Introduction

- Introduction

- Silent Hill 2 (Remake): Sometimes, It’s Nice To Be Wrong, A New Year Special My Life in Horror

- As before, atmosphere is king;

- Not so Silent Hill 2.

- And here’s the kicker: We never will.

- This conspiracy between the work and its audience’s imagination is essential and unique;

- For the longest time, the game is vacuously, soul-suckingly empty.

- Even in this first and most minor of encounters, there is so much to unpack:

- Counterpointed to Pyramid Head, we have a more insidious factor in the form of Maria:

- Despite ostensibly becoming an antagonist by the Silent Hill 2’s conclusion -depending on which path you take-, she maintains an ethos of sympathy, even at her most monstrous:

- This complexity is manifested in other characters, too; even those that may or may not be projections or expressions of James’s psyche:

Silent Hill 2 is a groundbreaking entry in the survival horror genre that has captivated gamers since its release. With its haunting atmosphere, psychological depth, and intricate storytelling, it explores complex themes of grief, guilt, and redemption. Set in the fog-shrouded town of Silent Hill, players take on the role of James Sunderland, a man searching for his deceased wife, who mysteriously calls him to the town. As players navigate this unsettling landscape, they encounter nightmarish creatures and confront their own inner demons, blurring the lines between reality and illusion. In this article, we will delve into the elements that make Silent Hill 2 a defining title in horror gaming and examine its lasting impact on the genre.

Silent Hill 2 (Remake): Sometimes, It’s Nice To Be Wrong, A New Year Special My Life in Horror

Given the unmitigated litany of disaster that preceded its release, we might be forgiven for assuming the worst of Bloober Team’s remake of the legendary Silent Hill 2. You may recall my cynicism regarding the affair from an earlier article taking a broader look at the franchise (an article in which I promised I’d very publicly eat my words should the game turn out to be worthy at all).

Well, here I am, having worked my way through the entirety of the remake, in a state of the most pleasant and sincere shock.

Bloober Team -a small horror studio who’ve found moderate success with psychological horror ironically inspired by the original Silent Hill entries- have knocked it into the outer-atmosphere.

From the off, it’s clear they understand the nuances that made the original game so iconic; the felicities and details of environment and atmosphere, the subtle storytelling, the suggestive dialogue and lack of exposition. Everything that’s essential to the original is here and beautifully rendered, whilst many of the less-pertinent elements have been judiciously side-lined or cut entirely (the introduction of the “monsters” in the original was arguably too early and too overt. Here, the game allows the player to get to grips with the atmosphere and the town itself before introducing the first encounter in a particularly witty, beautifully paced set-piece).

As before, atmosphere is king;

So much of Silent Hill 2 occurs ambiently rather than overtly, through sound, minor visual cues, via a less-definable sense of the uncanny that Bloober have captured and distilled to a pure essence of psychological horror.

The nature of Silent Hill’s horror is an evergreen subject amongst the series’ fans, its qualities endlessly examined, debated, dissected. Speaking personally, what distinguishes Silent Hill from so many of its “Survival Horror” contemporaries is a certain degree of restraint and sophistication:

The likes of Resident Evil are overt, deliberately “B-movie” in the scares they provide: Whatever threat exists in the game’s world is literal and physical; a direct danger to well-being (usually manifested in some undead horror or genetically altered abomination).

This is not the case in Silent Hill 2. Whilst physical threats exist in the town, they’re tertiary to the less-defined, pervasive sense of abstract, spiritual decay and corruption that exudes from every inch of the setting. The -comparatively- small Bloober Team, responsible for such contentious works of psychological horror as Layers of Fear and its sequel, clearly understand this on an intimate and profound level:

Horror in the Silent Hill 2 remake is, first and foremost, ambient; the preternatural quiescence of the -seemingly- abandoned town, the subtle signs of corruption and decay that gradually escalate as protagonist, James Sunderland, descends deeper and deeper into a Hell of his own making. . .It’s a masterclass in slow subtlety, in gradual cultivation of atmosphere.

The opening of Silent Hill 2 alone is a master-class in the cultivation of tension: As we guide James through the fog-bound outskirts of Silent Hill, the elaborate soundscape hisses and chatters with ambiguous confusion: Sounds that might be natural or environmental interspersed with fleeting whispers, the grind and shriek of strange machinery, the rustle and slow footsteps of something stalking just off the path, beyond sight. Layered beneath these environmental cues are numerous, low-level hums and vibrations, off-key monotones that recall malfunctioning hospital equipment and TV screens.

