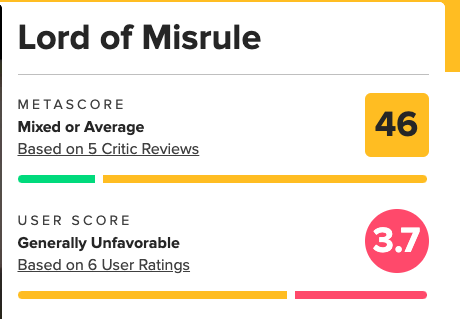

Lord of Misrule, folk horror, and why we’re still arguing about The Wicker Man

Please note that this brilliant article is directly tied to a second article on The Devil’s Bath, which will be published very soon.

[Heads up for mention of suicide and ableism. Also, murder, but you probably expected that one.]

Ahem. *Puts on mask.* My loves! My dears! I stand before you, a marked and witnessed Folk Horror Revivalist!

Today we’re going to talk about Lord of Misrule – a pretty minor film that won’t surprise you at all if you’re familiar with anything about folk horror. But by all things green, we’re going to go the long way round.

This review got away from me.

It’s monstrously long, and I’m not even sorry. Sometimes a film puts in so little thought that your own brain can’t stop thinking about it. If you like that sort of thing, this is the sort of thing you’ll like. If not, well, can’t be helped. Probably it won’t be your thing if you’re the kind of person who calls things ‘pretentious’ a lot either; I am an arty-farty person and it’s gonna show. Post a tl;dr somewhere for the engagement and we can part friends.

One thing I’m not pretending: I love folk horror. Worse, I write folk horror, or at least dark folk fantasy, which is why Jim allows me to review here. (And you should definitely read my books: they have cold iron, standing stones that won’t stand still, versifying pigs and a fiery Black Dog that eats landlords.) I am the kind of insufferable obsessive who has opinions every which way about folk horror; I am the ants at the picnic just trying to watch a movie with deer horns in it.

So if that’s not your idea of a good time, then I’m sorry, Little Read Reading Hood, but you were warned. Some people have a pet subject, and this is one of mine. And I do promise to try and skirt the line between enthusiast and purist, so I’m going to pull my biggest d*ck move here and now and from thenceforth it can only get better:

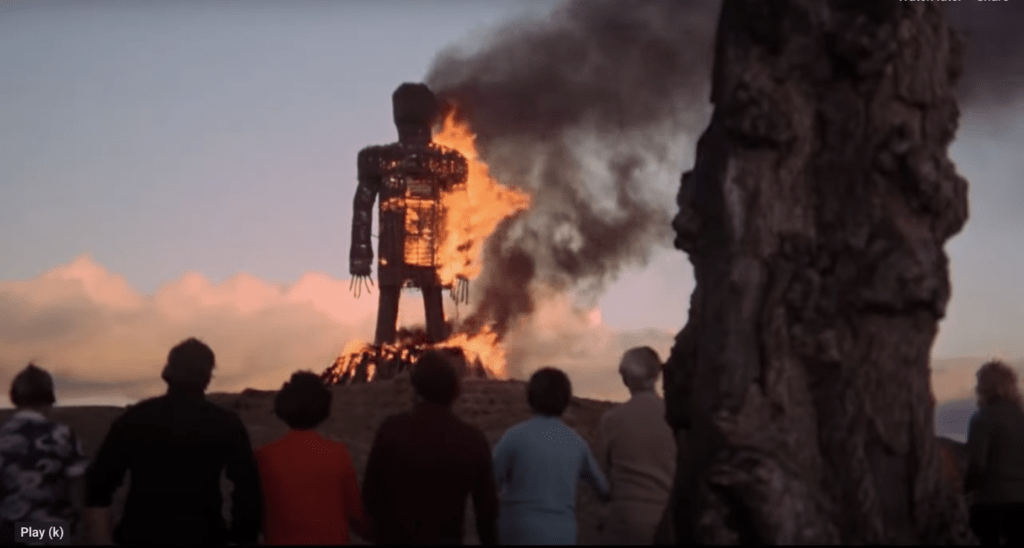

The film that most people think of when you say ‘folk horror’ is The Wicker Man (Robin Hardy, 1973).

At the end of that movie, they sacrifice the hero. Sorry to spoil it for you, but you’ve had fifty years to find that out. There are a lot of recent films that seem to think you haven’t, and if you don’t know it, then you’re going to be easy prey. It was a shock ending then; by now, it’s a genre convention on a grim, steady shamble into the wilds of cliché.

Now, I promise I’m not just spoiling a movie for the sake of it. Lord of Misrule is it’s one of those films where to understand the criticisms, it helps to understand the context – and you can’t understand the context without knowing about The Wicker Man. There are quite a few folk horror films like that, and this is really, really like that.

And that’s an interesting discussion, and one that folk horror enthusiasts often get into.

There are some films of which some some critics will say ‘This film is ripping off The Wicker Man’ as a negative – and others will say ‘Of course it’s influenced by The Wicker Man but critics need to stop comparing every folkish film to that.’ These are reviews that are trapped in the middle of an ongoing argument, and today, *doffs mask*, I’ll be your tour guide around that argument.

