How do you make a Hellraiser? The secret ingredient is love. No, really.

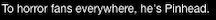

Content warning: we’re talking about the Hellraiser franchise here, so torture, gore, mutilation, medical abuse, suicide, sexual assault, addiction, suicide and a lot of blood, plus some discussion of homophobia and systemic oppression because, well, this is Hellraiser. I’ll leave at least a screen’s worth of scrolling before putting in any gory pictures, but there will be some.

We don’t want to let go of Hellraiser. The story first hit screens in 1987, a combination of astonishing monster design and genuinely transgressive implications; it shocked censors, delighted at least some critics, and got audiences well and truly, well . . . hooked.

The original story is a major classic. The franchise is a bit embarrassing. There are ten sequels – ten! – and most of them vary between ‘Kind of naff but at least they were trying’ to literal ‘ashcan copies’, goshawful nonsense produced on fifteen cents and a stick of gum for the sole purpose of keeping a legal hold on the franchise. Only the first sequel, released a year after Hellraiser in 1988, is taken very seriously; after that it’s an infamous case of an intellectual property in perpetual pratfall.

And yet we can’t stop trying. The ashcan copies struggled on till 2018, and then we got an actual reboot in 2022; HBO is supposedly still working on a television series. No matter how many times it hurts us, we keep opening that box.

Why? What are we really looking for? What could a filmmaker put in that box that wouldn’t leave us sighing when we wanted to scream?

It’s no mystery why sequels persist.

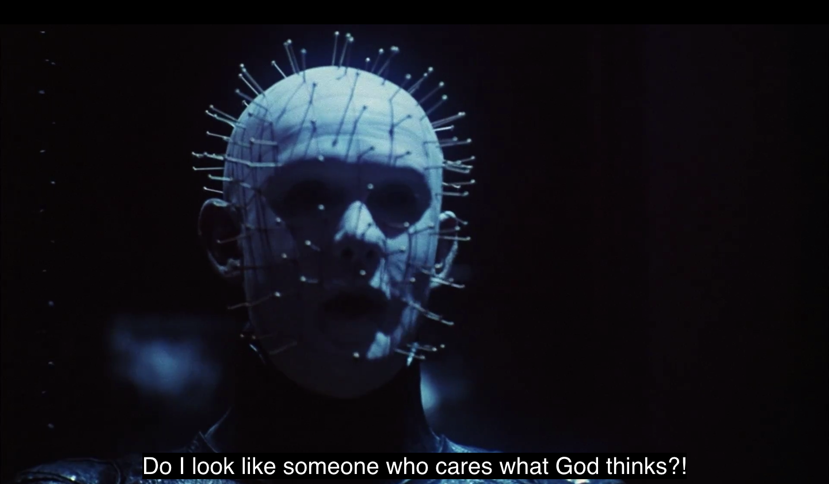

Hellraiser was ferocious and strange and incredibly memorable. It also had a fatal temptation: the visual iconography of it – the skin, we might say – was highly distinctive and easy to copy. You can get ‘Pinhead’ Halloween masks; that’s a brandable story right there.

But the spirit of it was a lot harder to capture. Very early on – I’m going to argue just before the final act of the second film – the people making these movies forgot what the story was about, what it was for.

The sequels may have some fun for you if you love special effects, but they don’t really feel like Hellraisers. They feel more like descendents of Nightmare on Elm Street: wisecracking monsters that invade from an unreal realm. At a certain point Freddy Krueger started wearing the skin ripped from the Cenobites, and it’s a pity.

No, the mystery is this: what went missing?

How do you follow up a story as mythic as Hellraiser? What made it work? What did the first film have, and to some extent the second, that made them feel special, and what did the bad sequels lack that made them feel – well, sometimes like fun enough popcorn flicks, but not like the real thing?

There are complex answers here, and it’ll take a while to lead you into the pleasures of that far realm, but stick with me. I’ve got an idea to put to you. A counter-intuitive one, but consider this: I think Hellraiser movies stop being Hellraisers when they get distracted by the sex and violence.

Where, amidst all the fucking and fetishes, is love?

I know, I know. What kind of chump expects love to be relevant in a story about leather-clad multi-pierced acolytes of pain stepping through the wall and flaying the malevolent sinners who summoned them to Earth? It seems like a question only someone whose pupils were cartoon hearts instead of circles could possibly ask.

Except it’s also the key to what went wrong with the series. So hold your patience, you can call me soppy at the end. But we’re going to get somewhere with this.

When you look at it closely, it becomes the question that turns the puzzle box inside out.

What are we going to cover?

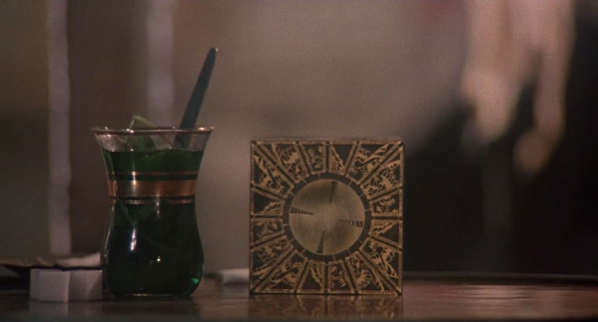

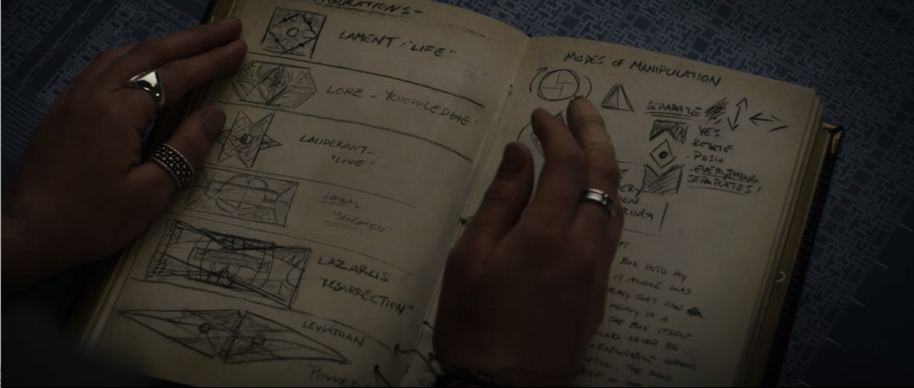

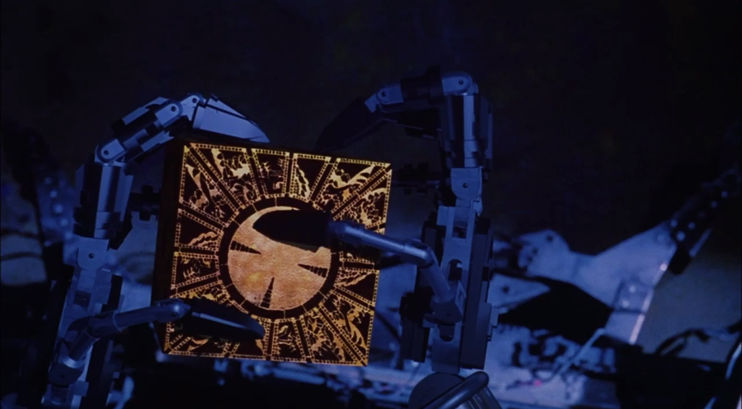

If you’re reading this at all I assume you’re familiar with the basic concept, but just in case here’s a quick refresher. There is a mystical puzzle box, traded among seekers and libertines, that is known to promise experiences far beyond anything this unsatisfying mortal coil can offer. It’s unnamed in the first film, and in the original novella The Hellbound Heart it’s simply called ‘Lemarchand’s box’, but it was later named the Lament Configuration.

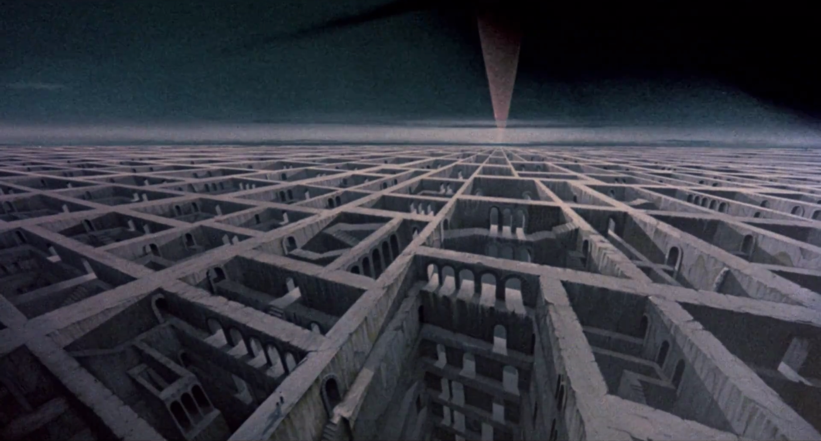

Open up the Lament Configuration, and creatures come and get you. They’re called the Cenobites – ‘explorers in the further regions of experience.’ A cenobite, in case you didn’t know, originally meant a member of a monastic community; it was the opposite of an anchorite, who pursued his faith in hermitage and isolation. So a cenobite is someone whose life revolves around devotions pursued alongside spiritual brethren. These particular Cenobites’ devotion is to pain.

But it’s a very specific kind of pain. And that’s what makes it a good or a bad story.

As well as the whopping eleven movies there are two books: The Hellbound Heart, which was the first part of this whole farrago and the basis for the original film, and Barker’s 2015 addition The Scarlet Gospels.

This is a ton of material, and if you’ll forgive me I’m going to confine myself a bit. Specifically I’m going to confine myself to The Hellbound Heart and the first four movies with a particular focus on the first two, and then loop round to the 2022 reboot.

Why? Theology.

One of the most agreed-on reasons why it all went to nonsense is that apparently nobody listened to the most important line of the first movie: ‘Demons to some, angels to others.’

