Exploring Clive Barker’s Tortured Souls Toy Line

I’m aware that this is somewhat breaking the theme of previous articles in this series; for the most part, the toy lines I’ve explored have been notable for their targeting of child markets, yet consisting of profoundly graphic or horrific subjects.

This particular range was technically never marketed to children.

Though I will provide some anecdotal evidence that it certainly shared shelf-space with those that were: I recall first coming across these figures as an adolescent-verging-on-teenager, while I was still an enthusiastic collector of the likes of Transformers and various other toy franchises: they began to pop up along with many other Todd McFarlane-produced ranges in local toy stores (including the incredible Dragons range), as well as several video-game inspired figures aimed at older children and teenage markets.

Marking one of Barker’s semi-successful attempts to import his peculiar brand of hallucinogenic weirdness into another market and medium (you’ll find the man’s name on everything from films to video games, from written fiction to comic book series), the Tortured Souls are unmistakeably drawn from the same font from which Hellraiser and its Cenobites sprang; upon a cursory viewing, it would be entirely understandable to take the various figures -certainly from the first series- as renditions of Cenobites that never occurred in the original films.

However, though they share certain themes and imagery, the Tortured Souls are actually an entirely separate mythology from Hellraiser, playing on the cultural enshrinement of that franchise’s imagery (interestingly, there is also a Hellraiser range of figures that was released more or less at the same time as The Tortured Souls that is also well worth exploring).

The figures themselves consist of various (appropriately enough) tortured and mutilated anatomies.

Many of them are far, far more elaborate than any that have ever been realised on-screen. From the priestly surgeon Agonistes to the disturbingly angelic Lucidique, the figures are not only prime examples of the extremity that pours so readily from Clive Barker’s imagination but also the magnificent level of character and detail that McFarlane toy franchises have become infamous for.

These figures do not boast any particular “gimmicks” as such; there are no levers that activate kicks or functions, no rotating heads, screaming sounds or flying sparks. Instead, attention has been paid to every inch of their insanely wounded anatomies; every scar, patch of flayed skin, and exposed organ has a place in a wider composition that evokes character. The aforementioned Agonistes play a central role in the range’s mythology (purportedly the last creation of God.

As he wandered in a hallucinogenic daze on the seventh day of creation), he is at once a pitiably broken thing, mutilated and scarred to the Nth degree, his semi-surgical butcher’s garb bound and woven throughout his flesh, various chains and instruments woven throughout his body trailing from where they have been embedded. His face, most of all, evokes the sense of something profoundly traumatised: a knot of almost featureless scar tissue, a grimace of pain drawn wide by straps hooked through his cheeks.

Like the iconic Pinhead Cenobite, there is something profoundly captivating about Agonistes.

Something that evokes more than mere repulsion or disgust: a priestliness and nobility that bespeaks incredible age and power. It’s not the kind of “toy” that might immediately appeal to most children (certainly not the kind most parents would buy for them), but certainly one that sparks a degree of imagination, especially since his lack of gimmicks, articulation, and general stiffness as a figure requires it.

Barker’s input over the range is somewhat vague, though his aesthetic and penchant for the mythological is overt throughout: what is absolute is the story involving the Tortured Souls, which explores their natures and histories: each of the figures comes with a chapter of the story, usually involving the events that led them to become so traumatised, later collected in an exceedingly rare hardback volume that is well worth seeking out if you happen to be a Barker fanboy (for many, Tortured Souls: Tales of Primordium is the story that The Scarlet Gospels should have been).

Alongside the bizarrely awe-inspiring Agonistes, the original range contains Venal Aanatomica.

A blind and lumbersome creation of my favourite figure in the range, Talisac, or Doctor Talisac, as presented in the novella. Venal Anatomica, whilst superficially similar to Agonistes, is in many ways that creature’s antithesis: whereas Agonistes has a certain weary elegance about him, highly redolent of the original Cenobites, Venal Anatomica genuinely resembles something stitched together and wounded; a wounded giant that drags its broken leg behind it, whose blind eyes render it almost pitiable.

As for its creator, the gloriously elaborate Talisac, his figure is amongst the most ambitious in the original series, as he is not only a figurine but an entire apparatus from which he lies suspended: a gallows-like structure of blades, chains and drips, Talisac himself a naked and hideously mutilated figure suspended from hooks driven through the meat of his face…but perhaps the most disturbing aspect of the Doctor is the “surgery” he has performed on himself, making himself the “mother” to his own creations: from his swollen open belly hangs a bulb of clear plastic.

A make-shift womb in which gestates a creature born of his own flesh and apparent genius.

A creature that is also rendered in toy form as The Mongroid: easily the least human of the abominations this range boasts: a quadruped entity that seems to stalk awkwardly on four human limbs, its belly and lower regions split wide to expose an immense, crocodilian maw, which its apparent “Father” becomes all too familiar with, following its birth.

