Good Madam (Mlungu Wam), 2021, directed by Jenna Cato Bass

Released as a Shudder Original

Officially apartheid ended in 1994: an open election was held on April 27, a new flag was raised, and South Africa became a free and equal nation.

Or, to put it another way: apartheid is a living memory, and there are people who have spent more of their lives under its boot than they have in the time after. Whether you’re a nation or a person, that’s not something you just dust off your skirt and walk away from.

Tsidi is a single mother living near Capetown, and she’s not living a free and equal life. She’s doing her best, and she’s far from cowed: she’s responsible and clear-sighted and quite willing to get into a confrontation – but when you don’t have any power that doesn’t usually do you any favours. Tsidi used to live with her beloved grandmother, but now she lives nowhere: her grandmother has died and the house they shared is a family property, and the new family elder declares that Tsidi and her daughter Winnie will have to share it with Tsidi’s brother Toto.

Tsidi and Toto clearly don’t get on – in fact, Tsidi doesn’t get on with anyone in her family now her granny is gone: she wants to make her own decisions and raise her daughter as she sees fit, and her surviving family are old-fashioned about women who act that way. Rather than submit, Tsidi leaves – but where can she go? She’s no longer with her ex and he’s moved on to other women; she doesn’t own anything.

Good Madam (Mlungu Wam), 2021, directed by Jenna Cato Bass

That leaves one option. She can go to the mother – a live-in housekeeper for a white woman called Diane, and who is a better servant to ‘Madam’ than she ever was a mother to Tsidi.

Tsidi and Winnie set off. Winnie likes the new place: it’s big and beautiful, far nicer than the poor conditions her father has in his home in Gugulethu – and Winnie is facing the temptations of disloyalty to her own culture. She’s at a school where she makes white friends, her Xhosa conversation drifts into English more often than Tsidi’s, and every sweeping shot over the pretty houses of the white areas and the tin roofs of the black ones reminds us just who still has the money in this country.

Mavis, Tsidi’s mother, is willing enough to take them in, but the rules are clear: as Winnie sums up: ‘We should pretend not to be here.’ This is Madam’s house, even if Mavis has lived and worked in it for decades – and even if Madam has sunk into such a state of ill health that we never see her, only the loom of a staircase leading to a room Tsidi and Winnie may never, never enter.

All isn’t well in Madam’s house. Malign spirits are at work. Secrets lurk. Mavis is stoical and insists that everything’s fine and anyway, ‘I have no right to just do what I want,’ but this is not a safe home for three generations of Xhosa women.

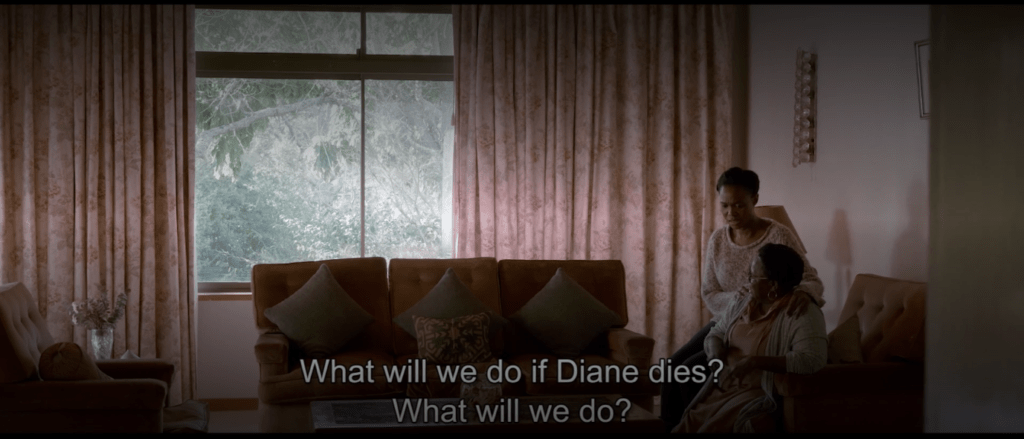

But what are they to do? As Mavis points out, ‘Without Diane home I’ll have nowhere to go.’