The Cenobites of the original story inflict pain sadomasochistically: they do it to evoke a kind of agonised transcendence. However, past a certain point the motivation changes: they inflict pain demonically.

By the third movie they’re diegetically agents of Hell, doing it for a love of evil, and by the fourth there are other demons involved and the dialogue suggests that the Christian God is a factor too, albeit an apparently absent Father, and once the franchise had gone that way it was always going to go downhill – not because you can’t make a good Christian horror, you absolutely can, but because what was distinctive about the Cenobites was that they weren’t violators of human morality so much as acolytes of their own.

After the fourth movie the films started being released straight-to-video, and Barker’s Scarlet Gospels accepts the Christianisation the sequels inflicted, so while that’s entirely his prerogative it does make the second book a different beast from where we started. I’m going to stick to the novella and the movies released cinematically, because by that point the transfiguration is complete. Then I’ll skip a bunch of stuff to get to the 2022 film and see what’s recently cooking, because the question is, this:

Can the Cenobites ever go home?

For a long time the Cenobites have been seen as demons. They told us themselves that was only half of the picture.

The original Cenobites were dedicated to pain for its own sake – or rather, to limit-experiences. This is a concept from Continental philosophy, that great repository of mind-bending obsessions, and it’s a specific idea about what happens to you when you undergo something so extreme that it breaks down your dichotomies.

There’s an excellent essay on YouTube by the channel Morbid Zoo which I highly recommend; in it, academic Mariana Colin talks through the reasons why the Hellraiser franchise went wrong in its core tenet: treating torment and evil as synonymous. A limit-experience isn’t a punishment; it is, as Colin puts it:

Something in the potential of human experience that was unknowable by default, because to know it meant to reach a state from which it was impossible to return and explain what you saw . . . Events where the sensation you’re experiencing is so strong that it starts to warp your previously-held understanding of where the boundaries between diametrically opposed ideas like pleasure and pain, and life and death, really lie. This is what the Cenobites are doing.

So the Cenobites rock up, they sink hooks into you, they remove your skin and get to work with the mutilation – but not exactly out of sadism. Or at least not in the original story.

Instead it’s a kind of immaculate sadism: they inflict pain, but not out of hatred or a lust for power, or even really for their own pleasure as we would understand the word. They inflict pain purely because they’re interested in it. It’s evident from their bodies that they’ve undergone the same process and found meaning in it, or rather that sensation is the meaning.

Their cruelty is pristine; it is its own motivation.

This holds for the first film, and it’s what makes them so terrifying. Plead to be spared and you get the famous response, ‘No tears, please. It’s a waste of good suffering.’ It’s not that they don’t have mercy; it’s that they don’t understand the concept of mercy in the same way you do.

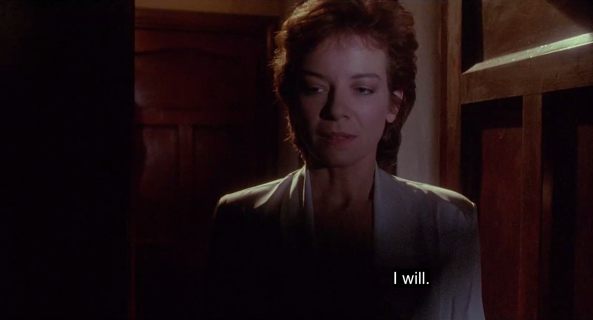

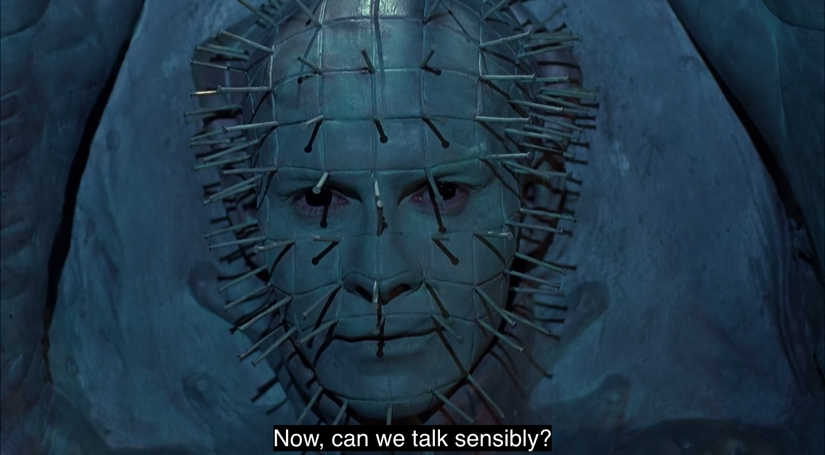

The original Cenobites are profoundly alien, not just in their appearance but in their language. The way they speak is formal, simple, flatly declarative, as if all their understanding is in their nerves and they don’t think in words at all. They’ll speak to you, but only enough to get across the plain information: ‘The box. You opened it. We came.’

Talking to the Cenobites in the first movie is like talking to things that speak English as a second language, and whose first language may not be verbal at all. Our heroine Kirsty (Ashley Laurence) tries to plead with them that she opened the box by mistake, but this isn’t a negotiation: ‘You solved the box. We came. Now you must come with us. Taste our pleasures.’

Dialogue can be underrated in its value to horror, especially with such spectacular special effects as we get in these films.

But the starkness, the calm incomprehension of how the Cenobites speak, is one of the most chilling things about them.

You’re made of saturated flesh and they can slice the blood right out of it, but there is no place in their minds for your consent. Beg them to stop and they just note your terror as another sensation for their reliquary. Communication is impossible with them – or at least, impossible on your terms. They communicate through sensation, and those are the terms that’ll rule the day.

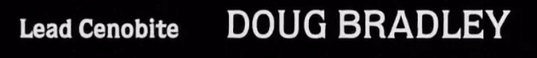

Once the script breaks that pattern their character changes completely – and it shows up a lot in the dialogue of later movies. They get talkier, and their talk gets different. Even how we talk about them changes. Did you know, for instance, how ‘Pinhead’ is credited in the original movie?

He doesn’t have a name. He just has a role. He’s the ‘Lead Cenobite’; that’s what he is. Names are for humans, and those are limits he exists beyond. It’s so important an aesthetic that you can describe the quality descent as the point where they stop being stories that feature a Lead Cenobite and start being stories about Pinhead. The Lead Cenobite and Pinhead are not the same being.

Now in justice, we should acknowledge that the original movie did plant the seeds of its own destruction. There’s a point where the Cenobites make threats – and that’s a problem, because pain as a threat is a human concept, not a limit-experience.

‘If you cheat us,’ they warn, ‘we’ll tear your soul apart.’

That’s a line that was used on posters. In the book it’s part of a bargain: give us what you promise and ‘Maybe we won’t tear your soul apart.’ I’m not sure which is better: the book version is more colloquial and hence less eerie, but also less of an attempt to be scary. Swings and spiky roundabouts.

But while ‘tear your soul apart’ is a banger of a phrase in whichever version you prefer, it does open the door to the Cenobites acting intimidating rather than fearsome – a subtle but important distinction.

On its own it wouldn’t be fatal, but unfortunately that line caught on. By the second movie there are more serious threats: ‘Your suffering will be legendary even in Hell.’ Again, a kickass line – but it’s trying to scare its listener, and trying is not a Cenobite trait: they don’t have to make an effort, they just do what they do and whether you’re scared or tempted is your own concern.

Once the dialogue starts going that way it’s inevitable that the scripts start accepting the human framing: that what they’re offering is straightforward Hell, not something more ambivalent. And so by the third movie, Hell and demons it is.

There is a point where they address the issue of Hell in the first film: Kirsty screams at them to ‘Go to hell!’ when she first sees them, and the female Cenobite (Grace Kirby) replies calmly, ‘We can’t. Not alone.’ But put a pin in that thought, I’m going to come back to it later.

Sharpen its tip. Drive it in deep. It’s oddly important.

Do you know the old saying, ‘Never argue with an idiot, they’ll drag you down to their level and beat you with experience’?

It’s been attributed to Mark Twain, though probably it wasn’t him. (A bit of quote-sourcing in case you’re interested: https://quoteinvestigator.com/2023/01/29/never-argue/.) But that’s a place where the Cenobites start to change. When we first see them they don’t argue.

Why would they? They’re not on our level. That’s what makes them so frightening. The dialogue starts to degrade in the later movies because they let themselves be drawn into discussion, like idiots.

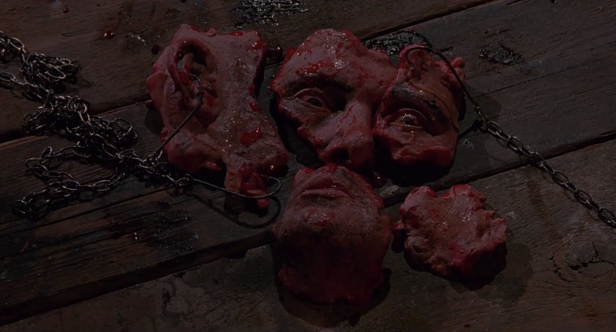

Not just conversation; by the third film, when the Cenobites escape and go on the gallivant in New York City, the lesser Cenobites even start making goofy puns; there’s one with a camera in his head who wisecracks about close-ups and says ‘That’s a wrap,’ after killing people, and the audience’s suffering is legendary even in cinemas.

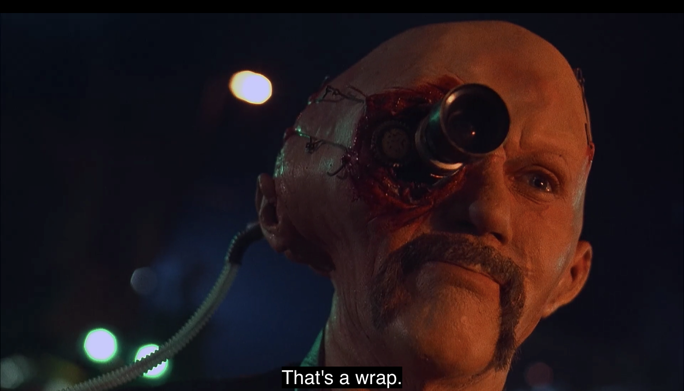

The stupidest remarks are kept for the underlings, but they seep upwards. ‘For God’s sake,’ pleads the hero of the fourth film, to which Pinhead snaps, ‘Do I look like someone who cares what God thinks?’ It was 1996, Buffy the Vampire Slayer was about to storm the airwaves the following year and Whedonish snark would permeate everything for a very long time, and further regions help us, even the stone-faced Pinhead is start to sass.