Lord of Misrule may end up slain upon the altar, so if you don’t want to hear bad things about it, fair warning. If you stand ten paces back it looks like folk horror: that’s its whole selling point. But it’s one of those films where the only interesting thing to do with it is to talk about the genre it’s attempting to fit in so you can understand why it fails in the ways it does.

So: what in the name of the fields and furrows actually is folk horror? Well . . .

Folk horror used to be an accidental genre, and now it’s a deliberate one.

Back in the 70s and 80s there were a lot of films and TV shows that used British landscapes and folklore to tell a chilling tale, and while the term was first used by Rod Cooper when reviewing Piers Haggard’s 1971 film The Blood on Satan’s Claw (beat that for a title), it was only after Mark Gatiss’s three-part 2010 documentary A History of Horror that the term really caught on. Before 2010 a film might be considered folk horror; after 2010 it could decide to be folk horror. Gatiss, basically, called to public attention that folk horror might be a thing, and a lot of people thought that sounded fantastic and went looking for it.

What are these influential films?

Well, the ‘Unholy Trinity’ of the genre consists of The Wicker Man, The Blood on Satan’s Claw, and Michael Reeves’s Witchfinder General (1968).

In The Blood on Satan’s Claw, an honest ploughhand accidentally unearths a kind of demon-thing that accumulates an earth-worshipping orgiastic cult around it. (If sexual assault is a painful subject for you, be aware that even the director later regretted some of the movie’s excesses. The performance is more cartoonish than naturalistic, but it’s a movie prone to getting carried away.)

In The Wicker Man, the kirkishly repressive police sergeant Neil Howie goes to the remote Scottish island of Summerisle to investigate the disappearance of a young girl, only to discover a neo-pagan community whose landlord revived ‘their joyous old gods’ a century ago by way of motivating them to work harder. Howie thinks they plan to sacrifice the missing girl to the crops, only to learn too late they plan to sacrifice him.

And in Witchfinder General, we follow the adventures of a nice young Roundhead soldier trying to rescue his sweetheart from the depredations of ‘Witchfinder General’ Matthew Hopkins, played by Vincent Price – a real historical figure, though if you read his writings you’ll see a specious little dork who didn’t deserve to be played by anyone that cool.

Horror rises from the furrows, or from witch-paranoia: we have old folk traditions and a dark history of worrying about them, and folk horror can go either way.

But that’s the basics, and if you come join us on the Folk Horror Revival Facebook page you’ll see all sorts of things being shared. It’s an eclectic scene because it was never planned by anyone.

So what counts as folk horror if it’s an accidental genre?

Well, there are theories and discussions and so on – Adam Scovell’s proposed ‘folk horror chain’ is probably the most widely accepted, and I’ll be going into that more below.

But the lovely thing about a genre with no manifesto is that you can go on vibes. All sorts of things can have a folk horror feel to them, and with no strict rules they can come to the party just the same as the officials.

One political note. Scovell explicitly set out to create a definition that wasn’t limited to European folklore, and that was a good point to make. Because the term originated around British films there are some who complain that it’s an overly-white genre. And indeed, there is a white-supremacist fringe who the rest of us abhor: the dauntless moderators of the Facebook page, by all accounts, spend a tiring amount of time getting rid of neo-fascists who can’t tell the difference between ‘folk’ and ‘volk’. We are grateful for their work.

But here’s the thing about folk horror: we’re all ‘folk’.

You think you’re an aristocrat? Well, forgive me if you literally are, your lord- or ladyship, but the truth is that if you’re an ordinary person then you are part of the folk culture of your particular time and place, whenever and wherever that is. There are films like Candyman (1992) that are considered urban folk horror, for instance: different setting from the Unholy Trinity, but a similar vibe. Folk culture is just what people do around these parts.

So if you’re interested in folk horror, you are not stuck in Britain, or even Europe. Do you want Senegalese folk horror? Check out Saloum (Jean Luc Herbulot, 2021, also on Shudder): three badass mercenaries get waylaid on a mission to Dakar, only to find the remote outpost where they land is run by a former warlord with connections to a terrifying Bainuk curse. Want Jewish folk horror? Check out The Vigil (Keith Thomas, 2019): a young New Yorker is approached by the Orthodox community he tried to leave behind and hired to keep watch over the body of a man haunted by a malevolent Mazzik.

Want Japanese folk horror?

Check out Ringu (Hideo Nakata, 1998, and if you’d rather watch the American remake then get out of my sight): a cursed videotape is circulating, and the older generation really should have listened to the warnings that if you play in the ocean the goblins will come for you. Heck, want white American folk horror? Forget the movies that try to ape European folk art; watch The Night of the Hunter (Charles Laughton, 1955) and shiver to the dark mythology of Southern Gothic Christianity with Robert Mitchum’s truly infernal preacher – or for a more recent example watch Jug Face aka The Pit (Chad Crawford Kinkle, 2013), which is heartbreaking and excellent and I’ll come back to it later.