A bit of a disclaimer

Most of the dialogue in Good Madam is in Xhosa, which I do not speak. Jenna Cato Bass is a white South African who co-wrote with assistant director Babalwa Baartman and star Chumisa Cosa, so if you happen to speak Xhosa then you can fill your boots on the actual film and skip to the next section of this review.

For those who don’t, let me lay out a few basics that confused me until I got a grip on them, because how people address each other in this film might lead an English speaker to mix characters up – at least it did me, though admittedly I’m bad with names. ‘Mama’ can mean either ‘Granny’ or ‘Mum’. ‘Sisi’ seems to be a term for any female relation regardless of age – you can call your mother or your daughter ‘Sisi’ just as freely. Tsidi (short for Matsidiso) is sometimes addressed by her family as ‘Mam’Tshawe’, which I’m guessing refers to the fact that she’s a mother – I know that in Shona you can address someone as ‘Amai So-and-so’ meaning ‘So-and-so’s mother’, but that’s a different language, so that’s as much as I know. Keep your eye on the context.

The names you need to keep a grip on are: Mavis, the grandmother; Tsidi, the mother; Winnie, the daughter; Luthando, Winnie’s dad – and Gcinumzi, Mavis’s son who she let ‘Madam’ Diane adopt and rename Stuart. Also, if you don’t know the insult ‘coconut’, it’s a way of calling someone brown on the outside and white on the inside, and the fact that Gcinumzi/Stuart only ever speaks English to his family is one demonstration thereof – though this is not the most horrific of his misdeeds, as it turns out.

If you are smarter than me you may not need this explanation, but the film is good enough to deserve your full attention, especially in the first act, so let’s try to minimise distractions.

Also: this is a film where the goodies are black and the baddies are white, and if you can’t put up with that then feel free to shoo.

Manual labour

This film is an international collaboration; particularly exciting if you’re me is that one of the co-producers is Kristina Ceyton, who also produced Jennifer Kent’s masterpieces The Babadook and The Nightingale. And there is a clear connection here: you can see why Ceyton was excited about Good Madam, because Bass and Kent share a bone-deep fascination with the life textures of powerless womanhood – and in particular, the labour of powerless womanhood.

The deepest horror in this movie is a kind of soft-grinding relentlessness. Mavis is present in conversation, but her real presence is her hands: shot after shot of her scrubbing, chopping, stirring, rinsing, repetitive action after repetitive action maintaining a pristine home she doesn’t own. The first image of the film is a drain, and over and over we see swirling circles: soap in water, pots of food, washing machines, a visual reminder of how the work goes on and on and never reaches a stopping point that becomes so vivid and imposing that the biggest ghost in this film is really the labour itself. The sound design supports this marvellously: endless moments of soft grinding like a whisper of alienation. This isn’t Tsidi’s home. Mavis is Diane’s maid before she’s Tsidi’s mother – and that’s not an absence, it’s an ever-present activity.

Good Madam (Mlungu Wam), 2021, directed by Jenna Cato Bass

If you’re a fan of the The Babadook this will be familiar: Bass captures the unassuageable demands of domestic labour just as Kent captures the unbroken exhaustion of motherhood. And Bass’s camera is an intimate one: when we see faces, we’re crowded up to them as if we were a member of the family right there in the mix, always a slightly different height from whoever we’re listening to so our perspective feels human rather than omniscient. Possessions loom large in shot after shot: all the knick-knacks Mavis has to clean, the African art Diane displays (for dusting by her African maid, of course), the cups Mavis is or isn’t allowed to use depending on whether or not they’re Diane’s.

Really, the set-up is one of the most potent I’ve ever seen. Tsidi is desperate to connect with Mavis, but all she knows how to do is point out what Mavis is resolute in denying: that Diane has Mavis ‘living under apartheid’. Of course Tsidi’s heart is broken – but as the film goes on and Mavis unbends a little, we start to see the other side of it. Mavis grew up under apartheid; she was a housekeeper; now she’s old. Her choices are endure it patiently, or find herself in a life even less endurable. If Tsidi’s a better mother – and she is, she’s good with Winnie – well, she didn’t have to spend the prime of her life under apartheid. And even Tsidi has nowhere else to go.

Sticking the landing

‘What would horror look like if it happened to the people who actually experienced it on a daily basis?’ Bass mused in an interview with Variety. ‘How would horror change if you took away those fundamental things that we expect … the fact that horror is a sort of visceral, voyeuristic thrill … about people who don’t experience horror [in everyday life]?’