I’m very far from alone in complaining about the smart-alec dialogue, but I’m not just posting cringe. We’re here to talk about love in the Hellraiser movies, and that’s an important thing to start with. Love is a human emotion, and these cool-headed abominations are not human. They have no more compassion than the night sky, no more warmth than a waiting blade. So how could love play a part in their story?

The answer’s odder than you think.

To begin with let’s ask the simple question: is there love between humans in these stories?

Less than in most movies, by quite a wide margin.

We’ll start with the original. Dissatisfied hedonist Frank Cotton (Sean Chapman) gets his hands on the puzzle box and opens it. The Cenobites nab him and work him over. He escapes, or a scrap of his mutilated body does, and manages to haunt the room where he was first taken.

Since the house is now occupied by his brother, and his brother’s wife Julia (Clare Higgins) holds an obsessive passion for Frank since he seduced and then abandoned her in life, he is able to persuade her to help him. This means enticing men to the room so they can be murdered, allowing Frank to drain their life and rebuild himself.

This caper is thwarted eventually by the intervention of Kirsty. Now, who’s Kirsty? That’s a very interesting question that says a lot about love in this series.

In the film, Kirsty is Frank’s niece, the daughter of his brother Larry (Andrew Robinson). Larry is a harmless guy, a bit weak but nice enough. Kirsty’s a firecracker, a decent person but not one to take any shit, and she does not care for Julia because nobody likes a wicked stepmother. Kirsty gets hold of the box, opens it, is nearly dragged away by the Cenobites, but persuades them to release her if she can lead them to Frank instead. This she eventually does, not without a lot of blood and mess along the way.

This was a change from The Hellbound Heart – because in that, Kirsty is Julia’s romantic rival. She’s in love with Larry herself, although in the book he’s called Rory.

He’s essentially the same man, though his somewhat babyish qualities are seen through Julia’s eyes: she finds him ‘ridiculous’, his seduction talk ‘infantile obscenities’, his whole character ‘plainly a victim’; she resents her marriage for ‘the promise it had failed to fulfil.’ ‘She didn’t love him;’ Julia reflects, ‘no more than he, beneath his infatuation with her face, loved her.’

Kirsty, on the other hand, does love Rory. She’s a less attractive woman than Julia, shyer and plainer; ‘She had long ago decided that life was unfair.’ But she thinks of Rory as ‘sweet’, and ‘would not have turned down the chance of his smile for a hundred Julias.’

If this sounds a bit sparse as a depiction of love, it is. Kirsty is the hero, structurally at least, but we don’t hear very much about why she loves Rory except that she thinks he’s nice. Barker’s mind is on other things, and once she gets into conflict with the Cenobites the word ‘sanity’ is on Kirsty’s mind much more than ‘love’. The extremity they represent is a fascination to hedonists, but destructive craziness to Kirsty, and that’s what really drives her.

The movie changes all this. Kirsty’s motivation isn’t romantic or sexual but family love. But family antagonism even more.

Her love for her father plays a second place to her fear of the Cenobites and the sheer physical threat they represent. She has a boyfriend played by Robert Hines, but he’s so minor a part of the plot that viewers frequently forget he exists. Kirsty in the film is a fairytale heroine right down to the wicked stepmother and the evil uncle. Like Bluebeard’s wife, she looks behind the forbidden door, and from there on she fights monsters.

I’m not the best-placed person to do a queer reading, being cishet myself, but there is something delightfully genderless about this. It’s not only that the Pandora’s box she opens can be opened by anyone regardless of gender, though that’s fun too. In heroic tales, especially in the 80s, fighting because a man’s gotta do what a man’s gotta do was very much the province of, well, men.

Slashers had Final Girls, of course, but Kirsty isn’t in that kind of narrative. Instead she occupies a gender-fluid position: she peeps into the forbidden chamber like a girl, and then she fights monsters like a man. In that way she’s a match for the Cenobites, whose interest is entirely neutral on the subject of gender: any body can feel pain, so any body is a treasure house to explore.

But to step outside those confines, Kirsty can’t be motivated by romantic love. Barker was an openly gay man at a time only the brave were out, and The Hellbound Heart practises a kind of closeting. In the ostensible world, all romances are hetero and the sexes are complementary: ‘The seasons long for each other, like men and women,’ he writes, ‘in order that they may be cured of their excesses.’ Adam and Eve, order and moderation.

But if you don’t actually want to be cured of your excesses, there’s a gash in reality you can slip through. And once you’re there, gender means nothing at all.

Kirsty’s change from rival to daughter also fits with a more conservative note in horror movies, of course: for a woman to be motivated by romantic and sexual agency was not such an option back in the day. A daughter’s gender-bending ferocity is more excusable than a woman in love. And it also leaves us with the first big problem: the ending.

How do you return to sanity after a limit-experience?

The whole point of them is that you can’t. Which may be why the franchise went a little crazy.

Kirsty’s ending in the book is a good and apt conclusion. She’s left with Lemarchand’s box, ‘elected its keeper’ until another ‘voyager’ decides to take it on. She accepts it, facing another quest: ‘She would wait and watch, as she had always waited and watched,’ hoping that one day she’ll find another puzzle that opens the door to a more heavenly dimension that guards Rory’s beloved soul.

Nice, neat and thematically on-point. Pandora’s box was opened; now it’s closed with hope trapped inside. Believe me I mean it as more than faint praise when I say this ending feels correct. It strikes the note exactly. It just works.

So Kirsty keeps the box, knowing that another puzzle that would return her to Rory might never appear:

But if it failed to show itself she would not grieve too deeply, for fear that the mending of broken hearts be a puzzle neither wit nor time had the skill to solve.

See that there? That’s Barker being really smart. He’s addressing the issue of love – which is the missing piece of the puzzle.

Even die-hard fans of the movie will agree that its ending feels a little random. Kirsty runs away from increasingly animalistic monsters, escapes the collapsing house, and then is left outside where a skeletal dragon comes and snatches back the box. It’s . . . an ending, for sure. The special effects are great. It has smashing puppets. But without a romantic centrepoint to her story, we just have to enjoy it for what it is, which is splashier than the book and a lot less deft.

Let’s talk about sex, babies.

Hellraiser is saturated with sex – mostly kinky and figurative, but a lot of sex is. Lust is what drives Frank to open the box and start the story. ‘His real error had been the naïve belief that his definition of pleasure significantly overlapped with that of the Cenobites.’

Is there any love between Frank and Julia? On Frank’s part, definitely not, neither in book nor film. On the page he thinks of her purely in a connoisseur’s terms:

He remembered her as a trite, preening woman, whose upbringing had curbed her capacity for passion. He had untamed her, of course; once. He remembered the day, amongst the thousands of times he had performed that act, with some satisfaction . . . In other circumstances he might have snatched her from under her would-be husband’s nose, but fraternal politics counselled otherwise. In a week or two he would have tired of her, and been left not only with a woman whose body was already an eyesore to him, but a vengeful brother on his heels. It hadn’t been worth the hassle.

A delicacy on the menu, worth tasting once but too expensive to bother ordering again.

The implication of the film is a little different: cuckolding his brother seems to be the real appeal there. Frank makes a point of doing Julia on her wedding dress; that’s a fetish, and it’s a fetish for transgression.

The sex pretty much ruins Julia’s life in the film; from the very little we see of her before Frank, she was a lot more relaxed, a great deal sweeter, not consumed with the cravings Frank put inside her. This was the era of AIDS; it’s as if he infected her with his own unassuageable appetite.

Barker worked on the film as well, of course, but desire is less of a contaminant when he was the sole artist. In the book it’s the ‘beautiful desperation’ of Frank that attracts Julia in the first place, and the sex wasn’t even as good as he thinks it was: ‘Their coupling had had, in every regard but the matter of her acquiescence, all the aggression and the joylessness of rape. Memory sweetened events, of course.’

She was always hungry, always viewing him nearly as coldly as he viewed her. Which, since it’s nobody’s fault AIDS is a disease but it’s definitely the fault of homophobic governments that it killed so many of the young and marvellous, is a more compassionate way to look at it; contagion and corruption aren’t the same thing.

In the film it seems as if Julia’s in love. Violently, messily, sickly – but it’s for Frank Julia is killing. The book is icier: she reasons that if she can bring him victims to return him to life, ‘Would he not be grateful? Would he not be her pet, docile or brutal at her least whim?’ He wouldn’t, but that’s not the point: the film transforms Julia from an innate sensation-seeker to a woman doing it for her man.

Perhaps it was done for the sake of variety – two bleak libertines in a cast that small is rather a lot – or perhaps because the idea of a female libertine was too much in the 80s. But even in the film version, Julia’s ‘love’ is more a sexual passion than an emotional one. It couldn’t be anything more; beyond one ruinous fuck, they barely knew each other.

What is clear is that Frank doesn’t love Julia. Or his brother, or Kirsty, or anyone really.

And this gets to the nub of hedonism.

Must we always be in capital-L love to have sex? Of course not. But there’s another way of looking at love, which is about your relationship with humanity.

Are you a misanthrope or a philanthropist? Because even in the most casual of hook-ups, how you feel about people in general is going to make a difference. Sex is only ever sex, a transient experience whose glow quickly cools from your flesh – if it’s just sex. But for most of us, even casual types, it isn’t.

You might not want to marry your Friday-night booty call – but if you have a generally warm attitude to humanity and include them in it, then the memory won’t only be of how quickly the orgasm was over. It’ll be of how you had a good time with someone. Humans are social animals, and even brief encounters can keep us from drifting.