The original range also includes the lovers who are recreated by Agonistes’s genius and become mythic as a result: the semi-angelic Lucidique, who sports parodies of wings in the form of metal structures across which is stretched patches of skin flayed from her back, as well as a halo formed from a buzz-saw blade embedded in her skull and The Scythe-Meister; a creature fashioned from Lucidique’s would-be assassin and eventual lover; one that becomes a myth in itself within the ancient city of Primordium.

The original range is notable in that it consists of figures that evoke imagination on sight: there is something particular in their designs that begs certain questions: how did they come to be as they are? What do they experience in these states of extremity? Are they perpetually agonised? Is there some monstrous glory in their conditions? Again, themes that are familiar to almost all of Barker’s work but most popularised in the Hellraiser films and their various attendant media.

I certainly recall being fascinated by these figures as an adolescent.

At a point in my life in which I’d only just discovered Clive Barker as an author, these were items of necessity and obsession, a range that I collected with absolute passion and found myself weaving stories around of my own (not having access to the book at the time).

As for the second series, it sadly doesn’t come with any scraps of back mythology (though knowing Barker, each of the characters has an elaborately detailed back story), though there are some suggestions of their place in Primordium in the biographies on the backs of their boxes.

If anything, the second series of figures is even more elaborate and inventively horrific than the first.

Easily, easily the most notable in that regard is the horrendous Feverish, an immensely bloated man strapped to some form of operating table whilst an apparatus not unlike Doctor Talisac’s removes demonic foetuses from his slit-open belly. The figure, like many in the second series, is more a diorama in and of itself than a playable action figure; it contains a situation of absolute extremes and unparalleled horror that immediately evokes any number of questions: who is Feverish, how did he come to be so impregnated? Who is responsible for his current state? These questions may never have answers from Barker himself, but we, as his audience, can conjure and obsess over.

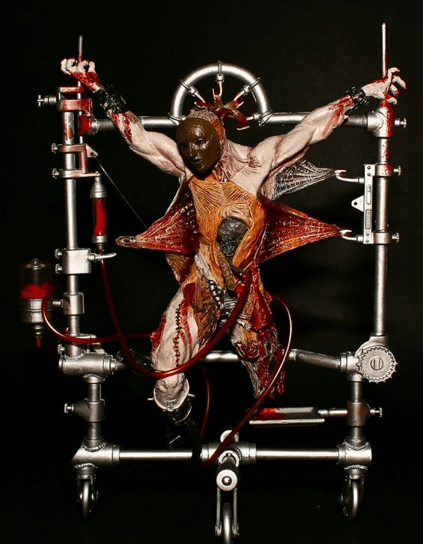

One of my favourites from the second series -one of the first figures I ever purchased from the franchise- is the martyr-like Moribundi, easily the most profoundly mutilated of the lot, whose brief snippet of back story suggests that he is exactly as he appears: a prophet of pain, martyred on “…the Altar of the World,” so as to save humanity from similar suffering: a wretched entity, Moribundi’s innards are almost totally exposed, much of his skin missing, allowing view of veins, musculature and organs, a removable mask hiding his distressingly flayed face, which is stretched back and pinned into place by a series of hooks.

Pierced through the hands and ankles, he is suspended on a mobile structure that looks to be part surgical apparatus, part altar, various drips and devices feeding through his flesh, sustaining him in his extremism.

Like all the figures in the range, Moribundi evokes a number of sensations.

Ranging from shock at his initial condition to a kind of melancholy, the character evokes a number of mythological archetypes, all of which serve as commentary upon something essentially wounded in the human condition: he is Christ on the Cross, Wodin on the World Ash and any number of tormented saviours; a synthesis of salvation through pain.

The second series also contains more oblique characters such as the far more “science fiction” themed Szaltax, a disturbingly female figure whose limbs have been variously torn out and replaced by mechanical augments, the upper half of her face shrouded in some visor-like device that lends her an arachnid aspect. Another of my favourites also derives from this series: the grotesquely comic Suffering Bob, an amalgam of two figures, one wasted and scrawny, the other grotesquely over weight, that look to have been surgically grafted whilst engaged in an act of unlikely sado-masochism: the immense, ambling figure holding the scrawnier by a series of leather leashes that attach to the leather mask swathing his head, the scrawnier figure’s torso emerging from its partner’s distended belly (or maybe its crotch) and scrabbling forward blindly on its hands.

The Tortured Souls are amongst some of the most disturbing, bizarre and beautifully conceived toys ever produced; examples of how minute detail and rigorous design work can create creatures that are not merely distressing or absurd or grotesque but are characters that evoke a sense of narrative engagement in whoever observes them.

This is a particular art when it comes to character creation in any format, but in toys, it is essential, as their purpose is to enflame and fuel burgeoning imaginations and ensure that they grow without stricture or compunction.