Mackenzie Crook: Weaving Gentle Spells as Folk Horror’s Modern Gatekeeper for Children

In the landscape of British television, a quiet but profound magic is at work. An unusual gateway is opening for a new generation, not through terrifying films or eerie novels, but through the gentle, whimsical, and deeply heartfelt stories created by Mackenzie Crook. Through his trilogy of works, Worzel Gummidge, Detectorists, and the upcoming Small Prophets, Crook is reframing the core elements of British folk horror into accessible, child-friendly adventures. He is becoming the foremost modern guide, leading children into the uncanny valleys of folklore, landscape, and supernatural yearning, all without the need for outright fear.

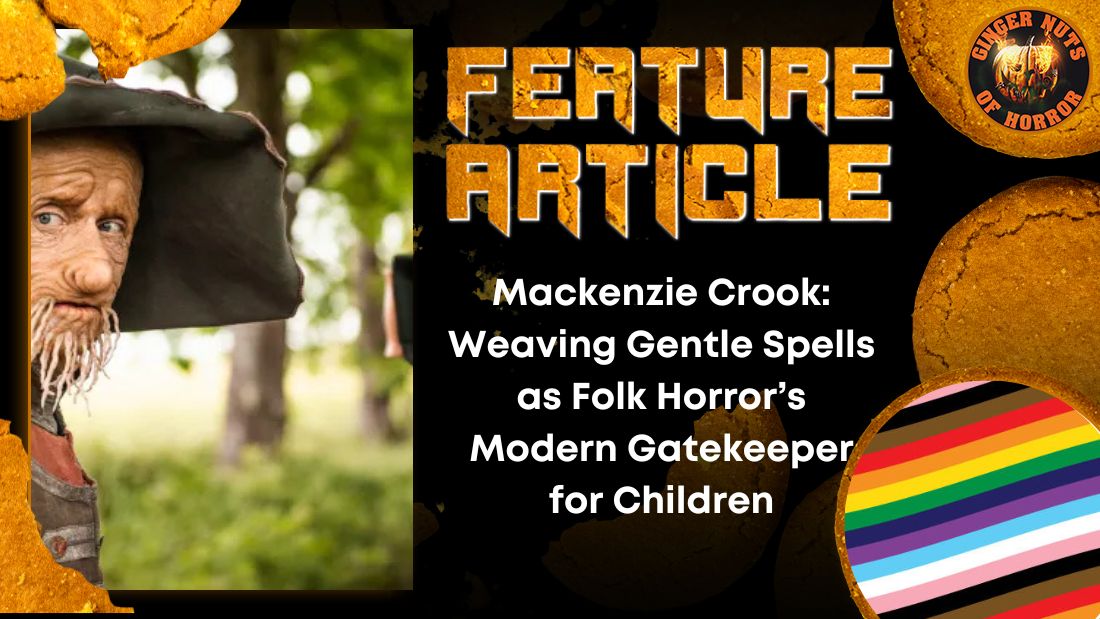

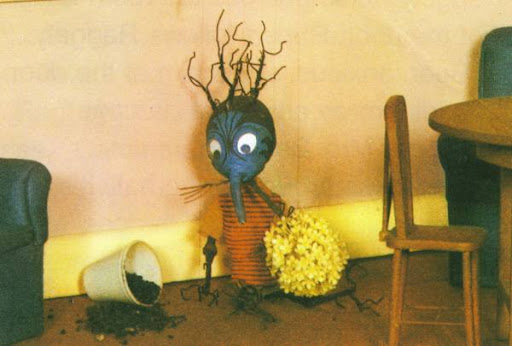

Crook’s unique approach lies in his signature blend of warmth, melancholy, and subtle surrealism. He does not horrify; he haunts with a soft touch, consciously gentling the very strands of folk tradition that earlier children’s media could accidentally render terrifying. This is most evident when contrasting his work with a series like the 1970s Rupert Bear animation, which, for many, served as an unintended gateway to unease. Where Rupert’s world was nominally sunny, its animation, with expressionless faces, oddly still backgrounds, and jerky motion, created a deeply uncanny atmosphere. Characters like Raggety, the wild, root-like man of the woods, were textbook folk-horror archetypes: primal, earthy spirits living on the margins of a seemingly idyllic community.