Every aspect of the opening sequence is designed to subtly unnerve, make the player feel isolated and alone in an environment whose off-key strangeness unsettles on a deeper level. And yet, nothing occurs in the opening sequence to suggest the nature of the town or the bizarre horrors it hosts. Every time it seems we might encounter something around the next corner, hidden within the fog, the game pulls back, refusing to fulfil the player’s expectation.

This is a remarkable quality, partially derived from the original game, but emphasised in the remake: Silent Hill’s quintessential horror is gloriously intact here. Apart from the opening, which is a delirious slow-burn, there are numerous instances in which some abomination or monstrosity could lurch out of the shadows, but doesn’t, leaving the player unsettled and confused, wondering what might happen, from which direction fright or threat might come.

Silent Hill 2 often leads players to assume that something is about to happen, leading them primarily via its unparalleled soundscape into dark and insalubrious recesses, only to pull back, leaving them at the bleeding pinnacle of tension. The deliberate denial of an expected pay-off is wonderful on so many levels:

Firstly, Silent Hill 2 flies in the face of video-game horror convention, and certainly the “Survival Horror” sub-genre from which it’s derived. In the example of its contemporary, Resident Evil, scares are more prescribed and immediate: The nature of its horror derives from familiarity with certain tropes and rhythms redolent of the genre. In Resident Evil, when you hear a monster groaning or growling in the dark, there’s going to be a monster in the dark.

Not so Silent Hill 2.

Take, for example, a set-piece that occurs shortly after the events in Brookhaven Hospital (roughly the mid-way point of the game):

Having been hounded through a twisted hell-scape version of the town, James finds himself wandering into the darkness of an immense tunnel. Immediately, something feels amiss: The quiescence is odd, given the raucous, industrial cacophony of only a few moments ago. Familiarity with the rhythms and structures of horror video-games primes us for a jump-scare; the emergence of something immense in the dark. But nothing happens. The deeper we wander, the further the tunnel goes, the deeper the darkness gets. The darkness itself seems preternatural; it closes in dense and cloying around us, the feeble torch we carry penetrating barely a foot in all directions. Then, something does happen.

But not what we’re primed to expect:

Our radio -one of the most brilliant mechanisms for inducing tension ever conceived in a video game- emits spurts of static, indicating the proximity of something awful. James brandishes a weapon, as he does whenever there are monsters near. In the distance, but far too close for comfort, something IMMENSE clangs and lumbers, our only indication of it the sounds it makes on the rusted iron ground. Try as we might, panic as we do, we see not even a silhouette; no trace of it, no matter how terrifyingly close it draws.

And here’s the kicker: We never will.

It’s the subtle genius of Silent Hill’s peculiar species of horror that it denies audience assumption (not to mention desire). That curious break in rhythm, the defeat of standard expectation, is itself unsettling, and excites anxiety in the most fascinating way.

Congruent with the psychosomatic nature of Silent Hill 2 as a setting, the game invites us to populate it with our own imagined horrors via subtle audio-visual cues:

We find ourselves blundering into rooms where something awful has clearly taken place, but the game provides only the merest hints of exposition, leaving us to imagine potential scenarios, tell the story for ourselves.

Earlier, during our sojourn through the Woodside Apartments, we return to a room recently explored to find an anonymous corpse slumped before a flickering TV screen. Bloodied, mercifully obscured by a soiled blanket, we have no clue as to what happened, how the body came to be there, save from context:

Subtle suggestions around the apartment that this is a case of suicide; one that echoes thoughts and inclinations James himself might’ve had. But these are only suggestions; whatever occurred isn’t detailed. The player is left to tell the story themselves.

A little later, James happens across a decrepit bathroom in which all the stalls are sealed. Exploring the area yields nothing save details of the environment’s decay. As we turn to leave, one of the stall doors begins rattling violently at our backs, and a woman’s voice can be heard, whimpering as though in the throes of violence.

The shock of it alone is terrifying, but, upon returning to the bathroom, we find nothing. No monsters, no corpses; nothing suddenly materialised out of the ether. Nor do we have any explanation for the moment save from context clues. Dread congeals based on curiosity and supposition; we are led to wonder what manner of atrocity occurred in the bathroom, what ghost or echo we just experienced.