Frank, though, isn’t really with people. He’s purely a sensation-seeker. ‘The pleasures of Heaven or Hell,’ he explains. ‘I didn’t care which.’

And if you don’t care – well, of course nothing is ever going to be enough. You can have passionate sex on your future sister-in-law’s wedding dress, and five seconds later the discontent will return. Whatever you do to your body, if it doesn’t touch you emotionally then all you have is the escalation of chasing an ever-diminishing high.

So where does that leave Frank? Lying on a mattress with a stranger, having done no more than seal in flesh yet again what was already true in his soul, which is that nobody matters to him – and therefore nothing can.

How could it be enough? Sensations don’t cure heart-hunger.

There’s only so many times you can prove that you body-and-soul don’t care before your soul starts to notice that yeah, you don’t care. And that’s a cold comfort.

If you’re emotionally untouched, no amount of physical touching is going to do anything for you. Sensation passes.

You know what doesn’t pass, though? Damage.

A second in pain lasts longer than a second in bliss. A scar doesn’t go away. These are experiences that, quite literally, get through to you.

Let’s talk about romance novels.

Oi, get back here. I mean it, let’s talk about them.

Romance books are built on well-recognised structures; from Mills and Boon to Gwen Hayes’ guide Romancing the Beat, there is a recognised shape that love stories follow. One of the core components is what Hayes calls ‘retreating from love’, and what’s colloquially called the ‘third-act breakup.’

Essentially it goes like this. The lovers have had a moment of connection, a false high. Might be a kiss, might be sex, might be a tentative declaration, depending on your subgenre – but one or both begins to experience doubts. The connection is too frightening, too dangerous, too painful. So we have the retreat, followed by the ‘shields up’ stage in which they declare they’re never risking their heart like that again. They sink into a ‘dark night of the soul’, after which they come around and following various other beats are finally and permanently reunited with their beloved.

Humour me here.

Let’s tell a story. It doesn’t have to be about the 1980s kink scene; let’s go far afield and set it in the Regency period. Picture a snappy jacket and sleek breeches, maybe curly hair. You know the type.

There’s a man, full of passion but his heart untouched. He’s lived a wild life, but he’s afraid of real intimacy. He doesn’t want to let anyone in. Let’s call him a rake. A rakehell, you might say.

Then he meets someone. Someone who understands him. Someone who sees the real him, who’s a match for the real him. It’s fascinating – and it’s frightening. It’s vulnerable. When you’re used to the safety of ennui, real intimacy can feel like having your skin peeled off.

So he flees. This relationship is too much. It’s too dangerous. It threatens the security of his isolation.

That can’t be the end of the story, though. He has to accept in the end that the dangers of love are better than the misery of loneliness.

Quote the Song of Solomon, it’s the Regency era. It is the voice of my beloved that knocketh, saying, Open to me. I have put off my coat, how shall I put it on?

He’s been exposed and seen. How can he deny, in the end, that this place of painful, frightening, transcendent intimacy was his real home?

You see where I’m going with this, don’t you?

The skin of Hellraiser is horrific, but its bones are a romance. That’s the structure that holds it up.

Figuratively, of course. It’s all played out through sensation and special effects. But the real climax of both book and film is the moment when, in an ecstasy of ‘unrepentant lewdness,’ Frank is captured by the Cenobites and does not deny that it feels good.

‘I thought I’d gone to the limits,’ Frank tells Kirsty. ‘I hadn’t. The Cenobites gave me an experience beyond the limits.’

They gave it to him. Even in flight, he can only speak of it as a gift.

Kirsty has a story going on too, of course; hers is a fairytale quest. So does Julia – the tale of a murderer tempted, sinful, and then caught out at the end. There are three different plots going on, all of them classic tales, which makes a film with an hour-and-a-half run time feel near depthless.

And look, obviously being flayed upside-down isn’t most people’s idea of a romantic interlude. If you want fan fiction that ships Frank and the Cenobites then by all means write some and don’t send me any, but this essay ain’t that. What I am saying is that here in reality, the Cenobites aren’t real but symbolic. The position they occupy in the narrative is going to be very important on that level.

And structurally, Frank’s narrative is the third-act breakup and the dark night of the soul of a romance. That’s why it feels right at the end that he’s returned to the furthest regions. It isn’t a punishment; he’s happy about it. It’s because when the hooks fly, Frank is home.

It’s just that the love part happens offstage.

We only see glimpses of it, and what we see tells us two things: Frank was deeply ambivalent about it, and a normal person wouldn’t want it. But we also see that it answered what Frank was asking: it was, and more than, ‘enough’.

I know we talk about the Cenobites as an obvious image of kink, and of it taking place in the 1980s as a time when both medically and politically being a young gay man like Barker was dangerous. Is there an argument that what we see in Hellraiser is a story where love, metaphysically speaking, dares not speak its name?

Possibly. Queer theory isn’t something I’m an expert on and not my story to tell. What I can say is that the shape of the story is driven more by Frank’s actions than anybody else’s – and the pattern of what he does fits the pattern of a love story very well.

In the structural place of love, there’s a limit-experience. Or you could say that love itself happens beyond the limits.

Julia is married to Larry/Rory, but she doesn’t care about him. Frank fucks Julia, but he doesn’t care about her. In the real world, the ‘world of rain and failure,’ love that has any impact on the plot is unrequited, which is why it’s so hard to remember that Kirsty has a boyfriend: a functional relationship without pain just doesn’t do anything in a story like this.

What’s felt, what makes things happen, is a yearning for something out of reach – because when it is reached, it’ll rip the skin off your body and reveal you for the anguished, vulnerable pile of flesh you always were.

Intimacy is the starkest of all possible choices in the Hellraiser world. You either have nothing but your unmet wants, or else you submit yourself to being peeled and examined right down to the bone.

Remember the pin I asked you to put in earlier? Take it out and stick it back in your own skull. Kirsty screams at the Cenobites to go to Hell, and one of them responds: ‘We can’t. Not alone.’

The bad sequels took this as an acceptance of Kirsty’s terms: Kirsty is talking about the Christian hell where bad souls go, and the female Cenobite seems to be admitting that yes, that’s how it is, and she needs to take someone down there.

But drop a little blood in your eyes and it reads differently.

To me the line reads like a creature not interested in arguing over terms. Is it Hell she wants to take Kirsty? Heaven? What you call it is not the point. That’s just words, and words are not the language Cenobites speak.

No: the Cenobites are seeking an experience of transcendence – and they can’t go there alone any more than you could dom yourself. The far reaches of experience they study require a doer and a done-by. It works very well if you assume she’s interpreting Kirsty’s scream quite literally, and explaining the plain fact that ‘go to Hell’ is indeed an experience they seek, and it can’t be done without someone else’s flesh into which they can carve the map.

They’re the Cenobites. They’re a monastic community. What they do, by its very nature, is not a solitary business. They can’t go there alone any more than you can fall in love without someone to fall in love with.

So what happens when you’re left with only one half of the pair?

Because that’s the problem with franchise sequels for the most part, not just Hellraisers: they separate villain from story. You started with a monster intertwined with its victims; now you have an isolated monster looking for something to do. Whatever victims they pick up are always going to feel like . . . well look, this is a blunt review. They’re going to feel like a wank rather than a good fuck. They’re going to feel, like Frank Cotton feels in his predatory loneliness, like they’re ‘never enough.’

Here’s the question you should ask yourself to avoid that problem: whoever loves whoever else in this picture, whose is the love story with the Cenobites?

Because if you can find someone, and the story genuinely works like a twisted romance rather than a punishment eventually fitting a crime, that’s the difference between a Hellraiser and a bad imitation.

Does that love have to be romantic, though?

A limit-experience, if there is such a thing, is quasi-divine. As with any mystery, the whole point is that it’s impossible to come back from: you couldn’t possibly explain it to anyone who hasn’t been through it because it can’t be understood except by undergoing it.

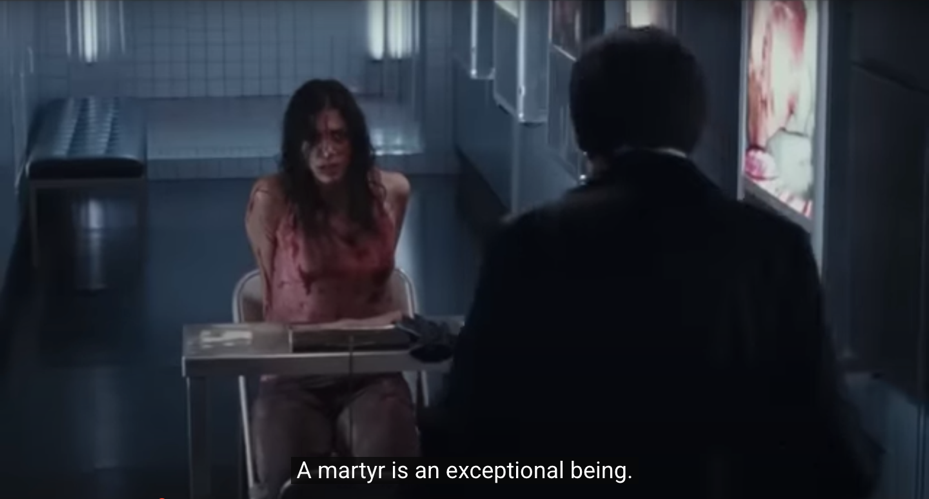

This is the same plot we see in Pascal Laugier’s 2008 Martyrs. Fittingly, the sidles up to its truth in terrified fascination, and it takes a number of mysteries and violent catastrophes before we find the underworld that really rests beneath this story.

In this case it’s a kind of spiritual laboratory: our heroine stumbles into a prison where wealthy seekers torture young women. Young women make the best spiritual subjects, you see: most are simply victims, but the seekers hope and they try and they try again and they do everything but pray to find a special case. Someone who’s a ‘martyr’: a witness who sees beyond this life, driven by pain to transcend her flesh and report on the divine.