So is folk horror all about May Day and Harvest Festival and the English countryside? Nope. And there are two big reasons why that matters. (Well, three if you include ‘Do not lend aid and comfort to white supremacists,’ but I’d like to trust that goes without saying.)

The first is just that it’s spoiling your own fun: every culture has folk traditions and can tell scary stories with them, and if you think it’s just about the flower crowns then you’re going to miss out on some really entertaining and/or chilling films. But the second is what we’re going to talk about today: a genre is more than its set dressing.

You can enjoy flower crowns if you like them; so do I, and even if I didn’t I’m not the boss of you. But to really enjoy the full delights that folk horror has to offer, then you should understand it in the broadest of terms:

Folk horror is a genre that uses what’s there.

Folk horror in its original form is to English culture not unlike what the Western is to American: like your ma always told you you should, it ate its leftovers.

There’s the financial practicality of it: drive out to Utah and you’ve got magnificent mountains right there for your tale of untamed lands where men were men. Drive out to Avebury or the Chiltern Hills or, heck, pretty much any old field or village, and you’ve got a plausible background for some dark superstitions. We have a lot of history around these parts.

Myth overlies the real world like spider sheets, glimmering eerie and blurring the harsh lines, and if you’re shooting in the right part of the real world that’s half your atmosphere work done for you by your location scout. Some genres happen because we can afford them: it was true of found footage, and it was true of folk horror back in the 70s and 80s.

But there’s also the other thing that’s already there: the myths themselves. That’s where folk horror really gets you – the realisation of how we’re already enmeshed. We grow up in the tales of our particular place, and if a spider tugs on just one thread of them, we feel the flex and spring of the whole web.

One of the best things ever said about folk horror comes from Terry Pratchett in Lords and Ladies, in one of his moments where he laughs and plays and jokes and teases and then wheels around like a clown with a plank on his shoulder and knocks you down with something absolutely correct:

—

People remember badly. But societies remember well, the swarm remembers, encoding the information to slip it past the censors of the mind, passing it on from grandmother to grandchild in little bits of nonsense they won’t bother to forget.

—

And that’s how folk horror hits you hardest, with ‘ancient fragments chimed together’ (Pratchett again).

So let’s come back to The Wicker Man. Did audiences expect the ending? No – but it was a shock ending, not a surprise one. The filmmakers drew a lot from James Frazer’s The Golden Bough, which might not be considered unimpeachable anthropology now but is certainly dug deep into our culture even if you haven’t read it. And Frazer was talking about a lot of other cultures you probably know ‘little bits of nonsense’ from even if you aren’t a scholar.

And what The Wicker Man used for bits were important.

Sure, they were attractive to look at, but what really mattered was that you felt your memory being tweaked. If you were of the right generation then you’d almost certainly participated in these rituals yourself back in your childhood – or at least an innocent version of them. Howie disguises himself with a Punch mask; you’d probably seen Punch and Judy puppet shows.

The final parade involves a hobby-horse costume; you’d probably ridden a stick with a horse’s head, and in Britain a ‘hobby-horse’ is what we call them. You’d probably played ‘Oranges and Lemons’, singing and chopping down with your arms; the Summerislanders do too, except they add swords. You might not have danced around a Maypole yourself but you’d probably seen one, and the Summerislanders have a whole worship built around its symbolism. So when it all came together in a horrible climax, it was horrible because it made sense. It made sudden, awful sense in a way you felt you should have seen coming. You were almost at home, and then you weren’t – or maybe your life had always had this invisible violent streak running through it. Like a trusted old dog turned rabid, your own culture leaped and bit you with poison teeth.

That’s what we go to folk horror for.

And that happens hardest when the focus is on the meaning rather than the trappings.

Because when people argue ‘Wicker Man rip-off’ versus ‘Wicker Man re-imagining’, that’s what they tend to be arguing: is there any actual meaning in this film? Does the plot and setting serve its own purpose? Terrifying cult, or cargo cult?

Of the Unholy Trinity, The Wicker Man is the one that most often gets brought up in accusations of ripping off, and the reason is that it had a plot that was genuinely startling once – but the key word is ‘once’. Witchfinder General is loosely inspired by real historical figures; there are plenty of movies to make about witch-hunters without having to focus on that one particular film. (I’d recommend tracking down Pablo Aguaro’s Coven, aka Coven of Sisters (2020), if you want a gruelling but great recent example.)

And The Blood On Satan’s Claw is just bonkers, honestly: it was intended to be an Amicus-style portmanteau film with several short stories happening in the same place, and they rewrote it rather hastily to make it a single narrative, and it shows. It’s a marvellous film in cinematography and music, and fans forgive the plot for being silly because it does atmosphere like nothing else on this green earth – but it is a silly plot, and anyone attempting a similar film today would be trying to make something a bit more coherent out of a beautiful mess. You can’t copy a structure that hardly qualifies as a structure at all.

But The Wicker Man scooped in a whole lot of cultural traditions and created a perfect plot with them, and it was a new kind of plot that depended on a twist ending. That’s very hard to ‘reimagine’ without the audience losing interest because they’re watching a mystery that arrives pre-solved.