These examples are emblematic of the species of psychological horror one finds throughout the game: Environments are ominous, oppressive and claustrophobic, often changing or distorting around the player to throw them off balance. Murk, shadows and inconsistent light play hideous tricks on the player’s imagination: Often, we trick ourselves into believing we catch glimpses of something in the distance, behind windows, moving in the darkness. And sometimes, we do. But more often, it’s a matter of our own minds tormenting us (just as protagonist James projects his own internal hell upon the town).

This conspiracy between the work and its audience’s imagination is essential and unique;

it demands a degree of immersion that makes the player complicit in both its horror and storytelling. The game even acknowledges this in its interface: More than once, James is given the terrible option to reach into some dark, ominous hole in the wall, a filth-clogged toilet, or to leap into openings in the ground in which only darkness is visible.

Rather than making these decisions a matter of a simple button-press, the game deliberately suspends the moment, forcing both James and the player to hesitate through a series of button presses that seem to subtly ask: Are you sure you want to do this? Whatever happens next is on YOU. It’s a beautiful, subtle detail that enhances the player’s complicity in James’s dilemma, and makes us responsible for any harm or horrors that result.

Throughout Silent Hill 2, we are directed by context clues and audio-suggestions; elements in the environment and soundtrack that have the effect of simultaneously distressing and shepherding us where we need to be. Occasionally, we hear things moving on lower floors or in adjacent room, doors opening in distant corridors or windows smashing nearby. All of this has the effect of maintaining the essential tension of the game whilst also ensuring we rarely -if ever- get stuck in the weeds.

Despite the overall complexity of the environments, from the eponymous town serving as an inconsistent “over-world,” to the various specific settings acting as “dungeons” in which the plot can be advanced, they are exceedingly easy to navigate, even when the game succeeds in its efforts to make us panic and blindly scrabble for shelter. In fact, the game actively uses that tension as a brilliant mechanism for driving us forward:

In contrast to the original incarnation, which necessarily took a more sedate approach to proceedings, here, moments of transition are often accompanied by an escalation in the strangeness and horror blanketing the town:

At intervals, the soundtrack ramps up, becoming a threatening, atonal dirge of industrial whirs, scrapes and clangs, while the iconic fog blanketing the town becomes agitated, swirling and dancing around us. At these points, the streets flood with creatures, the radio James discovers during one of his investigation screeching with static, warning of imminent threat.

We soon learn that fighting during these moments is a waste of effort and resources; the monsters are too many, and James often lacks the means of defending against so many simultaneously. The only option is to run, seeking shelter at whatever new spot James has marked on his map (another element that ensures things keep moving apace but which also enhances mystery: Why does James want us to explore this site or that? What might we find there?).

The sense of relief after crashing through the doors of such sanctuaries into relative calm and quiet is nigh-indescribable, rare moments of sincere recovery (that grow less and less frequent as the game progresses).

But never, ever expect this game to follow the precise patterns and traditions of its “survival horror” predecessors; it has no intention of doing so. Rather, it seeks to undermine our assumptions of the sub-genre at almost every turn:

In previous entries, and certainly in the original game, it was possible to make areas “safe” by killing all of the monsters in them. This is generally not an option in the remake: Monsters that were dead are capable of getting back up again. New monsters materialise in “clear” areas, meaning that fights must be picked and chosen carefully.

This is not a game that actively encourages violent encounters. In fact, it acknowledges the basic normality and vulnerability of our protagonist at every opportunity: James Sunderland isn’t a cop or ex-soldier. He doesn’t have especial skills, powers or knowledge.

He’s just a guy thrown into terrible circumstances. As such, combat is always fraught; deliberately ungainly and awkward, with many encounters best avoided altogether. That fundamental change in pace and dynamic from other “survival horror” titles makes the experience one of sustained dread and paranoia. Whilst James might ready a weapon every time his radio sounds, that’s not a cue to prepare for combat. Rather, it’s a much more effective, engaging approach to assess the situation and work out a strategy (more often than not, simply evading the monsters is the best solution).