Our heroine Anna (Morjana Alaoui) does achieve this transcendence. They take away her skin and she sees. But what she whispers of her revelation is something that the lead researcher can’t live with; it destroys her more thoroughly than she ever destroyed Anna. You can’t get the knowledge of a limit-experience without having a limit-experience; it didn’t arise from your flesh, and so your body rejects it.

Why does it happen to Anna but not to her predecessor victims? Well, Anna isn’t driven by suffering. She suffers; my goodness she suffers. But she came to that place not out of curiosity but because she loved Lucie, the girl who wanted to hunt the seekers down (Mylène Jampanoï). She stayed because she found another woman horribly hurt, and was too kind-hearted to flee without her. Everyone starts to hallucinate after enough torment, but Anna’s vision is of Lucie, whispering words of comfort and urging her gently to ‘let yourself go’.

To quote Howard David Ingham, who comes at it from a religious perspective: ‘Anna was always a saint . . . she is made of compassion.’ [Link: https://www.room207press.com/2018/11/cult-cinema-11-pain-is-point.html] Both emotionally and spiritually, Anna is deeply connected to humanity. She is the very opposite of a Hellbound heart: whoever she sees, she is in community with. She lives with and for people. She grew up in an orphanage and came out of it devoted to her fellow-orphan Lucie; she saw acts of terrible violence and responded by trying to heal all the pain she could.

The purpose of torture was to create a martyr by forcing someone to be spiritually moved by suffering. Being moved by suffering is exactly what Anna was used to. Give her misery and ask her to transfigure it, and she already knows how.

The heart is a muscle. Anna gave hers plenty of exercise.

So Anna is a martyr because even in the depths of torment, she’s led by love. It isn’t important whether her love is sexual, platonic or spiritual; she seems to be in love with Lucie and it’s possible they were a couple, but that’s not the point. Repressive Christianity can place sexual love and spiritual compassion in opposite corners, but Anna doesn’t: love is the root of everything she does – and that’s what transforms her anguish. If it wasn’t, she’d just be another victim and there wouldn’t be this story.

Of course, pairing love and faith isn’t necessarily comforting.

If anything, spiritual seekers of the past found Divine love a fearsome concept.

The Catholic poet Frank Thompson wrote a famous verse called ‘The Hound of Heaven’. It’s probably best known nowadays for being quoted in Daphne du Maurier’s Rebecca, where we see the first verse: ‘I fled Him, down the nights and down the days . . .’ It’s ferocious stuff. You can read the whole thing here – http://www.houndofheaven.com/poem – but the short summary would be to say it’s about an attempted flight from God that can only end by accepting the terror of Divine love.

Across the margent of the world I fled,

And troubled the gold gateways of the stars,

Smiting for shelter on their clangèd bars;

Fretted to dulcet jars

And silvern chatter the pale ports o’ the moon.

I said to Dawn: Be sudden—to Eve: Be soon;

With thy young skiey blossoms heap me over

From this tremendous Lover—

Float thy vague veil about me, lest He see!

The tale of faith as a pursuit, destructive and overpowering, by a force of Love so potent it’s terrifying until surrendered to, is very old. John Donne was at it in the sixteenth century; consider ‘Batter my heart, three-personed God’:

Except you enthrall me, never shall be free,

Nor ever chaste, except you ravish me.

Barker was playing with fire when he wrote a tale that hinted the notion of rapists as Gods, but he wasn’t the first. There’s a long tradition of legitimate spiritual poetry that pleads for God as rapist.

Which is why the second Hellraiser movie is so interesting.

Just as the first film laid a fairy-tale quest and a murderous descent alongside a daemonic love story, the second film lays two stories together. And one of them is religious.

I say ‘two stories’; I mean two good ones. There’s also the story about how the lead Cenobite used to be human, and the sequels take that down a Jekyll-and-Hyde path that leads to some really bad creative decisions. Kirsty’s back too with another heroic quest, tracking through the Underworld like Orpheus, and similar to the 1986 Aliens, the film excuses her taking such a typically masculine and active role by giving her an even more feminine counterpart: younger, blonder, and in the case of Hellraiser’s Imogen Boorman literally mute for most of the film. We don’t have to worry about these antics because they’re not the soul of the story.

No: we have two tales that make it distinctive.

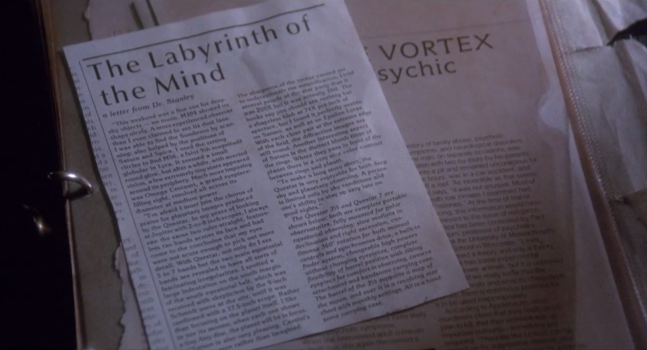

The first is a reprise of the Frank storyline, but done cleverly enough that it feels fresh. Kirsty begins in a psychiatric hospital, that traditional repository of horror-movie heroines with unpleasant truths to tell, and the great monster of the movie is its head psychiatrist, played by Kenneth Cranham.

Dr Channard isn’t like Frank on the surface. He wouldn’t rock a leather jacket. He’s middle-aged, respectable, authoritative, with all the power of class and education and gender and race and professional standing behind him.

He’s also a ruthless seeker. His interest in the Lament Configuration isn’t like Frank’s, at least on the surface; he isn’t looking to get laid-only-more-so. It’s a scholar’s interest, an intellectual hunger – and it’s every bit as rapacious. He spends the movie sacrificing patients to it, trying to get them to open it on his behalf so he can find out its secrets without having to pay its price.

It was too early for him to have seen Martyrs, but anyone with sense could have told him it was a bad idea. That’s not how you learn.

Julia resurrects, occupying the Frank position: flayed, fascinating, and prepared to bend someone to her will. Dr Channard is willing to do whatever she says if it gets him access to forbidden knowledge; we see a re-enactment of the driven murderer, Julia this time on the top.

Channard’s final attempt doesn’t go quite as expected. He chooses what seems like the perfect catspaw: Tiffany, Kirsty’s blonde, mute little friend who’s been silently solving puzzles in a hospital room. Of course she’ll open the Lament Configuration: puzzles are her jam.

Tiffany is coded autistic – a silent puzzle genius present and correct – but 1988, the year of filming, was not a good time to be autistic, and pop culture wasn’t going to help people understand you very much. It was unfortunately fond of the idea that autism was a kind of carapace with a not-autistic kid ‘in there’ somewhere, reachable if you just believed hard enough that you could.

That’s Tiffany: diegetically her muteness is caused by trauma rather than being non-verbal, her puzzles are thrown in because this was the cinema year that gave us Rain Man, but given enough support from Kirsty she suddenly snaps out of it and starts talking normally again.

If you want a good portrait of an autistic or traumatised person you need to look elsewhere, but functionally what this means is that within the story, Tiffany is a blank slate. At least until Kirsty does a number on her, all Tiffany is is nothing. Nothing to say. Nothing to want, except puzzles to solve for their own sake. She doesn’t even have a name; ‘Tiffany’ is just what the nurses call her because they have to call her something.

Such people don’t exist, but she is a narrative convenience.

Because when she solves the Lament Configuration, the Cenobites don’t want her.

‘No,’ says the lead Cenobite, rejecting her as if turning away a waiter bringing the wrong plate. ‘It is not hands that call us. It is desire.’

Because of course they wanted Channard. Tiffany wasn’t a real character to begin with.

We can acknowledge that this isn’t consistent; in the first film Kirsty opened the box and her pleas that she didn’t mean to got her nowhere. But it’s a great story moment, so let’s go with it.

Of course it was Channard they wanted. Curiosity consumes him; his mistake is to think it can be satisfied intellectually when the knowledge he seeks can only be gained by experience. Like Frank, he’s always been isolated, predatory, a lonely consumer, desperate for something that touches him but refusing to be touched. Like Frank, his heart craves, but is cold.

Hellbound.

That’s what it is to have a Hellbound heart in this series, and that’s the missing ingredient. It isn’t only about the Cenobites. They need a Hellbound partner.

And it’s not just about being a hedonist. The third movie has a pretty conventional bad guy played by Kevin Bernhardt who owns a club and has a lot of casual sex and more money than is good for him, but he doesn’t land as a Hellraiser villain because that’s all he is. Pinhead offers him ‘Flesh, power, dominion,’ and that’s not a Hellraiser motivation. A Hellbound heart doesn’t want power over others; it wants experiences in isolation.

Even more than the truly silly fact that he owns a statue full of Cenobite faces which can only drag in unwilling victims if they stand a foot away – I’m serious, if you’re two steps back the Cenobite clown car can’t reach you – this particular hedonist isn’t properly Hellbound because he isn’t a seeker. He’s just greedy and selfish, and we don’t need dimensional horror to deal with that.

No: being hellbound means craving experiences powerful enough to overwhelm your tormenting ennui, while remaining so saturated in contempt for others that you can’t engage with any of the human connection that makes experiences meaningful. It means wanting desperately to feel, without accepting that the price of feeling is vulnerability.

Frank and Channard want their hearts battered, but they weren’t prepared to let anyone in. They wanted to know what it felt like to be overwhelmed, but were so frozen in superiority that nobody mortal could make an impression. The end result is that they were already in a kind of Hell on earth: Frank endlessly chasing pleasures that couldn’t please, and Channard endlessly asking a question whose answer he couldn’t understand.

The heavenly hell of the Cenobites, however bloody, offers a kind of relief. For such men, it was better to undergo the unbearable than ask for the impossible.