Well, that’s the question, isn’t it? And Good Madam does wonderfully in conveying the horror of Mavis and Tsidi’s everyday life: it’s subtle, and it’s pervasive, and every frame of it is absolutely haunted.

And I hate to say anything negative about such an achievement, so I’ll say to begin with that just for the domestic horror alone, Good Madam is absolutely worth a watch.

But Bass, by her own account, isn’t a big fan of horror. Let’s not gatekeep: some extremely interesting work can be done within a genre by people who bring a fresh pair of eyes, and you don’t have to have watched all the standards to be allowed to try your hand. That’s a silly attitude. In another interview, Bass and Baartman observed, ‘We used both expected and unexpected tropes to constantly keep people feeling like they aren’t entirely sure what kind of horror film they are watching.’ That’s pretty cool – and the more conventional horror shocks land very hard, at least at first. There are some really disturbing moments that would feel right at home in a more traditional horror movie.

It’s also cool that Bass and Baartman in the same interview credit the entire cast as co-writers: a lot of consultation and workshopping happened, and you can feel it in the vividness of every character on screen. These people live and breathe; they’re densely present in every moment. And in a collaborative art like film, it really is good to see people try to reach beyond the hyper-individualistic One Great Artist myth and work for something with a strong sense of community in its creation.

But if Good Madam has a flaw, it’s that it has a certain . . . made-by-committee feel in its plotting that leaves the ending feel a bit unsatisfying. To deliver on an emotionally difficult story, the horror itself needs a strong through-line, and this movie feels a little bit lacking in the obsessiveness needed there.

I’ll drag in The Babadook for comparison, which is not fair of me because I love The Babadook so much I take it personally, but it is a way to illustrate what I mean. In The Babadook, protagonist Amelia is facing an individual problem: she is a traumatised widow with a difficult son, and she is losing the battle to do a good job with him. Surrounding her is social horror: she has slipped down from the middle class comforts of her sister into a life where both work and home is one long lonely nightmare of caring duties, and nobody will help her, and when she tries to reach out she gets that look from everyone. Oh boy, that look.

That concerned, politely appalled judgement from people who hear a desperate person describe their life and assume that such unsightly emotions must be a sign of bad character. That’s a social problem, yes – ask me some time about how little help there is for kids with support needs and their families – but it’s a social problem Amelia only runs into because of her individual problem. She’s at home trying to solo-parent a little boy who is more than she can manage. If she can resolve a way to do it that just about works for both of them, she can tell society to get knotted. (Which, in the end, she very courteously does, and boy is that a cathartic moment.) Systemic issues make life a nightmare for Amelia, but if she can sort out the personal she can withstand the political. At least she has a nice house.

Tsidi is not in that situation. Her problems are both individual and systemic. Yes, she’s a single mother whose ex, if not a bad guy at heart, is certainly prone to grumble about helping her and liable to take the easy way out. And yes, she has a troubled relationship with her mother. The film resolves that latter relationship; I won’t spoil how, but in the end Mavis and Tsidi are in better order with each other. And when Tsidi isn’t rigid with stress, she and Luthando manage pretty well at staying friends post-separation. On a personal level you can see her getting what she wants.

But her problems are also societal. Why was Mavis a bad mother in the first place? Because apartheid made it hard for her to be much else. Why does Tsidi need to live with Mavis? Because she’s broke and there isn’t enough to go around. What would they do if they rejected Madam? They don’t own anything: they come from a culture where by design pretty much everybody had pretty much nothing for generations, and a few decades don’t resolve that. Obviously the film isn’t going to restructure the whole of South Africa at the end – but that’s the point about horror, and it feels like a point Good Madam just slightly missed.

Horror is the place where you come to terms with the impossible.

A monster is a metaphor. It must also be absolutely itself, otherwise it doesn’t work – but an imaginary creature really works when it speaks to real feelings.

And how you vanquish or succumb to that monster is the place where you reconcile, or don’t, with the thing that really scares you. You can’t change the world, but by condensing the world into some kind of supernatural form, you can wrestle it by proxy. In the realms of the symbolic, there is no scale too large to take on.