It also enhances the sense of profound vulnerability that pervades the game; almost everything seethes with threat, from the environment to other characters. Everything is fundamentally unpredictable (even the most sympathetic characters in the game are occasionally sources of genuine danger, many of them becoming so as a matter of its corrupting, corrosive metaphysics).

The “monsters” in Silent Hill 2 have always been a step above the series’ contemporaries in terms of design and ethos. Rather than simply being aesthetic obstacles to overcome, they are densely symbolic phenomena that demand to be “read” in the manner of a text. As such, their horror is of a more disturbing, intimate species: These entities don’t merely mean James harm; they are manifestations and reflections of his own inner-demons, the monsters haunting his poisoned psyche that the eponymous town has teased out and made flesh.

The presentation of the monsters is so much more sophisticated in this remake than the original game: Here, their occurrence is suspended and suspended, leaving only fleeting glimpses and suggestions before the first makes itself known in a notably horrible set-piece.

For the longest time, the game is vacuously, soul-suckingly empty.

The quiescence suggested by its name becomes that of abandonment, isolation; a cemetery-silence. It comes to the point that the violation of that silence and emptiness becomes a point of horror in itself; desecration of a strange and unhealthy purity.

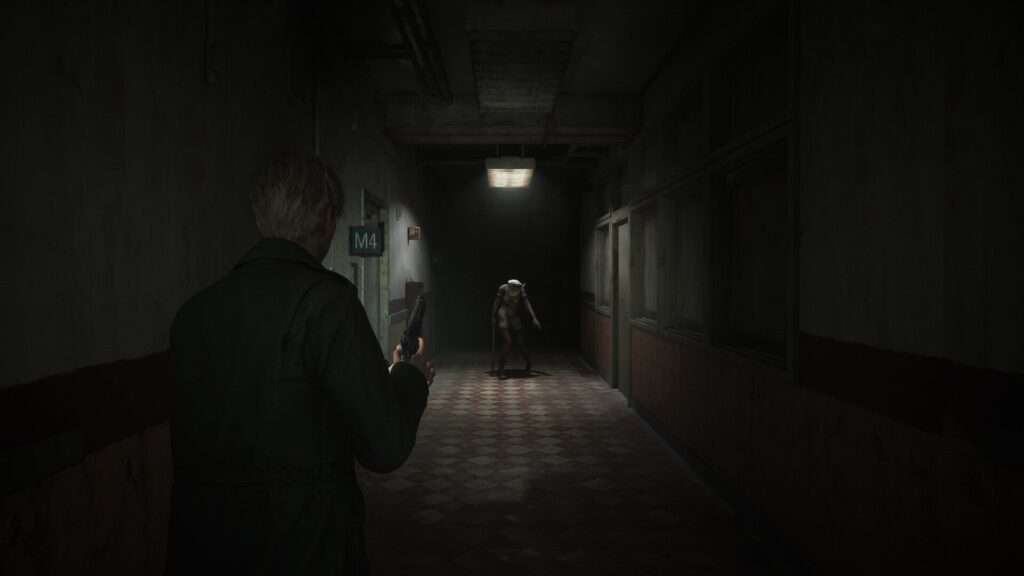

Before the first “monster” occurs, we glimpse its shambling, deformed silhouette off in the fog. James, of course, mistakes it for a person, as most of the “monsters” in the game are vaguely humanoid. Giving chase, he follows trails of clotted blood and filth through alleys and back-gardens, catching the most fleeting suggestions of the thing before it darts out of sight.

It’s in one of Silent Hill’s abandoned, decrepit homes we finally come face to face with our quarry: A wheezing, moaning, wounded entity, its lower body that of a naked, filth-smeared woman, its upper-body wrapped around in a straight-jacket of flayed skin. From its groin to the middle of its forehead gapes a wound that should be terminal, through which it vomits streams of filth at random intervals.

The creature is not only shocking by the mere fact of its existence, but also by nature of its design: This is not some familiar, horror-movie monster or new take on an old cliché. It does not derive from traditions made iconic by the likes of Universal Studios or Hammer Horror; this is closer to the idiosyncratic disturbia offered up by Lynch or Cronenberg, entities whose forms and natures are determined by the sicknesses they reflect.

So, the creature is sickly and wounded, oddly pathetic in its wretched condition, but also threatening in the way of something blinded by pain, rabid with suffering. What harm it inflicts seems to be random and instinctive rather than targeted, as though it’s almost appealing to James for mercy.

