South Carolina and adjusting to life in Richmond, VA with my three kids, two dogs, two cats, and very patient husband. I was a journalist for over a decade until I turned to fiction again.

I realized there was a market for some of the weird speculative poetry I wrote, so I tried some spec short stories. I wrote “Questions A Man Ought Not to Ask,” which was picked up and eventually republished in The Black Beacon Book of Horror. It was the first story set in Lower Congaree, where my novellas Ink Vine (Undertaker Books) and Blood Cypress (Raw Dog Screaming, 2025) and my novel Ninety-Eight Sabers (Undertaker Books, November 29) take place, along with the other books in my four-book deal with Undertaker (The Swamp Child, Bluefeather, and an unnamed YA novella).

I’m autistic, and as a child, did what we’d call maladaptive daydreaming (as a writer, we’d call it “world-building”). Because my settings tend to be so nuanced, I don’t like to leave them behind, and they weave into a larger pattern. So I have one world for my Southern Gothic, and one for my sci-fi.

Which one of your characters would you least like to meet in real life?

I definitely don’t want to meet the three men in Ninety-Eight Sabers. They utterly terrify me. They’re based on the Mirrored Men, a cryptid first reported by Derrick Hayes on the podcast Monsters Among Us. There are mornings when I go for a run and shudder thinking about them, I swear.

Other than the horror genre, what else has been a major influence on your writing?

Southern Gothic is a huge influence. I read Pat Conroy’s The Prince of Tides when I was eleven. I didn’t realize you could put words together that way. Conroy’s a popular writer, but he doesn’t get enough credit outside of South Carolina for his rich prose. I didn’t grow up in a house that kept poetry or Shakespeare. I had Pat. And when I read his book, I thought, I want to do that when I grow up.

The term horror, especially when applied to fiction, always carries such heavy connotations. What’s your feeling on the term “horror” and what do you think we can do to break past these assumptions?

“Horror” is something we shudder away from. The public associates it with blood and guts, because that’s the most palatable horror to imagine. It’s far worse to contemplate psychological horror: abuse, the return of the past, the uncertainty of the afterlife, death itself. I always tell laypeople I write “Southern Gothic” rather than use the h-word—in the urban South, that opens doors rather than slamming them shut. If I say “horror,” I’ve learned, smiles turn overly polite very fast. As a neurodivergent person moving through neurotypical spaces, you learn to adapt to these things quickly.

A lot of good horror movements have arisen as a direct result of the socio/political climate, considering the current state of the world where do you see horror going in the next few years?

I see it becoming more queer and marginalized. I imagine (hope for) more of it coming from the global South and the global majority. I imagine it becoming more neurodivergent. As we see more marginalized people finding their voices, we see them shining light on the very real horrors they’ve suffered, and many times, the best way to engage with those horrors is through speculative fiction.

Given the dark, violent and at times grotesque nature of the horror genre why do you think so many people enjoy reading it?

I have an essay I wrote for Becky Spratford about horror and child abuse and Southern Gothic that deals with this. Speculative fiction gives us a lens to look askance at true-life horror we can’t bear to engage with. We can keep real life at a distance while we look sideways.

What, if anything, is currently missing from the horror genre?

We need more openly neurodivergent voices. Full stop. We need more authors who are willing to openly discuss what neurodivergence means for their fiction and their stories, and the ways they tell their stories and interact with the publishing world. We also need to take a hard look at making publishing more accessible for ND authors.

What new and upcoming authors do you think we should take notice off?

Rebecca Cutbhbert has a new collection that came out October 5, Self-Made Monsters. It’s a stellar exploration of feminist horror in lush, rich prose. I was lucky enough to read an early copy and I’ve been obsessed ever since. Her stories about trees in particular hit me hard.

Are there any reviews of your work, positive or negative, that have stayed with you?

I’ve been a huge fan of L. Marie Wood since I read her book, 12 Hours, a novella in the same series as Blood Cypress (I went, Oh God, Jennifer Barnes put my book in the same series as this?!!). She’s incredibly kind and supportive. When Ink Vine came out, she gave it a four-star review, and said the writing was beautiful—I was really touched but I won’t lie: she’s one person whose opinion meant so much to me, and I wanted to do better. I asked her to blurb Ninety-Eight Sabers. Along with a rave email, she sent back a fabulous quote which dissolved me tears:

“Ninety-Eight Sabers is a wild ride. Rich with history, small town idiosyncrasies, and thinly veiled racial strife combined with a healthy heaping of familial obligation with a side of ghosts upon ghosts upon ghosts upon ghosts upon ghosts, this tale brings to light the patina that stains the neo-South. Gracefully sown and lyrically rendered, Broadbent’s Sabers is distinctly and comprehensively beautiful.”

That meant more to me than I could possibly put into words.

What aspects of writing do you find the most difficult?

Action is the most difficult for me. I’m so into language, character, and dialogue that I tend to elide it; I have to go back and beef it out in the editing stages every time.

Is there one subject you would never write about as an author?

I have a huge cannibalism squick—I read Alive when I was eleven, too. You’ll never find people eating one another in my books, at least not graphically. Hannibal was a hard watch for me.

Writing is not a static process, how have you developed as a writer over the years?