Yet, presented without Crook’s emotional context, Raggety could feel simply eerie, a symptom of the show’s pervasive “folk horror of the nursery.” Crook’s 2018 revival of Worzel Gummidge directly engages with this same tradition but recalibrates it. His show is playfully underpinned by what fans describe as “pure folk horror,” retaining the original’s eerie foundation, a world of sentient scarecrows and the shadowy supernatural judge, The Crowman, a figure kin to Raggety in his earthy mystery.

However, Crook presents it as a “friendly nightmare,” where such ritualistic figures of the land exist in a clear context of friendship, responsibility, and seasonal repair. He takes the latent, unsettling energy of the old folk archetype and illuminates it with heart, transforming what was once a source of subconscious creepiness into a symbol of connection and custodianship.

Similarly, Detectorists, a comedy about two men with metal detectors, represents a form of ‘Wyrd TV.’ It trades terror for a “haunting eeriness,” steeped in the folk horror importance of landscape. The fields of Essex become a place where the past constantly whispers. Crook’s upcoming project, Small Prophets, solidifies this trajectory. Involving alchemy, prophesying spirits, and a search for a lost loved one, it engages directly with the folk horror theme of arcane rituals practised in mundane settings, here, a DIY store worker’s shed.

Crook’s method is distinct: he softens the edges of classic folk horror, removing violence and cultish terror while retaining the central mysteries. He finds magic in the mundane, insisting enchantment is buried in everyone’s backyard. Most importantly, he prioritises heart. The supernatural is always in service of human stories, friendship, loss, belonging, and love. The “wyrd” becomes emotionally resonant rather than simply frightening.

This gentle approach places Crook within a long and rich tradition of British creators who used children’s television as a conduit for the uncanny, yet he occupies a unique point on a broad spectrum. Where Crook is a guide through emotional resonance, other artists have opened different psychological gateways.

The Pioneers Before Crook – A Spectrum of Wyrd

Mackenzie Crook’s work exists within a long and rich tradition of British creators who used children’s television as a conduit for the uncanny. His gentle, character-led approach represents one point on a broad spectrum, with other significant artists ranging from the masters of cosy disquiet to the purveyors of outright terror. Comparing Crook to his predecessors reveals not just a lineage, but the different psychological paths a young viewer could take into folk horror’s peculiar heartland.

Oliver Postgate: The Grandfather of Cosy Wrongness

If Crook is the kindly modern guide, Oliver Postgate was the original storyteller by a crackling hearth, whose tales held shadows that danced just beyond the firelight. Working from a repurposed pigsty with animator Peter Firmin, Postgate created worlds that were the epitome of homemade charm, yet were laced with what is often described as a “cosy wrongness”.

His shows were gateways not through plot, but through atmosphere and primal aesthetic. Pogles’ Wood (1965-68) is explicitly described as “stop-motion folk horror”, featuring a magical, possibly sinister wood just beyond a family’s garden. Bagpuss (1974), with its saggy cloth cat and sepia-toned shop for lost things, radiated a “gentle melancholia”. It’s folk music, performed by former political folk activists Sandra Kerr and John Faulkner, rooted in a genuine, earthy British folk tradition. The Clangers (1969-70), with its knitting-needle aliens and Soup Dragon, presented a world under constant threat from the sharp, metallic intrusions of human technology, a “sly rebellion” against the Space Age’s cold progress.

Postgate’s genius was to make the atavistic feel safe. The terror of ancient stones (The Clangers once built something resembling Stonehenge), the mystery of the deep woods, and the melancholy of forgotten things were all presented in a handmade, knitted, and whistled package. His warm, authoritative voice was, for a generation, “the voice of comfort, the voice of story itself”. The gateway he opened was a subtle one: he didn’t teach children to be afraid of the old, strange world, but to feel a nostalgic, protective fondness for it, a foundational emotion for much folk horror.

Look and Read: Dark Towers – Terror by Curriculum

A more direct and institutionally sanctioned gateway came from the BBC’s educational series Look and Read. Its 1981 serial Dark Towers, written by Andrew Davies, was a masterclass in embedding supernatural chills within a literary lesson. It functioned as a gateway through scholastic adventure.

For children in British classrooms, the terror of Dark Towers was both thrilling and legitimate; it was part of the school day. The story of Tracy and Lord Edward Dark trying to save a crumbling mansion from treasure hunters, aided by a friendly ghost, was punctuated by genuinely frightening moments. A contemporary rewatch notes it caused a “nightmare epidemic” in its original run. This was not an accidental scare, but a deliberate tool to engage young minds.