Even in this first and most minor of encounters, there is so much to unpack:

Firstly, the sickly, wounded nature of the creature recalls James’s impressions of his wife, Mary, in her last days (when unspecified disease ate away her last vestiges of dignity). The creature’s bound, straight-jacketed design speaks of smothering circumstances; a condition that can’t be escaped, but also recalls severe mental illness, redolent of insane asylums and institutions. Its principle mode of attack -the streams of effluent it vomits up- once again recall Mary’s less-savoury symptoms but also -symbolically- the awful, pejorative-strewn rages she fell into in the fever-washed fugue of her last days.

Like so much in Silent Hill 2, the creature demands analysis as much as it inspires panic. Fascination wars with disturbance in both James and the player, the violence we do to it rendered oddly unsavoury by dint of its pathetic condition.

Unlike many similar “survival horror” titles, Silent Hill 2 induces a subtle shame in the player for the violence they do: Most of the creatures we encounter already seem wounded or wretched, their behaviours towards us accusatory or defensive rather than outright aggressive. This is emphasised to the power of N when we realise that they are products and projections of James’s psyche: He is responsible not only for their states, but their unwanted, unasked for existence. The horror and violence between player and “enemy” therefore becomes distressingly intimate; self-dissecting, self-excoriating. James’s horror and loathing for these creatures is multi-dimensional: He doesn’t just fear and loathe them for their abominable natures, but because they reflect the abominable in him.

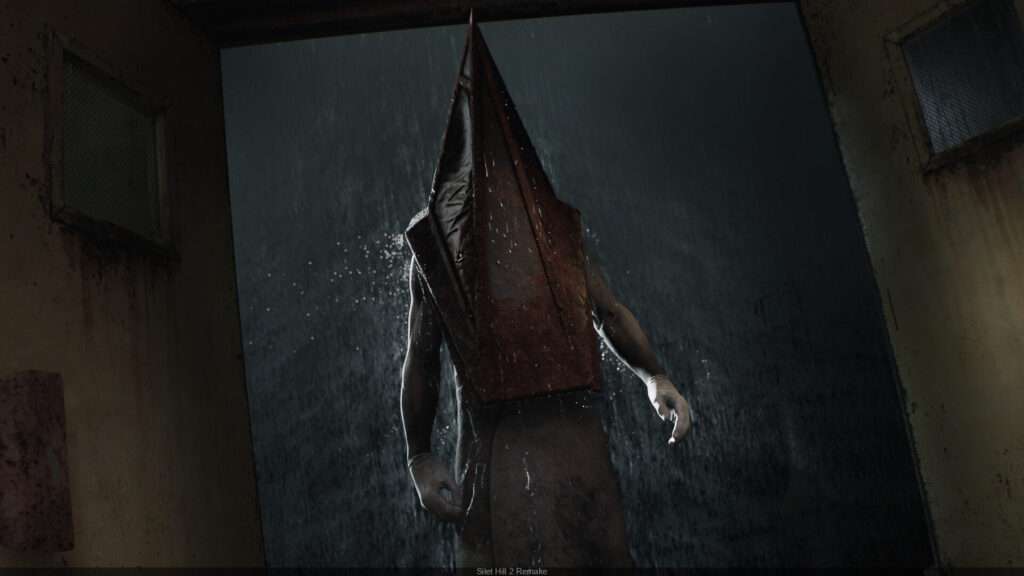

This factor finds ultimate expression -and, fascinatingly, contrast- in the most iconic entity in the game’s menagerie: The rapine pillar of masculine violence the video-game playing public have christened “Pyramid Head.”

The introduction of the entity is a master-stroke in subtle horror. Entering a darkened corridor of an apartment block, we glimpse an ominous red glow in the distance. Our radio blurts static, warning us of impending threat. Given no other option, we cautiously approach, the atmosphere growing denser and more foreboding with every step. At the end of the corridor, we’re stopped by a series of rusted metal bars. Beyond, almost motionless in the darkness, stands the immense, muscular bulk of a creature whose head is encased in a rusted metal pyramid.

The overt threat of the creature -with its scarred, naked musculature, its butcher’s apron and the tangible aura of violence it exudes- is belied by its state of unsettling calmness. The entity doesn’t threaten, doesn’t gesture or growl; it merely stands and observes.