So when a new movie plays on the same idea, here’s the question: has it grasped why that ending was so powerful? Or has it just decided that harvest festivals look cool and that human sacrifice is an exciting gimmick, and hoped that its obvious resemblance to The Wicker Man will either pass you by because you haven’t seen it or please you because you like more of the same?

Or, to put it another way: is it inspired by myths or movies? Is it drawing from the same well as The Wicker Man, or dipping from The Wicker Man’s bucket? Does it look any further back into our past than 1973?

Contemporary folk horror includes some heavy hitters.

I never could be bothered to take a side in the ‘elevated horror’ argument – storm in a teacup if you ask me – but quite a few of the best arthouse horrors of recent years have been strongly folkish. The Witch (Robert Eggers, 2015) is a favourite, and anything by Ben Wheatley is worth a look. Some really great work has been done by artists who know how to take old stories and knock you down with them. They know that our past is full of shadows, and they create their own plots and twists, and their films are disturbing and handsome and folk horror fans love them.

There’s also a lot of other films that . . . have a certain look. They have stag horns and trees and doubtful locals, and they talk about rituals and superstitions. But do they feel like half-remembered little bits of nonsense suddenly leaped into the foreground and reminded you that you were never safe? Not really. If you want something pretty then you can watch whatever you like.

But if you want to feel the real weight of folk horror then it’s not about the bells that jingle on the jester’s stick. It’s about the roots of the tree they cut the stick from, and the arm that swings the stick as it buries itself in your brain.

I swear we’re about to do an actual review, but just a final sidebar – because if I’m talking about modern folk horror then much though I’d like to, I can’t get away with pretending Midsommar (2019) doesn’t exist. So let’s talk about it, because honestly I don’t think it falls quite on either of those two stools, and there’s something instructive about that.

Midsommar is something unusual: a prestige film that also gets accused of being a Wicker Man rip-off. Most films with that accusation are pretty throw-away, but whatever else you have to say about Ari Aster, his films aren’t disposable. Yet Midsommar is very similar to The Wicker Man in plot, to the point where even its admirers sometimes regret it. A young woman called Dani (Florence Pugh) loses her family at the hands of her mentally ill sister; grief-stricken, she follows her douchebag boyfriend to rural Sweden with his anthropology student buddies, where they study the summer rituals of an apparently untouched pagan community called the Harga.

The Harga have lots of flower crowns and embroidered shirts and quaint murals, and of course their rituals turn out to be way more murderous than anybody expected and it ends up in human sacrifice. We all know the drill by now. The modern twist is that at the end, the Harga recruit Dani as a new member – possibly because, like them, she’s white and pretty and the kind of genetic material they want to refresh their stock. In support of this interpretation is that the Harga are genetically-minded: they sometimes deliberately inbreed to produce an ‘oracle’ child, in this case a boy called Ruben (Levente Puczko-Smith) whose mind, the Harga insist is ‘unclouded by normal cognition’. His disability is vague and, as is unpleasantly common in movies, played by an actor who has nothing to do with it; Ruben looks like this:

So it’s human sacrifice plus human breeding, and I’ve heard the well-argued defense that Midsommar is supposed to be an attack on white supremacy and the Harga are a parody of Aryan eugenicists. They murder visitors of colour and breed from white ones, but look what their genetic insularity leads to, folks! The real horror was the white supremacy we made along the way.

So – is this The Wicker Man with a bit about race thrown in? What to think?

Cards on the table first: I get genuinely upset by how Aster portrays people with developmental disabilities and/or mental illnesses. Dani’s sister is ‘bipolar’, and that’s the only explanation we get for her murder-suicide antics, and apparently we’re supposed to find that reason enough, and if you know anybody bipolar you’ll know it isn’t, at all. Ruben is less a character than a visual warning, the first sign that all is not as idyllic with the Harga as it seems – which only works if you think the presence of an atypical-looking child in a community is a sign there’s something wrong with it. (Tip: communities that include such kids in their daily life are, in the real world, less likely to kill you. Those are where the nice people live.)

And I have a kid with special needs. He looks more like Puczko-Smith than like Ruben, because what’s on the outside of your head and what’s inside it are two different things – and indeed, I was at primary school with a girl who did look a little like Ruben, and her mind wasn’t ‘unclouded with normal cognition’ in the least; she was bright and popular because she was just a nice ordinary child with a medical condition. And come to that, a kid with atypical cognition doesn’t have an empty, ‘unclouded’ mind either: there are always thoughts and feelings in a real special-needs kid’s head just like everybody else, but we never see Ruben shown as having any. As a prop, Ruben functions; as character, he’s just nonsense every which way you look.

When I watch Aster’s films I see my heart up on screen, set there as a scarecrow to disturb the audience.