The gateway here was framed: the supernatural was presented as a puzzle within a narrative to be decoded, much like the vocabulary words taught between episodes. It made the eerie feel like a subject to be studied and understood, blending the thrill of a ghost story with the satisfaction of learning.

Children of the Stones and the Uncompromising Gateway

At the far end of the spectrum lies the uncompromising intensity of Children of the Stones (HTV, 1977). This serial did not gently usher children toward folk horror; it pulled them through its stone circle and into its heart. Often described as “the scariest children’s series ever made”, it is a direct, YA-version of The Wicker Man, blending pagan ritual, psychic forces, and cosmic horror.

Its gateway effect was one of full immersion. It presented all the core tenets of the genre without dilution: a secluded village (filmed in the authentically eerie Avebury stone circle), a sinister cult of conformity led by a magnetic leader (Iain Cuthbertson), and the outright supernatural possession of the community. Sidney Sager’s chilling score, a dissonant mix of atonal instrumentation and wailing chorus, was a character in itself.

For its young audience, the experience was formative and visceral; reviews from those who saw it as children recall being “far too young and it certainly scared me,” and note its “disturbing” and “terrifying” qualities. This was a gateway that led straight into the genre’s most disturbing chambers, trusting children to grapple with themes of existential dread and loss of self.

I Don’t Want to Go to Nutwood City Limits

For this writer, the seemingly innocent world of Rupert Bear, particularly the 1970s TV adaptation, was a source of deep-seated unease, with the character of Raggety—a wild, root-like creature of the woods, epitomising its creepy charm. The animation, with its limited, fluid motion, flat yet vivid colours, and oddly expressionless character faces, created an uncanny valley of childhood storytelling; the idyllic landscapes of Nutwood felt strangely static and vacant, as if the cheerful adventures were happening on the surface of a deeply strange and watchful world.

This taps directly into the subtextual, “folk horror of the nursery” that Mackenzie Crook consciously refines. Where Rupert accidentally evoked terror through its aesthetic, making the familiar forest feel eerily sentient, Crook intentionally takes similar folklore archetypes (the Raggedy man of the woods finds a kin in Crook’s earthy, ritualistic Crowman) and renders them with warmth and emotional clarity.

He gentles the very wyrdness that Rupert‘s unsettling style amplified, transforming latent fear into safe wonder, thereby bridging the gap between a child’s accidental shudder and a guided, heartfelt encounter with the magical landscape. It’s a reminder that the gateway isn’t always marked by witches and stone circles; sometimes it’s hidden in the sunny, yet strangely vacant, streets of Nutwood.

Mackenzie Crook’s contribution is to refashion this complex legacy for a 21st-century audience. He synthesises Postgate’s heartfelt warmth, the narrative engagement of a Dark Towers, and the reverence for landscape seen in Children of the Stones, while filtering out their most frightening elements. He replaces terror with yearning and cultish horror with community. In doing so, he ensures the ancient, weird soul of the British landscape continues to whisper to new generations, not as a threat, but as a fragile, magical secret waiting to be cherished and protected.

Crook is less a showrunner and more a gentle folkloric guide, crafting a unique and vital path into Britain’s folk soul where the first encounter with the “wyrd” is one of wonder, warmth, and profound connection.

Why Ginger Nuts of Horror is the #1 Resource for Horror Fans

Unmatched Depth & Legacy in Horror Books

Reviews: With 17 years of reviewing horror, we offer an unparalleled perspective. Our reviews expertly guide you from mainstream bestsellers to under-the-radar indie gems, helping you find your perfect, terrifying read.

Exclusive Access to Horror Authors: Go behind the scenes with in-depth interviews that reveal the minds behind the madness. We connect you with both legendary and emerging horror authors, exploring their inspirations and creative processes.

Award-Nominated Authority & Community: Founded by Jim McLeod, Ginger Nuts of Horror has evolved from a passion project into an award-nominated, essential horror website. We are a global hub for readers who celebrate horror literature in all its forms, from classic ghost stories to the most cutting-edge dark fiction.

Experience the Difference of a Genre-Dedicated Team

What truly sets us apart is our dedicated team of reviewers. Their combined knowledge and authentic enthusiasm ensure that our coverage is both intelligent and infectious. We are committed to pushing the genre forward, consistently highlighting innovative and boundary-pushing work that defines the future of horror.

Ready to dive deeper?

For horror book reviews you can trust, a horror website that champions the genre, and a community that shares your passion, Ginger Nuts of Horror is your ultimate destination. Explore our vast archive today and discover why we’ve been the top choice for horror fans for over 17 years.