It’s a beautifully unsettling, almost uncanny moment, in which we’re enjoined to wonder: What is this thing? Why has the game framed it in such an ominous, significant manner?

When we eventually find our way to the other side of those bars, its absence is almost as chilling as its proximity.

The next time James encounters Pyramid Head is when we begin to understand his import, but much can be gleaned from his truly spectacular design: Alone amongst the menagerie of Silent Hill 2, Pyramid Head is overtly and brazenly masculine; his scarred musculature is a stark contrast to the slender and feminine monsters we’ve encountered thus far and that infest the rest of the game.

Furthermore, he’s notably phallic in nature, both his helmet and the immense blade he carries redolent of Freudian imagery that only deepens as the game progresses. His state of blind watchfulness, his strange fascination with James, suggests a deeper connection, a more intimate relationship than with most of the other entities. Much can be gleaned by merely observing the creature (if you have the stomach to do so).

But it’s the second encounter that truly cements this entity’s nature; a sequence that has been refined and enhanced in the remake with reference to that very symbolism:

Entering a derelict apartment of no particular note, James is disturbed whilst exploring the kitchen by one of the feminine “torso” monsters (one of the more disturbingly sexualised of its ilk) that’s hurled on the floor by some unknown agency.

Hiding behind a wall, James watches as Pyramid Head grasps the creature by one of its limbs, treating it both like a piece of meat and the victim of some impending violence. Managing to hide himself in a nearby closet, James watches, appalled, as Pyramid Head emulates sexual violence with the creature (for all his overtly phallic nature, Pyramid Head himself doesn’t appear to be endowed or have sexual definition).

The moment is both profoundly disturbing but also one of revelation: It demonstrates that these “monsters” are far more than our standard video-game adversaries: They are not exclusively violent and hostile towards James, but have their own strange interiority; a sense of identity that stretches beyond being mere obstacles to overcome.

In Pyramid Head’s case, we’re presented with an entity that exhibits powerfully male dominion and physical violence towards the more female monsters he shares space with. Bound up within him is a freight of sexual repression and denial that finds expression in the most hideous and violent of ways. In this regard, he manifests that part of James that resented his wife, Mary, for her illness and the sexual frustrations it incurred. This element of James’s psyche is also reflected in the disturbingly sexualised “Torso” and “Nurse” monsters.

But the entities of Silent Hill 2 are far from as simple as that; they are not reflections of clear or simple drives. Rather, they are myriad neuroses and frustrations bound together in imperfect, often tortuous marriage. Pyramid-Head’s hounding of James throughout the game is particularly pertinent: He is judgement, James’s repressed sense of guilt and self-excoriation over what he did to his wife in the extremis of her illness.

As such, the creature is relentless, violent and immune to any physical attacks he might deploy. In our first active encounter with the entity -some time later, in the “dark world” reflection of the apartment block-, we’re presented with an encounter that cannot be won, only endured and survived. James must dodge and evade the creature rather than fight it. After a period of time, the iconic Silent Hill siren sounds, the “dark” world recedes, and Pyramid Head simply lumbers away.

Later, the creature acts as a malevolent shepherd or “guide” to James, always turning up to harass him down the correct path, towards the confrontations that result in some degree of self-discovery. This is not to attribute positivity to the creature in any way: It is not a positive or constructive force. It lacks anything close to such awareness or intention; it merely does as its nature dictates at the appropriate junctures, which is often violent, aggressive and sadistic.

Indeed, if Pyramid Head serves as a kind of “shepherd” for James, it’s only in the bleakest, most nihilistic way imaginable. Pyramid Head loathes James with ferocious intensity because James loathes himself. His aggression towards James is born from James’s self-excoriating judgement over what happened to his wife Mary (and later, her doppelganger, Maria). If he does indeed facilitate James’s self-enlightenment on occasion, it isn’t out of any benevolence towards James, rather an abiding, undeniable imperative that he be made to suffer.

Pyramid Head is judgement; he is the manifestation of what James ultimately believes he deserves, but also every dark frustration, every moment of petty blame, cruelty and hatred he felt towards his wife for her illness and the slow decay of their lives together.

In that, the monster has more depth and resonance than many protagonists of lesser texts: It is a creature of reluctant, violent confrontation, whose survival -and ultimate defeat- relies on James facing and acknowledging the darkest side of himself. Only when he allows for that, acknowledges what it means, can he sincerely fight the monster (and even then, not necessarily defeat it).