The Cenobites are terrifying, but the thought that beauty and terror are inextricable goes back many centuries. The Gothic sublime is all about the idea that only things with an edge of the fearsome can be more than merely pretty. Go further back and read Aristotle with his discussions of tragedy. He had a word for how it feels when the fearsome and the beautiful are combined: catharsis.

A Hellbound heart is hungry, but so hardened off that the only way to reach you is to strip off every protective layer you have.

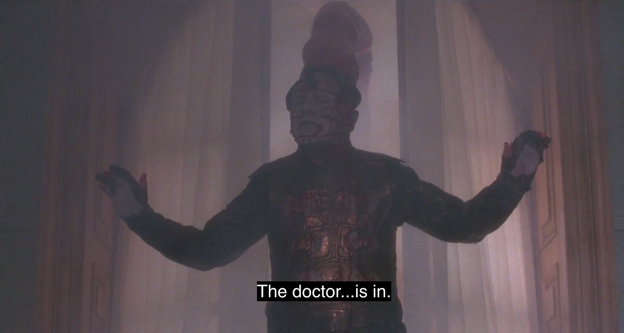

Which is why the Hellraiser franchise ends one hour and fourteen minutes into the second movie on a single line. Channard has been dragged away, given the Cenobite makeover, and emerged newly born.

‘And to think,’ he whispers in awe, ‘I hesitated.’

It’s a kind of orgasm. A kind of revelation. It’s exactly where his story was going.

And then he turns into the goofiest of movie monsters, capering around attacking his patients and cackling, ‘The doctor is in!’ like he’s in a panto, and from here it’s all going to be moustache-twirling and dad jokes and the franchise is finished.

‘He wanted pleasure, until we gave it to him,’ Cenobites say of Frank in The Hellbound Heart. ‘Then he squirmed.’ Well, we wanted a good movie, and this is the point where we start squirming in our seats.

But there remains the mysticism of Julia.

Julia comes back in the Frank role, yes. She tempts Channard into collusion. Like Frank she comes back skinless: literally as well as figuratively, her every protection has been peeled away.

But Julia, unlike Frank, got religion.

Deep into the movie, Julia leads Channard to the labyrinth at the centre of her far reach and shows him its mysteries. Channard exclaims, ‘Oh my God!’, but unlike in the fourth film, Julia has a much better comeback than, ‘Do I look like someone who cares what God thinks?’

No, she says. This is mine. The god that sent me back. The god I serve in this world and yours. The god of flesh, hunger and desire. My god, Leviathan, Lord of the Labyrinth. But this is what you wanted. This is what you wanted to see. This is what you wanted to know. And here it is. Leviathan! . . . Why do you think I was allowed to come back? It wanted souls.

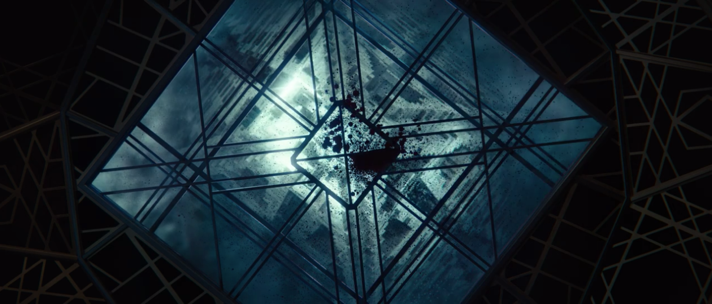

What is Leviathan? Have a limit-experience and you’ll understand. It’s a daunting structure, an elongated diamond that manages to be both phallic and vaginal while remaining more machine than flesh. It’s faceless, implacable, inexplicable except to its acolytes.

The movie was already slipping a bit by that point and Julia descends into straight villainy; it would have been fascinating to see the kinds of love that Leviathan offers. But this was too difficult and strange a concept for the sequels to grasp; they fell back on comfortable dichotomies, which is the worst choice possible for a story of transgression.

Leviathan rose for a moment, but it was difficult to build a story around. The writers squirmed. But the fact that what we see is inexplicable is part of the point: of course we don’t understand it. We haven’t been through the experience that would teach us to.

But Julia has. And it has something to do with love.

Julia was a lost soul once. But she wasn’t lost like Frank; she could feel for people. What she felt for Frank was fucked-up, miserable, destructive – but she was capable of being moved. She was willing to be vulnerable. What else are you if you fall for someone like Frank?

‘Love’, in the tender sense, is the wrong word for what she felt for him. Obsession, we could say. Or perhaps you should say she worshipped him. Adored him. She felt only he could save her from her dull existence.

Worship, adoration, salvation. We know these words.

Julia wanted something, and she knew that it would take more than mere sensation to get it. Frank was a first attempt, and she devoted herself to the glimpse he gave her.

Then something battered her heart.

How do you make a Hellraiser?

You can listen to ‘Hell’ in the language of the Cenobites. Not a romance, but a conversion narrative. Hell to some, Heaven to others, and the irreconcilability is the point.

You can tell it of Frank, a romance reaching its inevitable climax. You can tell it of Julia, experiencing revelations. You can tell it Channard, dragged out of his distant curiosity into real carnal knowledge.

But they can’t go to Hell alone – not because they refuse, or because it’s against the rules, but because it literally can’t be done. You can’t get anywhere meaningful alone. If the Hellbound heart had understood that sooner, they wouldn’t have been looking for meaning in a box.

The Cenobites are inside the box. As long as it’s closed there’s no plot. The story has to care passionately about who opens it and why, because ultimately what makes a Hellraiser crawl so deep under your skin is the fact that structurally, it’s a romance that lays waste to everything around it as bystanders get caught up in the damage.

A Hellraiser is what happens when you take two kinds psyche both incapable of love and make them dance a pas de deux. They whirl around each other, and the vortex they create drags down everyone in their vicinity.

Have we seen a Hellbound heart since the second film?

The bad sequels definitely don’t have one. I like the 2022 reboot, but for reasons I’ll go into in a moment, within this franchise I don’t think we quite have.

I’ll put forward an alternative candidate: Guillermo del Toro’s Pale Man from Pan’s Labyrinth.

Since I recommended Mariana Colin’s work earlier, before I go on I’ll also recommend her video in which she describes how apt an incarnation of Fascism it is: ‘A creature who can’t see anything unless it’s reaching out to grab it.’

I’d like to elaborate on something I see in the Pale Man (Doug Jones). Obviously the beast is a representation of Captain Vidal (Sergi López), the Fascist stepfather of our little heroine Ofelia (Ivana Baquero), who tortures and plunders his way through the countryside around his mansion. I think it’s very significant how thin the Pale Man is.

Its table groans with luscious food. The figure itself is emaciated, its flesh hanging in folds as if it once was fat but has gone for a long time without a bite. It doesn’t eat. It sleeps. Even with this feast before it, it’s skin and bone.

Why?

We see the answer once it wakes. The Pale Man doesn’t want to eat. It wants to hunt. If it doesn’t get to kill the thing it eats, it doesn’t seem to see it as food at all. To the Pale Man, even at the cost of its ruined body, nourishment isn’t a real enough idea to act upon.

No: the purpose is consumption. It only lives by destroying other lives.

If this were an animal, we could say that its appetite is only triggered by its predation instinct, a snake that won’t eat the thawed mouse unless you wiggle it around. But look at it. It’s not an animal. It’s capable of knowing better. It just . . . won’t.

Vidal is only mortal. But he is, body and soul, a vain man: his dream is to be the Fascist superman, the heroic patriarch beyond mere common humanity. He tends his looks and his smart uniform; he’s devoted to the romantic myth of himself as a grand link in a chain of honourable fathers and sons. We see a man far lesser than those around him – but he sees himself as something much greater.

Other people, to Vidal, are simply flesh stages upon which to stamp out his dance of self-admiration. His wife is nothing more to him than a seed-bed into which he can plant and then tear out a new image of himself, even it kills her. The people who live in the surrounding countryside are victims, flesh and blood he can rip apart to enact and re-enact his endless drama of dominance so he can admire himself as he kills them.

The people he hurts are good and loving. If Vidal wanted to be a man among men in the healthy sense of the words – if he wanted feast together rather than feed on blood – there is enough and more to nourish him in his surroundings.

But he doesn’t want it. He doesn’t know how to value anything that isn’t himself, or even to see it as anything other than a prop in the drama he performs with himself as sole audience. Like Frank in The Hellbound Heart, all he wants is to ‘bend the world to suit the shape of his dreams.’ The only way he knows to enjoy another person is to consume them: their resources, their freedom, their fertility, their dignity, their life.

He doesn’t want to eat. He wants to hunt. He doesn’t know how to feed on something he isn’t killing.

It’s as if we see a Cenobite turned inside out: the grotesque monster is Hellbound hunger, wanting to feed but not knowing how to be nourished, while the normal-looking man is a monster that takes pleasure in torture. Vidal looks more like Frank but acts more like a Cenobite, while the Pale Man looks more like a Cenobite but is, in essence, a Hellbound heart removed from its body and set up for us to see in all its abjection. Both, though, are monstrous perversions of the most primal of human acts, reducing eating and communication to acts of pure dominance. Surrounded by chances to do better, they feed and express nothing but ego.

That’s how serious it is to have a properly Hellbound antagonist set up against the Cenobites. It can’t just be greedy. It needs to sit at a table full of food – and it needs to be starving.

There are two places you can fail to make a Hellraiser. The first is the Cenobites: turn them into straight-up demons and your movie is going to be bad. But the second is to underrate the importance of the Hellbound heart.

Which is why I’d argue that the 2022 reboot is a good film – but it isn’t exactly a Hellraiser.

What’s the story? In broad strokes: Riley (Odessa A’zion) is a nice young woman a few months into sobriety. She lives with her nice brother Matt (Brandon Flynn), his nice boyfriend Colin (Adam Faison), and their nice roommate Nora (Aoife Hinds). She’s broke and not very far into rebuilding her life after an addiction to alcohol and pills, but her living situation is something we don’t see in most of the other movies: it’s genuinely warm and touching.