How that tussle comes out is up to you: you can be defeated because the evil’s unstoppable; you can destroy the monster to show the audience just what you think of the issue it draws out; you can come to some kind of reconciliation with it to show how uneasy compromises are the best we’re likely to get in this imperfect world.

You don’t need to spell any of this out: if the characters go through a climax where all the supernaturalness plays out in full force, and it ends it a way that feels right for that story, then we can feel a sense of catharsis about the theme without ever having to name it. Of course the Babadook ends up confined but not annihilated: trauma is something you manage, not something you can erase. Of course the Cenobites come back for Frank Cotton: kink and queerness aren’t going anywhere and it would be a disappointing world if they were.

Of course Invasion of the Body Snatchers ends without reassurance: you can’t reassure paranoia. Of course Kubrick’s Jack Torrance appears in the Overlook party photo: he’s always been on the side of evil. It’s not about whether the goodies survive or not, because it’s not about literal justice. It’s about doing narrative justice to the full horror of whatever scary thing you’re engaging with.

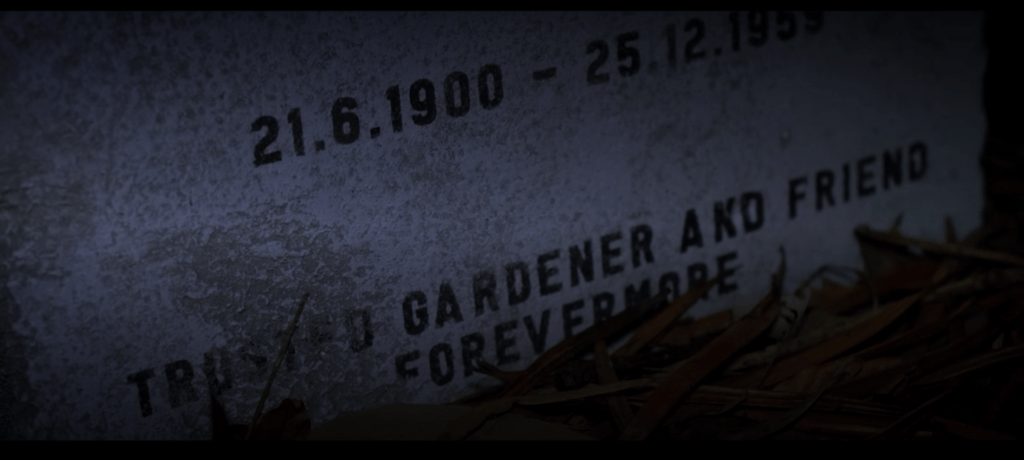

Good Madam is right on the spot when it comes to alienated families and unending labour. It has some good . . . things when it comes to horror; good moments and good props. Diane’s land has a private graveyard where all the former servants are buried under headstones that describe them by their jobs more than their selves, for instance, and that’s both horrifying and spooky. Diane has a sinister preoccupation with ancient Egyptian culture, and while that serves the plot in a slightly sketched-in way it also does feel like the folk magic of her white imperialist class: like everything else, Diane’s witchery originally belonged to another people.

But the horror side of the plot is a little underdeveloped. The domestic-drama reverberations are deafening, but the more traditionally horror aspects feel just a little tacked-on. The conclusion isn’t quite the banger the set-up deserved because the film, honestly, feels a little embarrassed to be including horror elements.

That’s really the nub of it: it doesn’t feel like this has to be a horror film.

By way of comparison, consider Guillermo del Toro’s anti-fascist films, The Devil’s Backbone and Pan’s Labyrinth. The ghosts and fairies that move through these stories aren’t just there for the scares: they’re how the real meaning of the story plays out. Fascism in The Devil’s Backbone uses the mentality of a juvenile bully to power itself forward; the violence of a juvenile bully haunts the story. Pan’s monsters are fascism incarnate – and they also remind us that part of the reason fascism is so powerful is precisely because it uses heroic narratives to twist your thinking. Little Ofelia lives in a magical world of fairy-tale quests, but her fascist stepfather Vidal lives in an imaginary world just as grandiose as any visions Ofelia sees – he just thinks he’s the hero when we can see he’s the monster.