Counterpointed to Pyramid Head, we have a more insidious factor in the form of Maria:

A woman James ostensibly meets whilst wandering the town, she’s an exact double of his dead wife, Mary. However, whereas Mary was retiring and domestic, Maria is flirty, sexy and dangerous. Whereas Mary was predictable, Maria is exciting. She dresses and reacts provocatively towards James from their first meeting, familiar with him in the manner of an old girlfriend. Interestingly, in every interaction, Maria is the dominant force: James doesn’t know how to respond to her, occasionally becoming frustrated with her forwardness and flirtatious nature. She is a Lynchian mystery, complex in terms of both her nature and place within the story.

Given Silent Hill 2’s psychosomatic nature, she’s clearly a projection of James’s psyche, but to what extent she’s aware of that, what she represents and what autonomy she enjoys are all up for question. The game is uniquely uninterested in providing easy or simple answers, and that love of complex symbolic mystery is embodied in Maria.

Like many characters James encounters, she seems simultaneously confused about why she’s present in Silent Hill 2 yet absolutely certain she belongs there. At times, her flirtatious, teasing nature seems almost antagonistic, whereas others she’s entirely sympathetic (there are moments when she becomes angry with James regarding his myopia over Mary, his inability to see beyond her). Like Pyramid Head, she’s an unwitting guide of sorts; one who manifests so, so much that’s contradictory in James, she herself is torn apart by her irreconcilable nature:

At times, she comports herself in a subtly antagonistic manner, seeming aware of what’s happening in Silent Hill 2 -and particularly to James- in ways even she can’t clearly articulate. Others, she’s very much another victim; someone inveigled by the town, lost in her own nightmare. Neither of these are entirely true or entirely play-acts; they are the roles James requires of her, that shift from moment to moment based on his psychological state. One moment, she’s afraid and vulnerable, the next a seductress, almost succubi-like. One moment, she reflects the Mary James knew in waking life, the next she manifests his most idealised fantasies of her.

In this, Maria may be one of THE most complex, fascinating video game characters in the history of the medium: She is a manifestation of the contradictory ideals patriarchy enjoins men to project and impose upon women: She is inconstant and frustrating because James’s requirements of her are inconstant and frustrating. What’s more, she isn’t always aware of that fact: Sometimes, the game provides subtle indication that she intuits a little of her nature and purpose. At times, she even has inchoate premonitions of the fate it has in store for her.

But she can no more apprehend or express that than a fictional character might the story in which they operate, the end it’s propelling them towards. Even when she makes that effort, James quietly coerces her towards her intended fate (understanding on some level that it’s necessary for his own healing).

Despite ostensibly becoming an antagonist by the Silent Hill 2’s conclusion -depending on which path you take-, she maintains an ethos of sympathy, even at her most monstrous:

She is tormented and torn apart by her own nature: Because of James’s psychological issues, she is fated to be murdered and mutilated over and over again, to facilitate his self-realisation and healing. But she is -or at least becomes- sufficiently aware and autonomous, thanks to the bleak metaphysics of the town, to ache for more than that:

If James does encounter her in the game’s closing chapters, she tries once again to give him what he wants, to be everything for him, no matter how contradictory. She sees in him a way out; a way of being more than his current state of mind prescribes. But even in this, she fails, and James is incapable of fulfilling her. She cannot live within the inconsistent bounds of his expectations; she cannot be both Mary and Maria, both wife and affair, saint and succubus. It tears her apart, and so, she becomes the only thing she can:

A monster. A manifestation of all James most fears in women, all he is most repulsed by. This is one of the final encounters James can experience in the game: The ultimate confusion of Mary and Maria, of his assumptions and prescription of womanhood.

Yet, even at her most monstrous, Maria is a victim: She should never have come to be, a manifestation of a man’s diseased mind, of patriarchal requirements that no woman, actual or imagined, can fulfil. In that, she encapsulates a core factor of Silent Hill 2’s horror; that of a mind turned against itself, of a fantasy grown diseased and unruly, seeking to break out beyond the skull in which it gestates.