Where’s the love? Well, it’s right there. The characters are feasting on it, and they’re feasting together.

Riley and Matt have conflicts – he’s worried about her staying sober and she’s prickly about that – but they’re clearly devoted to each other. Glory be, the 80s have passed and we now have gay characters in movies being normal decent people; Colin is a sweet guy and he and Matt have a lovely relationship where they lie in bed quizzing each other on Romantic poetry, and it genuinely rejoices my heart to see that existing in a film without comment.

Nora might be a bit of a third wheel – she’s not dating or related to anyone in this apartment – but she’s obviously part of the found family and everyone shows everyone else genuine affection. I did not want to see these characters get hurt.

Trouble: Riley recently started dating Trevor (Drew Starkey), which since they met in a 12-step program she shouldn’t be doing. But again, we’re in a much warmer place than the 80s; we first meet them having sex, and again it’s presented very normally: she makes happy noises and also asks him to change his rhythm, change position, this and that, and he’s happy to do it and they’re both having a great time. An amazing thing to see in a Hellraiser film: fully consensual sex.

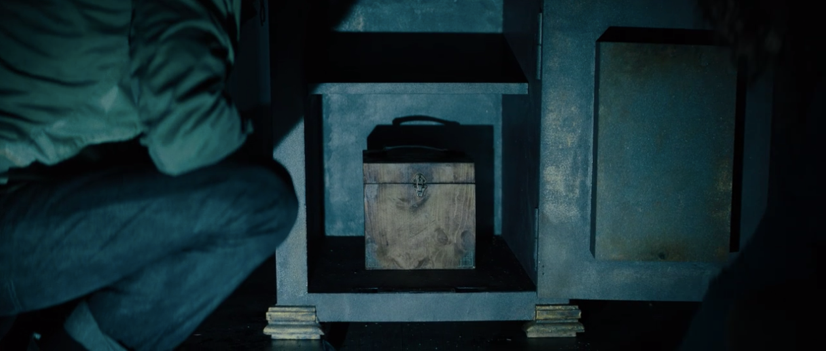

But Trevor knows Riley’s broke and suggests a bit of a crime caper: he used to deliver works of art to a warehouse he knows is now unguarded, so how about they break in, half-inch the valuables and sell them?

Guess what the only thing in the warehouse was?

I can’t describe the differences without spoilers, so if you want to duck out now, consider it a conditional recommendation. The originals had a dirty grandeur to them; you come away feeling implicated and contaminated, like you’ve done something wrong by watching them. (I say this in praise.)

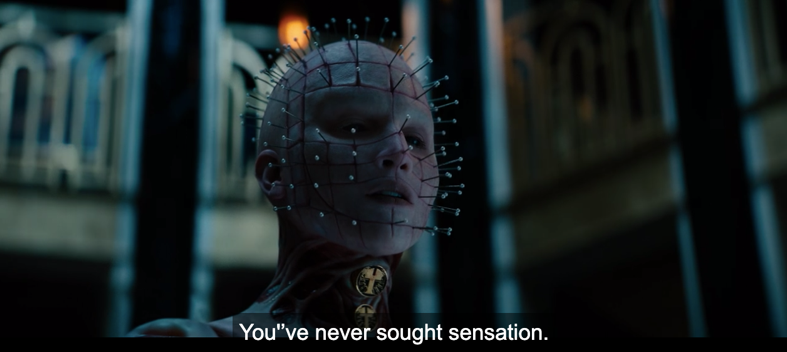

The reboot is attractive and warm and engaging and a lot of nice things, which is good but not the same. The art design is fantastic, the new Cenobites are an absolute chef’s kiss, and there really is a lot of great stuff in there. They call the Lead Cenobite ‘the Priest’ rather than ‘Pinhead’, so they were clearly paying attention and eager to avoid the mistakes of the bad sequels.

If you can accept it as something new you’ll probably like it; it’s undoubtedly influenced by and respectful of its predecessors. But if you’re looking for it to capture their full spirit you may come out feeling a bit dissatisfied.

The issue is that they’ve changed the puzzle.

In the originals the rule was brutally simple: you open the box, they come, they take you away and that’s that. They could be a little flexible for the sake of story, but it was played quite carefully: Kirsty only escapes because she trades off Frank and the Cenobites seem more concerned with losing an existing playmate than gaining a new one; Dr Channard was so obviously Hellbound that not taking him would have seemed ridiculous.

In this new version, there’s a grace period. A claw shoots out of the box and draws blood, and then you’re marked. At some point a little later, Cenobites will come and get you. Exactly why there’s a delay is unclear; the film does very well building up suspense, but more in the creepy style than the dizzying lurches of the original, so enjoy it for what it is.

Once the box cuts you, you’re tagged as a victim – and how you got cut means nothing. Matt gets cut and stolen away, but he didn’t even open the box; Riley did, and then he picked it up. Nora gets stabbed in the back by an unseen assailant. At one point an actual Cenobite gets cut, and it’s accepted as an alternative with no questions asked.

So there must be a Hellbound heart setting all this up, right? Yes, there is. We can tell who it’s going to be from the first scene in the film, where we hear a wealthy man (Goran Visnjic) described as someone who ‘never does anything he can get else someone to do for him.’ Even if his name wasn’t Roland Voight, a baddie handle if ever there was one, we recognise who he should be. The scriptwriters were paying attention to the better movies. But there are a couple of problems.

The first is that Voight seems to be DOA. Once the plot really gets underway everyone thinks he’s dead, and he only pops up again in the last act. Where in the originals the far reaches of experience happened offstage, here the motivations of the seeker happen offstage: we see so little of him that we can only find a generic hedonist. He didn’t get enough time to develop into anything else.

So when he says, ‘I had experienced everything afforded to men and still I wanted more . . . But the Cenobites – their tastes were not what I imagined,’ I’m glad they bothered to read The Hellbound Heart because that’s obviously a reference to Frank’s thought that he was wrong to assume ‘his definition of pleasure significantly overlapped with that of the Cenobites.’

But it falls just a little flatter. It sounds less like a troubling redrawing of your mental boundaries and more like simple buyer’s remorse. When we don’t actually see Voight’s yearnings in any kind of detail, he seems less like someone seeking esoteric extremes and more like a fairly ordinary rich brat kissing up to the cosmos’s most exclusive fraternity purely because he knows they’re exclusive. ‘More’ is the sum total of his motivations, and the audience is Frank Cotton over here: that’s not enough.

The second problem is, once again, about love. But this time it’s community love.

The first film showed an outwardly respectable nuclear family disintegrating under the pressures of inner transgression. The second showed isolated people lost in institutions. Love, except between the seeker and the sought, was really not much of a motive.

But in this version, our little band of victim-heroes are very loving people. More than once Riley states that she knows she could save herself by sacrificing a friend, but she refuses to do that. Trying to find ways to meet the Cenobites’ demands without losing any more loved ones is her whole motivation, and her friends stick by her with just as much courage and loyalty.

So what are the Cenobites here?

They look magnificent. Both in special effects and performances, these are some really good Cenobites.

The dialogue is good too; clearly the writers were listening closely to the original scripts, and there’s no sass. They’re a bit talky – they’ll philosophise and explain themselves rather than strike you with bald statements and carry on – but the explanations themselves are poetic and apt. They capture poor Nora, and we have another chance to see how these Cenobites react to prayers for mercy:

Cenobite: What do you pray for?

Nora: Salvation.

Cenobite: What would it feel like? A joyful note? Without change? Without end? Heaven? There’s no music in that. Oh, but this! There is so much more the body can be made to feel. And you’ll feel it all before we’re through.

You can see some of what’s going on in that speech. They’ve got the philosophical stance of the Cenobites: they aren’t punishing, they’re pursuing their own notions of beauty. But they’re also kind of chatty, which is the beginning of the real issue with this movie.

Like I say, there’s a lot that’s great about it. If it was an original story about a group of demons or fairies or aliens who like to pull this kind of shenanigan I’d have very little to criticise.

But despite the initial promise, it turns out that the Cenobites have no Hellbound heart to dance with.

Their victims are chosen entirely at random – and from a pool of people with intense emotional relationships to each other instead of the Cenobites. The purpose of the puzzle box isn’t to summon them to you; it’s to mark you for sacrifice.

The original Cenobites offered something very simple. You open the box, they come, they show you such sights.

These Cenobites have something more complicated going on, and a lot less primal. They’re engaged in a deal: one boon from the God Leviathan, which you can choose from a list of six options, in exchange for half a dozen victims. It’s Channard’s dream, really: you actually can give them other victims while you stand back and watch.

It’s just that the boons are monkey’s-paw gifts: you technically get what you asked for, but in the worst possible way. Voight asked for sensation, so they jammed a torture machine into his nerves. He’s now making a bunch more sacrifices so he can ask them to take it out.

Which they do. But the speech with which they twist his request is the place where I started to feel disappointed in an otherwise good film.

‘Perhaps we were wrong about you,’ the Priest said. ‘You’ve never sought sensation. Your whole life, every conquest, all your pleasures lie in power . . . For your efforts, we offer the Leviathan Configuration . . . Our power lies in dominance. In the sovereignty of anguish. And now it will be yours to wield.’

So they Cenobite him up, turning him into one of them. Which apparently they no longer do to everyone; most of their victims they just hack to bits.

Do you hear that? Our power lies in dominance.

The Priest just told us that the Cenobites themselves aren’t about sensation.

If they’re not about sensation, they’re not Cenobites. And they’re even less Cenobites when they have multiple gifts they’re willing to swap around. This feels less like a primordial terror than like the customer service department of a shop with a complicated returns policy: they’ll only exchange for store credit but they’re interested in making sure your suffering is custom-made.

But where these Cenobites end the movie like tailors, snipping and trimming to make sure your suffering perfectly suits you, the original Cenobites were procrustean, slicing off pieces of you to fit the mold of suffering they have decided to pour you into. It’s so hard for sequels to keep it simple, but that’s the core of it.

The simplicity of what the Cenobites offer set against the nuances of human feeling acts as the pins and the flesh, the hard and the soft placed in transformative union.