I don’t see an argument against eugenics: I see a film that agrees with eugenicts that disabled people are disgusting and/or scary, and only disagrees as to how best to avoid creating any more. You think insularity is good because it creates good stock? No, in fact insularity is bad because it creates bad stock – but I’m not going to argue with you that good stock is an important goal. It’s probably going too far to call Aster a deliberate, card-carrying eugenicist – I wouldn’t go further than ‘casually ableist’ – but casual ableism is real eugenicist’s weightiest tool, and this kind of stereotyping has been criticised in movies for long enough that Aster has had ample opportunity to know better.

So yes, I hate what he does with my whole heart and I really begrudge admitting that he’s also lavishly talented, at least visually – but he is. I am temporarily setting aside my Mayday mask and gripping hard to my big-girl pants when I say this: Aster can direct. He can go fuck himself, but he can also direct.

However, in the context of folk horror there is an issue I’d be raising about his movies even if I liked him better. I love that folk horror is accidental enough to make gatekeeping pretty pointless, but this is one gate I do think has meaning:

Can you call someone a folk horror master when it’s never their own folklore they’re afraid of?

I don’t think you can.

And if that’s true, then Wicker Man rip-off or not, I personally wouldn’t class Midsommar as folk horror at all. It has pretty paintings and burning bonfires, but structurally it’s a cannibal movie: the colour scheme is pale, but our American heroes go off into a Darkest Elsewhere. As with disability, when it comes to culture Aster’s films are afraid of the Other. I’ll talk more below about how any modern European paganism is revivalist, but it’s notable that Aster chooses to imply otherwise: the primitivist cult of Midsommar have supposedly been practising their murderous traditions for centuries undisturbed, and it truly takes an American to think that’s a likely story in present-day Sweden. But it’s aesthetically necessary when the story you’re telling isn’t afraid of the deep horrors within its own history, but of bloody foreigners.

Midsommar has things to say about loneliness and indoctrination and so on, but in terms of cultural position it’s doing pretty much the same thing as Hostel (2005), which is showing crass American tourists what happens if they go too deep into non-Anglophone Europe where life! is! cheap! Hostel even nicks the famous ‘Willow’s Song’ from The Wicker Man for its soundtrack [worksafe link here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bRcwiA6hH7U], so it’s not as off-base a comparison as it sounds. Both watch like films where someone saw The Wicker Man and rather than thinking, ‘Blimey, my culture is darker than I knew,’ thought, ‘Man, good thing I don’t live over there.’ It’s a different kind of fear.

People sometimes call a film folk horror because of its trappings, and some of those films are essentially hollow. Midsommar isn’t hollow and isn’t just trappings, don’t get me wrong. Through gritted teeth I will admit it’s a well-made film, and it does have something to say other than ‘flower crowns are cool,’ and if some of those things are cruel then the films still have spoken to some people struggling with grief, and it’d be really crappy of me not to respect those people even if I don’t like the films. But if it isn’t empty, its core isn’t folk horror, at least as I’m defining it here. But I’m aware I may die alone on that hill.

On the hill of criticising Lord of Misrule, though, I may have company.

Are we ever going to talk about the actual movie?

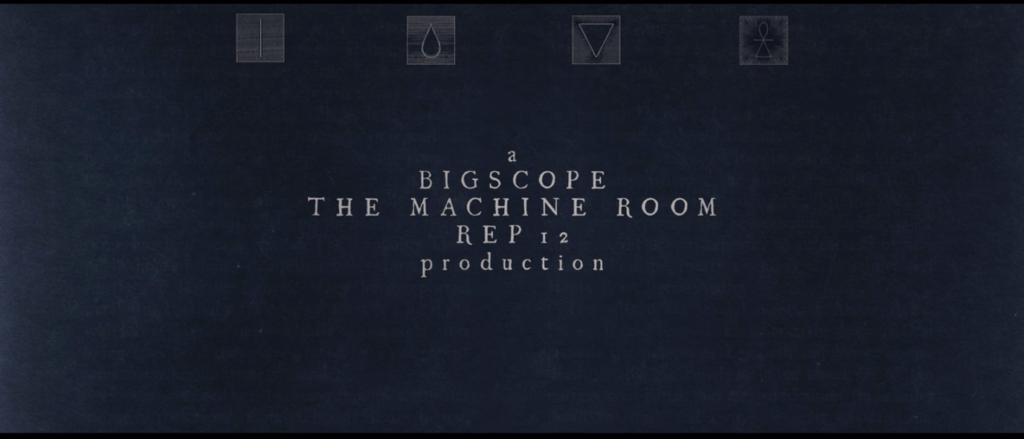

All right, all right. But having got this far, you’ll see why when I saw this for the credit sequence, my heart sank just a little bit.

Lord of Misrule is aiming for folk horror. It’s seen The Wicker Man. It’s seen Midsommar. Probably it’s seen The Ritual and Hannibal. It knows what it’s supposed to look like.

I don’t think it knows what ‘Lord of Misrule’ actually means – and no, this is not just being snotty.

If you’re going to do folk horror you need to know what folk traditions are, same as if you’re going to do a slasher you need to know which is the pointy end of the knife.