Fascism ripped up Spain, and fascism has power because it knows that people think in myths. Del Toro points to the myths we should follow and warn us against the ones we should avoid, and reminds us that in the end we must always care more about people. If you took any of the supernatural out of these movies they wouldn’t be able to get their message all the way across, because the monsters and ghosts are the movie. They’re not the literal part of the story, but they speak of what hurts so much that it overspills a literal space. Pain and injustice and tyranny are real, but they feel hyper-real when they’re happening to you – and sometimes a hyper-real aspect is the only way to say that.

But if Good Madam had been a purely naturalistic drama about the fraught relationship between a mother and daughter in the aftermath of apartheid, and you’d stripped out all the supernatural aspects, it would have been an excellent film that made its points every bit as well. A troubled family guarding the home occupied by its near-comatose owner isn’t that far from Ian McEwan’s The Cement Garden, and that’s quite horrific enough without needing anything magical. The supernatural horror is about how the wealthy whites see nothing in their black employees but endless menial labour, and we know that, with our hearts as well as our brains, before a single supernatural thing happens.

This is, let’s be clear, because the naturalistic film-making is excellent – but it’s also all of what’s really good here. The horror aspects agree with the naturalistic side of the story, but they don’t elevate or deepen it. Like an echo, they repeat what was already said, but just a little quieter.

And that means that the societal side of the story – the theme rather than the plot – stays pretty much where it starts. Tsidi and Mavis are presented as better off at the end, but when you think through what the future holds it’s a bit of a fig-leaf, and the issue of victims outside their tight family circle isn’t ever really addressed beyond telling us that they exist. (A particularly disappointing omission for a film that so valued a more collaborative approach to scripting; I wish more of that community-mindedness made its way onto the screen.) Altogether the last act seems to have less to say than the first. If they’d just dug a little deeper into the mythology and metaphor, if the magic had been more than just a second to the motions that Tsidi is already tabling in dialogue, it feels like it could have done more.

Good Madam took on a heck of a problem to horrify us with, no question about it, and if it faltered in providing a fully satisfying solution – well, better ambitious and imperfect than safe and boring. But I do note that in the Slay Away With Us interview both Bass and Baartman state that they don’t intend to stick around in the horror genre: they’re moving on, Baartman to social noir and Bass to something ‘more frivolous’. The social side is their turf and they move brilliantly within it; the horror is something both of them say they aren’t big fans of. And because of that, it feels like they missed out on the opportunity to make full use of what horror does best: create a monster out of what is monstrous, so that the characters can enact a full-blown response.

Don’t get me wrong: watch Good Madam. The subtler stuff is worth the watch all by itself. I don’t know when I last saw a film with such a powerful atmosphere, or that managed to say so much about the ordinary corrosion of an unjust life. (Well, probably The Babadook, and that was a while ago.) I’d just consider it a foray into horror by a team that seem to have discovered they can play to their strengths better in other genres – but for the while they were here, we’ve been in luck to have them around. The final piece may be a bit less than the sum of its parts, but some of those parts are quietly spectacular.

In the Heart of Hidden Things (The Gyrford series) by Kit Whitfield

Jedediah’s father walked out of his life forty years ago. Now he’s back. He won’t apologise, he doesn’t explain – and, impossibly, he hasn’t aged a day.

If you asked the folks of Gyrford, they’d tell you Jedediah Smith looked up to his father. After all, Corbie Mackem was the Sarsen Shepherd: the man who saved the Smith clan from Ab, the terrifyingly well-meaning fey who blighted a whole generation with unwanted gifts.

Corbie was a good fairy-smith. And if he wasn’t a good father, well, that isn’t something Jedediah likes to talk about. Especially since no one knows where Corbie’s body lies: the day of his son’s wedding, forty-odd years ago, he set off to travel and was never seen again.

These days Jedediah is a respectable elder, more concerned with his wayward grandson John than with his long-buried past, and he has other problems on his mind. There’s the preparations for Saint Clement’s Day, and the odd fact that birds all over the county have taken to hiding themselves, and the misbehaviour of Left-Lop the pig – which has grown vegetation all over its back, escaped its farm and taken to making personal remarks at folks in alarmingly alliterative verse.

But then disaster strikes. Ab is back. And Corbie, thought long dead, returns to Gyrford – younger than his son . . .