I was a journalist with bylines in The Washington Post. I’d won numerous awards for my fiction during my MFA. When I started writing speculative fiction a few years ago, I faced rejection after rejection. I went, oh no, I really have to up my game if I want to succeed here. This is where all the cool lit fic kids went. I finally found them. So I spent a long time really working on craft. And I did up my game, and it paid off. But I had to work hard to succeed.

What is the best piece of advice you ever received with regards to your writing?

Every day. Just do it. You have to wake up, you have to write, and you have to do it over and over and over even when you’re sick of it. I write every single day for hours.

Which of your characters is your favourite?

Sullivan from Ninety-Eight Sabers right now. He’s a familiar hot mess, and my kind of hot mess. We have a lot of the same problems, and we react to things in similar ways.

Which of your books best represents you?

I wrote Sabers while I was homesick. We had just moved from South Carolina to Virginia, and I was grappling with that homesickness. How can you miss a place that’s so objectively terrible? How could you yearn to return to a home that’s soaked in blood and repugnant history? I think, in part, Sabers comes from that.

Do you have a favorite line or passage from your work, and would you like to share it with us?

One, from Ninety-Eight Sabers, I think of every single time I take the interstate back to South Carolina: “Exits passed, their names heavy with skirmishes fought, towns settled, blood shed. Too many carried history, ancestral or personal. Sullivan took the worst of them, the one that led him home.”

I tear up every time I remember that line and turn down that exit.

Can you tell us about your last book, and can you tell us about what you are working on next?

Ninety-Eight Sabers is a Southern Gothic novel about a plantation wedding destination with all the attendant paranormal mayhem of Skinwalker Ranch. They’ve brought in reality TV, and when death forces a clan of cousins to reluctantly return, producers want to turn them into witchy Kardashians with a Southern drawl. But their fighting’s making the high strangeness strangeness…

Sabers is traditionally Gothic in the sense that it grapples with the ever-present past and the ways in which history, both ancestral and personal, returns to destroy us. It grapples with race and class and gender. I was so homesick when I wrote that novel, and my own father had just died. It’s an attempt at exorcism as much as it is art.

Right now, I’m writing a novel called Bluefeather, which examines Southern gender roles through the lens of a Murdaugh-like family. That case was really close: my best friend worked (in another capacity) for Alex’s attorney, Dick Harpootlian; my husband taught kids who testified during the trial. The hyper-locality of South Carolina means everyone’s somehow involved.

If you could erase one horror cliché what would be your choice?

I adore Tom Piccarilli to the moon and back; let me start there. He’s one of my all-time favorites. But I was so depressed to see his representation of autism. I know it was the early 2000s, and at the time, I wouldn’t have blinked. But we haven’t come much farther than that. Please stop vilifying the neurodivergent.

What was the last great book you read, and what was the last book that disappointed you?

My last favorite was Piccarilli’s A Choir of Ill Children. What a masterpiece. It deserves to be up there with the greats of Southern Gothic. Just an absolute beauty of a novel, start to finish. Piccirilli’s prose is stunning.

Disappointment? The Midnight Road, where the villain turns out to be a gross misrepresentation of autistic person. I was so sad, because I loved the book otherwise, and I love Piccirilli. But the book is a representation of the time, and he was working with the information he had available. I don’t think it’s fair to demonize him for it. I try to look at it as a time capsule. It’s not okay. But I’m not going to hold him to the same standard I’d hold an author in 2024 with all the diagnostic and liberation material available.

What’s the one question you wish you would get asked but never do? And what would be the answer?

What can we do to make publishing more accessible to neurodivergent authors, specifically those for whom social interaction is taxing and fraught with minefields?

I don’t know the answer to that. I know we need ND voices to be louder and more active in advocating for our needs. StokerCon having time-out rooms was a step. But we need more awareness that, say, for autistic people, social hierarchy is a foreign concept. And I don’t know how we get there.

Ninety-Eight Sabers by Elizabeth Broadbent

Family secrets. High strangeness. Reality TV.

The Trenholm clan helped found Lower Congaree, South Carolina. Their land is cursed. Their abusive patriarch has croaked. Only heirs who attend the funeral will inherit.

But when Truluck Trenholm suffered his eventually-fatal stroke, oldest son Ash turned the haunted plantation into an enormously successful reality show—with all the attendant ethical issues of profiting off its legacy. Forced to tolerate the intrusion of California producers, grip guys, and cameras, toting a ton of childhood trauma, Ash’s brother and cousins have plenty of animosity for each other, along with a strong aversion to the paranormal shenanigans of their childhood home. But when Truluck’s funeral goes pear-shaped and the cousins are cut out of his will, Hollywood producers offer the deal of a lifetime: they’ll turn the Trenholms into witchy Kardashians with a Southern drawl.

If the cousins walk away, they’ll lose everything. But the farm’s high strangeness keeps getting stranger. Something’s happening on Cypress Bend. And filming might make it worse…

Combining the literary tradition of William Faulkner, Michael McDowell, and Octavia Butler with the shimmered lunacy of John Berendt’s Midnight in the Garden of Good and Evil, Elizabeth Broadbent’s Ninety-Eight Sabers is a Southern Gothic novel about a family determined to stick together as history threatens to tear them apart. This is a book that asks how we live with the past—and how we accept our responsibility for it in the present.