If you’re curious: the Lord of Misrule, known in Scotland as the Abbot of Unreason, was a historical tradition that went out around the time of the Tudors: over the Christmastide, a master of revels would be appointed in courts, grand houses and colleges, directing the entertainments, receiving mock homage, and generally being in charge of the fun. Normal proprieties were suspended and everyone enjoyed a season of Opposite Day where the serious was made fun of and the low were elevated – and then duly put back in their place after Christmastide. It’s a festive midwinter world temporarily set upside-down, and if you used that in a folk horror film you could do something really interesting.

Lord of Misrule is set not at Christmas but just after harvest time, and the Lord of Misrule does precious little ruling. There are supposed to be days of feasting and celebrating but we don’t actually see them; we see a single event where the ‘Lord of Misrule’ is a guy who turns up in a mask, makes a speech, and supposedly banishes the Spirit Gallowgog. Apparently the spirit blights the land – although later he’s considered a ‘spirit of the land’, and later he’s a demon worshipped by an old cult. Visually he’s red deer-skull mask, so I hope you enjoy that – and if you’re going to, I hope you haven’t seen too much recent folk horror because if you have then deer-skulls will, shall we say, not stun you with their originality.

Look, I didn’t like this film, that’s pretty obvious, but we might as well try to get something out of this review other than just complaining, so here’s what I’m going to do:

I’m going to use it as an example of why it’s hard to do an ‘accidental’ genre on purpose unless you also want to do something else.

Here’s the story. It’s harvest festival at the village of Berrow; our heroine Becca Holland (Tuppence Middleton, looking as pretty as everything else in this movie but giving a performance better suited to a cosy murder mystery TV serial) is the new vicar. She’s doing her best to serve a sparsely-attended church while also showing community spirit by joining the harvest festival and letting her daughter Grace play the ‘harvest angel’ while her husband works upstairs on an unspecified project and fails to keep a proper eye on Grace.

Exactly what the husband does is never clarified, and there seem to be some tensions in their marriage that are never really explored or explained. This happens a lot: it’s an hour and forty minutes of movie but characters are only very thinly developed, if at all, so when dramatic decisions happen at the end we just have to take the film’s word that it makes sense they’d do them. Anyway, that’s the family and they’re off to the festival.

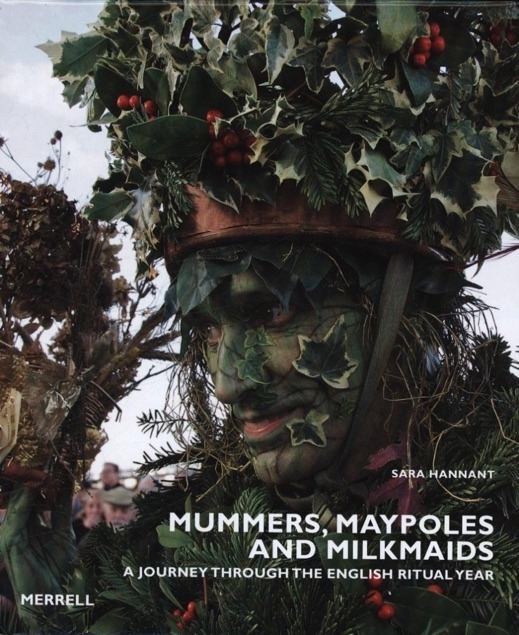

The festival involves a lot of what her husband calls ‘pagan crap’, and he’s right: there are corn dollies and carnival masks and Morris costumes and so much stuff, and I’ll be fair: if you’re unfamiliar it’s all pretty and if my local community put on a party like this I’d definitely go, and if that’s all you want from a movie then you’ll probably be fine with Lord of Misrule, and also I’m impressed you’re still reading this far in to the review so I tip my hat to you. And a nice set of costumes and props don’t prove that this movie is going to be all jingle and no stick.

If anything there’s some acute costuming decisions: this is a contemporary movie and any contemporary English village doing this kind of quasi-Pagan harvest festival stuff is going to have a strong element of revivalism to it.

When we celebrate the ‘joyous old gods’ today we aren’t carrying on an unbroken tradition: we’re reconstructing. Paganism is a new religion, not an old one, and the costumes we see around the village do have the geek-chic, slightly punky quality you’ll see in real modern Morris dance groups.

Likewise, the corn figures and dangling stones and everything else Berrow strews around do look like something a folksy craft group might teach you how to make. Whoever designed this knows what modern ‘pagan crap’ looks like.

I’ll be coming back to that point.

As you could foresee, angel Grace disappears into the woods on festival night. Becca sees her in dream sequences that she attributes to God, the local weird guy Jocelyn Abney (folk horror stalwart Ralph Ineson, who could have done more with a better script) attributes it to the Spirit Gallowgog, and Becca wanders around failing to find her.