The poetry of the encounter is sublime, providing, as it does, a means of final reconciliation for James: Through her, he realises that he’s been chasing a fantasy all along; an idea of his wife that conflicts with the lived reality, and he can’t live in that condition either. The only way out is to put that fantasy out of its misery, end its confusions and contradictions and allow Mary and Maria both some peace.

It’s a profoundly rare species of horror to find in the medium; a rich and complex affair that consists as much of sorrow and melancholy as dread or terror. The sadness innate is that of regret; of life upended and unravelled by cruel circumstance. James regrets not only what happened to Mary but also the death of the life he envisioned with her, that she manifested for him. A significant part of the game’s subtext is him coming to realise that fact and understand: Both Mary and the life he envisioned are gone, and nothing will ever bring them back.

In some versions of the ending, he is able to reconcile this and, perhaps, entertain a life beyond (perhaps even moving onto another plain of existence entirely). In others, he cannot, and ends in suicide, crashing the car that contains both himself and Mary’s body into Toluca lake, thus beginning the purgatorial round over again.

This complexity is manifested in other characters, too; even those that may or may not be projections or expressions of James’s psyche:

Here, the likes of Eddie -who, whilst interesting, was somewhat tangential in the original game- are implied to have much deeper significance to the over-arching story (it’s implied that Eddie might have been responsible for arbitrarily murdering James in the “real” world, not to mention numerous incarnations thereof in the cycles through which Silent Hill feeds him). Likewise, Laura, who is something of a foil for James in the original game, becomes another aspect of womanhood James has issues with:

She is the daughter he and Mary never had, that he doesn’t know how to communicate with and she yearns for. She is the little girl James most dreads, in his most sublimated fears: A fey and unpredictable creature who does not fit into his projections and which he cannot control.

Likewise Angela, arguably the most sympathetic of all the game’s characters; a woman who, despite her ostensible weakness, is James’s equal in Silent Hill, in that she is experiencing her own cycles, her own hells, over and over and over again. Whilst they might occasionally overlap, James is an intruder in her version of Silent Hill 2, and it’s made clear by the conclusion of her arc that she sees a very different state than James (even when they intersect, the pair of them project roles onto one another based on their own narratives:

Angela becomes a “damsel in distress” for James to save, whilst James becomes just another male victimiser for Angela). Their resolution lies in James realising he cannot help her; it’s not his role nor what she requires of him. We never see the conclusion of Angela’s story, though it’s heavily implied she isn’t ready to move on as James is, and so returns to the beginning of her own cycles, to begin anew.

A fresh element to the horror in this latest incarnation lies in a form of Ludo-Narrative; whereas the original game was a linear, contained scenario, the remake subtly suggests a system of metaphysical cycles, in which James endlessly resets and returns to the beginning after failing to achieve the reconciliation he seeks. Like many elements of the metaphysics, this is never stated outright, but must be inferred from a variety of context and environmental clues:

At intervals, James finds corpses in various states of decay and mutilation scattered around Silent Hill. Whilst it’s difficult to tell, given their conditions, close examination reveals a number of familiar features: Blonde hair beneath the blood, a brown leather jacket, blue jeans.

Almost every corpse the player encounters bears a startling similarity to James himself; may, in fact, be incarnations of James from previous cycles of the story. This has profound implications for both the setting and mythology: The remake acknowledges and incorporates the original game as another manifestation of the same cycle. Likewise, it means that James has been experiencing the same purgatorial rounds over and over and over again for a time that can’t be measured by conventional means. The existential atrocity of this is something even the original game didn’t offer; a bleak examination of how we contrive our own hells and inflict them on ourselves ad infinitum, in endless expressions of self-loathing masochism.

And this barely scratches the surface. There is so much to celebrate in this new incarnation of Silent Hill 2, I can barely keep the numerous ideas it consists of in my head, let alone express them adequately. This is horror so resonant, so intelligent, so deep and delirious, it leaves its audience emotionally ravaged by its conclusion. I am still in a state of shock at my own emotional reaction to its closing chapters; an experience I will treasure for as long as I recall it, and which will no doubt inform my preconceptions of what horror is capable of going forward.

To have that experience, to be still capable of it at this stage of the day, is wonderful. To know that there’s media out there with the raw power and artistry to shake me to my core. . .nothing makes me happier to exist than that, and I am very grateful to have been so, so very wrong in my previous pessimism.

George Daniel Lea 06-01-2025