And it’s difficult to make a complete plot out of that, especially one that feels satisfying. Part of the lasting power of the original is that it leaves you, Lovecraft-like, in a cosmos less safe than you once were; you come out of the story changed, but you don’t come out of it satisfied. Your sense of what satisfaction feels like has been mutilated to the point you don’t want any; that’s what the movie is for.

So yeah, Riley runs around making sure the right people get sacrificed and she saves the last person left she loves, which is Colin; she gets offered a boon and turns it down, and is told that she’s therefore chosen a lifetime of mourning, which, fan shout-out, means she’s chosen the Lament Configuration.

It’s clever, but it’s also a bit of a simple moral that doesn’t at all suit a story about ravening ambivalence. The power of the ambivalence has gone away somewhere.

I think what’s happened is that times have changed and the movie hasn’t quite caught up.

Back in the day, the box mattered because you were a danger to yourself. There was something in you that chased things beyond what mortal flesh can sustain. Or at least, what it could sustain in a respectable world. In the 1980s, that excluded quite a lot.

I wish we lived in a world where I could say that sexuality and gender are no longer reasons for persecution. I really do. But we do at least live in a world where the idea that people on the margins aren’t just punk monsters has some foothold in the mainstream – and that’s where the movie stands.

‘Drug addict’, in the 80s, was a phrase almost as scary as ‘Cenobite’; the stigma was enormous and pop culture often treated such people as monsters. In 2022, Riley is a recovering drug addict and she’s our heroine, and she’s dating another recovering drug addict to boot. Matt, meanwhile, is gay. So is Colin, and both he and Nora are people of colour. This is a tight group not just because they’re nice people, though they are, but because nice people who aren’t at the top of the tree have to band together if they want to survive at all. Even if it can’t keep you safe, solidarity is how you stay sane.

Which means that the real threat of the Cenobites in the film isn’t what they do physically. It isn’t even what they do philosophically. It’s that they threaten the solidarity of the group.

Way back when, the Cenobites were the incarnation of transgression. They were, in every sense, out there. But now the people they’re chasing are people who for one reason or another would be seen by the powerful as transgressors themselves, even though they’re living lives of innocence and moderation.

The most coherent symbolic meaning of these Cenobites isn’t as a temptation to leave the normal world. They’re more like they embody the normal world.

Not visually, of course. Quite the opposite: their design specifically reaches out to the margins of society. The Priest is played by Jamie Clayton, who’s a trans woman; before they cast Clayton they auditioned trans man and drag performer Gottmik. The idea was always to play up the ‘sexless things’ that Barker described and have someone who didn’t fit neatly into traditional binaries.

More than that – and I don’t know if they entirely thought this part through – one of the Cenobites is credited as ‘the Asphyx’ (Zachary Hing), and its body is built around the idea of suffocation. Skin covers its face, and it wheezes through its opened-out back with an agonised rasp that sounds like the last stages of lung cancer of emphysema.

Which is an ironic nod to the fact that the mini-villain they’re coming to cash in (Hiam Abbass) is dying of lung cancer or emphysema; ‘My lungs are rotting out,’ she explains.

And that’s a little troubling thematically.

If they were going for the Cenobites as demons it would be a case of the punishment fitting the crime, but that doesn’t hold up because the woman’s crimes have nothing to do with her lungs. She’s just dying of something because everybody does.

Or is it a mockery of the decay of her body? Perhaps, but again, body-shaming doesn’t seem like a Cenobite trait. They like all bodies equally, as far as we can tell, just as long as they’re capable of hurting.

What feels like the most natural explanation would be that it’s a kind of echo of her: that they knew her lungs were damaged and thought it might be interesting to try that for themselves, or else like the greatest pain she currently knows conjured up a Cenobite in its own image. Just as Jamie Clayton’s Cenobite invokes the act of transcending gender, the Asphyx invokes illness.

Neither of which is a trait valued by the powerful.

Put it this way: when it comes to social policy, queer people and sick or disabled people tend to be on the same side. The same people hate us.

In design, the Cenobites look like carnal exaggerations of the kinds of people that respectable society renders vulnerable. That’s how they functioned in the original movie.

But in practice, what they do in this movie is chase after socially vulnerable people because a billionaire offered them up as sacrifices.

The drama they create is the drama of persecution.

You have a group of people you love, and all of you could be got for something if the eye of dominion fell upon you. So you protect each other. You keep each other under the radar. You guard each others’ secrets. You hope the greater powers’ gaze doesn’t see you.

And if it does, you hope you’re a good enough person not to throw your friends into its maw so it’ll take them and leave you. You hope you’re strong enough not to sell your loved ones out.

These Cenobites look like outsiders, but they function like mainstream powers.

They’re stronger than you, and you as a human being are so unimportant to them that it doesn’t actually matter if they get you or someone else. You can turn in your friends and they might as well pass you by. One will do as well as another. They’ve got a quota to fill.

Now, I want to be clear that they function well as embodiments of power.

That’s a fine movie to make, and Hellraiser 2022 actually does an unusually good job of it. The characters are all endearing and their casual but heart-deep loyalty is well drawn. Matt and Riley have a fight about her drinking; she yells at him to get out of her room; he steps out and continues to fight with her from the safe side of her boundary.

That’s one of the best little moments of loving brotherhood I’ve seen. There’s a moment where the whole gang overhears Riley and Trevor having sex because that’s what happens when you can only afford a small place together, and they just laugh it off; again, it feels natural and sweet. Riley storms out after Matt tells her to leave for drinking and Colin pleads with her to stick around because Matt will realise he didn’t mean it tomorrow. These are all great depictions of what it’s like inside a group of outsiders.

Likewise, the drama of whether you’ll sacrifice a beloved member of your survival gang to protect yourself is a really good thing to turn a plot around. It gives you stakes; it makes you care; you want to see solidarity win out so you can punch the air and then go hug your friends. This is all great stuff.

It’s just that if the Cenobites had been a totally different kind of monster, it would have done all that just as well. The Cenobites look great and give excellent performances, but seeing these incarnations of sexual outsiderdom chasing down actual diegetically gay people is . . . a bit odd.

It once again comes down to love. There’s plenty of love in this Hellraiser, and it has nothing to do with the Cenobites.

It’s a reason to resist them, but it’s not as if the Cenobites don’t give you plenty of reasons even if you’re a total misanthrope. All the love in this film is mortal. The character best placed to be Hellbound is Voight, and . . . well, he isn’t in a romantic relationship with them. It’s a business relationship.

A bad business, but not quite Hellraiser. The Cenobites say themselves he’s interested in power rather than experience. ‘Some rich asshole,’ in Trevor’s words, being dedicated to gaining more power whatever the cost to others? There’s nothing more ordinary in this world.

I think this film’s heart is too heaven-bound.

The story is of a diverse group of friends trying to get by in a difficult world. Even the Cenobites don’t act under the drive of their own perversity so much as they do at the behest of rich assholes. Its sympathies are with the outsiders – but to such an extent that I think it has difficulty identifying genuine darkness.

Hellraisers depend on some kind of repression – the Cenobites are as extreme as they are because that’s how large temptations loom when you’re afraid of them – and the original two were deft at identifying that repression in general may be bad, but there are at least some impulses that one ought not to indulge.

Not sexuality; Barker was the last writer to be prudish about that. No, what Barker’s story recognised is that sexuality can be both a cover and an outlet for the real sins.

Vanity. Selfishness. Callousness. The temptation to exploit. Its real monsters were human, and what was wrong with them wasn’t their odd interests but their willingness to sacrifice others.

But this film is about people who won’t sacrifice others. The one person who’s willing to is Roland Voight, who hides for much of the story.

It feels as if the film is hesitant to judge. The only character it does judge is Voight, who it has to under-characterise, keep off-screen as much as possible – and then when he turns up he’s in so much pain that it’s hard not to squirm on his behalf at least a little.

And the other thing is that they had the theme of addiction right in their hands and they didn’t do anything with it. Great big spoilers coming up in this section . . .

Riley, we know, is trying to stay off drink and pills. There’s a moment of relapse where we see her pill box, and it is, like the Lament Configuration, an object of beauty. I was optimistic that we might be seeing some thematic play there: you surely don’t introduce the idea into a film without meaning to do something with it, especially when the original book says of Frank’s interest in the box addictive: ‘This new addiction quickly cured him of dope and drink.’

But somehow that’s what the film does. The only effect Riley’s addiction has on the plot is that she first opens the Lament Configuration after she’s relapsed and taken some pills following a quarrel with her brother Matt, and all that means is that when the Cenobites come and grab Matt she’s too high to have a clear idea of what happened.

That’s it.

We don’t see her struggle to stay sober after that no matter what nightmares she goes through. We don’t see it reflected in her character or affect her feelings except for a generally low self-esteem at the start. All it does is make her overlook the Cenobites the first time around so that the film can build up suspense for a while longer. A non-addict who happened to be drunk or high could have done the same thing; a bump on the head or distraction by a third party would have done as much with Riley.

Trevor, meanwhile, is someone she met at Twelve Step and sensible Matt thinks that’s a bad place to pick up guys, but it’s quite surprising how his issues with drugs don’t affect the plot either. This is the main spoiler: Trevor turns out to be a bad guy. He’s been hired by Roland Voight to bring him sacrificial lambs. But why did he say yes?

Really Voight’s explanation is the only one we get: ‘This is the best deal of his miserable life.’ And yeah, none of these twenty-somethings have very much money and Roland has lots.

But does Trevor have debts to dealers he has to pay off if he doesn’t want his legs broken? Is he paying back for stealing stuff to feed his habit? Does he need to keep his apartment if he doesn’t want to go back to prison? No. Is Trevor trying to be a good person and Voight is his last bad link, something that he eventually – let’s use the word ‘relapses’ into? No again. Neither narratively nor thematically does Trevor’s history with substances really mean anything. He could have just been a corrupt hireling and the plot could have gone right ahead.