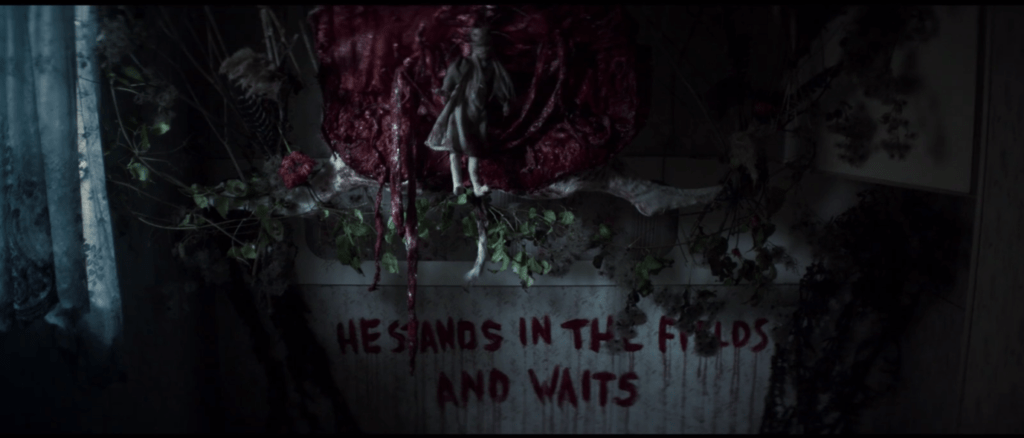

Locals talk a lot about how the Spirit Gallowgog ‘Stands in the fields and waits’, and that makes oddly little sense visually because almost never see the fields. Mostly we see a lot of house porn: half-timbering and exposed brickwork is present in abundance and a lot of different houses in the village seem to have the same nice shade of green paint on their walls, and occasionally we see some spooky things happening in the woods – woods apparently being a required setting in folk horror – but the fields? Barely there.

And they aren’t important narratively either. These aren’t agricultural fields that the village depends on for its livelihood: there’s no sense that this is a farming community. Neither are they geographical fields that isolate you – something that spending time in the countryside definitely teaches you, because fields are big and uneven and you’re not allowed to cross them and damage the crops, and getting past them takes a long time. We don’t see the celebrated harvest come in: people weave little corn figurines, but as far as we can tell they might as well have ordered the corn stalks from Ebay.

This is not a film of fields. It’s a film of cottages and costumes.

It happens over a small, inhabited space – which would be fine if it delved into the closely-jostled personalities of a small community, but really we barely get to know anyone. There’s a brief interlude where an elderly woman has a terrible vision and her middle-aged daughter looks worried about it, but neither their personalities nor their position in the village have anything to do with it. It’s just more set-piece warnings about Gallowgog.

There’s a mysterious family called the Nashes who are suspected of kidnapping Grace, but we see very little of them except that they’re mysterious – a ‘funny breed’ according to the village, but what they count as ‘funny’ remains unexplored, as does ‘breed’. The only other character of significance is Bryony (Alexa Goodall), little friend of the vanished Grace, who sticks around long enough to drop hints that Grace has been taken away, reappears to refuse to tell Becca what’s happened, and then, on being slapped, obligingly takes her down to the Room of Secrets where they keep all the exposition.

It’s a regrettable thing where a vicar slapping a child in the face is the most effective investigative method in the entire film, but that’s how it goes in Lord of Misrule: you save children with child abuse. And where in The Wicker Man we’re free to think Sergeant Howie is being a dogmatical bully when he calls a roomful of evasive schoolgirls ‘despicable little liars’, we really don’t get any judgement of Becca for hitting a child. It just achieves its end, which is not to develop her character or her relationship with the people around her, but to get us to the next set of revelatory props.

Becca’s personality isn’t a factor here: she’s the heroine because the camera follows her around and she has nicer hair than anyone else on screen, and trying to find her daughter never rises above or sinks below what you’d expect of any parent. The Wicker Man’s Sergeant Howie is her obvious fictional godfather, but he’s Christian in a way that adds drama, making him narrow-minded and rude but also principled and courageous, and also, most dangerously, predictable. But Becca is neither inspiring saint nor complicated sinner; her function isn’t to wrestle with her faith but just to shake exposition out of whatever human jar contains the next bit of the plot. So if she hits a child, it’s a morally neutral act.

And on the subject of being a good person, let’s talk about faith.

It should be a significant choice that Becca is a vicar, right? But it oddly isn’t. She’ll kneel down and pray every now and again, and she wears a crucifix – and the prayers really seem about as much a part of her as the bit of jewellery. Christianity doesn’t shape her values, check her actions, lead or mislead her judgement, or do anything else significant.

Even when she reaches out to connect with a parishioner, the best appeal she can manage is, ‘We drank your shitty beer and laughed at your shittier jokes, but it was okay because every week you put a tenner on the collection plate,’ and I’m no churchwoman but I’m pretty sure that’s not the attitude of a good shepherd. ‘We came here to be with God,’ she tells her husband at once point, and we have no idea why she thought they’d find God in Berrow rather than wherever else they came from.

And this is important at the end.

Here’s something important to know about folk horror:

Folk traditions are echoes, but they aren’t institutions. Not unless people make them so.

Consider the Unholy Trinity. Witchfinder General and The Blood On Satan’s Claw do something very convenient for a story about superstitious people: they set themselves in superstitious times. They’re both historical films: witchcraft and demonology are entirely real to the characters, so the fact that they’re fiction to the audience is neither here nor there. The Wicker Man is the odd wicker-man out because it has a contemporary setting – and here’s something that a lot of people forget about it: the Summerislanders’ paganism is relatively new.

Paganism is, as faiths go, younger than it sounds. It’s not even a single religion: it’s a spectrum of faiths that vary from the quite organised to the entirely individual, and it’s too complicated to do justice here, so let’s just say that it involves a lot of human creativity in modern times. These are syncretic belief systems largely developed in the Victorian era with roots in Romanticism – and this isn’t a criticism, it’s just a fact. Now we have a bunch of thriving religious communities with their own established and emerging traditions, and their diligent practitioners are aware that their worship lies in reconstruction and reimagining more than direct continuation of ancient custom, and that’s absolutely fine. Nothing wrong with that. Some wonderful people are drawing some genuine inspiration from these new creations.

But if you’re going to present a demonic spirit in folk horror, you need to decide what you’re going to do about this, because if you pretend this is a custom that’s been going on since ancient times and you can’t find a really good cultural, familial or geographical explanation, then it’s going to ring false. That’s just not how things work, and however fun it is to pretend otherwise, at the back of our minds we know that.

So in The Wicker Man, Lord Summerisle is quite plain with Sergeant Howie that Summerisle paganism was created by his grandfather ‘with typical mid-Victorian zeal’, figuring he’d get a more energetic workforce if he got them worshipping the apples they had to harvest. Once it got started it gathered its own momentum, as religions do, and two generations down you’re looking at true believers – but the fact that it’s a social convenience that both unites the community and preserves the class divisions is vitally present in every scene.

Lord of Misrule spent fifty of Father Time’s whole home-grown organic minutes worrying me that it was going to pretend this was just an inexplicably unbroken tradition before it finally put me out of my misery and explained that no, this was a revivalist faith too.

Give it credit: it pulls off the fairly neat trick of saying that back in the day this was a real vision, it got stamped out by the church, and the ‘old families’ have brought it back fairly recently. As a way of both eating and having its cake, that deserves some respect.

But who are the ‘old families’? We don’t get a sense of that. Why did they bring it back? We don’t get a sense of that either. ‘Heritage thing,’ someone says off-handedly, and if the film thinks that’s reason enough we’re just going to have to disagree. The pagan sacrifice is supposed to bring ‘blessings’, but what do the Berrovians think those blessings involve? This film is an hour and forty minutes long; there is time to explore those questions. But the paganism is as thin as Becca’s Christianity: people just say they believe it every now and again, and it doesn’t shape the texture of their lives. It surrounds them with trinkets, but it doesn’t change their habits, their aspirations, their selves. It’s just kind of there.

And again, folk horror doesn’t have to give a full explanation of any cult it uses. Ben Wheatley’s Kill List (2011) is another descendent of The Wicker Man, and it presents us with only glimpses of what’s going on, religiously speaking – and it works very well. But it works because in that story we don’t need to understand the details: it’s about what it’s like to be on the receiving end of a cultic conspiracy, and what it’s like is confusing. Lord of Misrule requires us to understand the lore for every part of the plot – but of the two, it honestly feels like Kill List that could give you more backstory if pressed.

And Lord of Misrule’s need for lore is serious. There’s a sort of faith-flip twist at the end and it might have been an interesting take on the genre if the different faiths had had heft. Becca reaches a state of reconciliation, let’s say, and there are things you could do with that. You could explore how revivalist Paganism has always been good at incorporating what works.,you could explore how Christianity has a long history of sacramentalising pagan traditions.

You could even do an exploration of how sometimes there’s a kind of Christian martyrdom to be found in renouncing or compromising your Christianity to save others; Scorsese’s Silence (2016) is the masterwork there, but there’s room in the world for more thoughts on the subject. If we’d been soaking in the mythology instead of just having a few mythic soap bubbles drift in front of our eyes, and if that mythology had touched the echoes in our own minds . . . But this doesn’t have any real feel of either Christianity or Paganism here: they’re just a question of whether you wear a crucifix or keep a corn dolly.

And on the subject of material goods . . . this is where I’m going to sink into a deep, dark, uncomfortable secret at the heart of folk horror, the demon whose face we really don’t want to see.

Deep down, so much of folk horror is about money.

Or, more broadly, about what we own.

You know how you know you’re not aristocracy, but folk? You can’t afford to lose much before it breaks you.

Fields and furrows matter when your livelihood means you have to spend all day out ploughing them. Witchfinding is a profitable job when you can charge for it. Summerislanders worship their ‘joyous old gods’ because that’s the basis of their economy. Or to take some good modern examples: Kill List is very much about what you can pay for if you’re rich, and what you have to do for money if you’re not. The Witch’s drama turns vitally on how easy it is to starve if your community won’t keep you, and what such prolonged deprivation can do to people.

Saloum is all about a place where war for profit rips lives apart; The Vigil only happens because our hero is too broke to turn down a job; Ringu is a dire warning against monetising the different. Money is a ferociously animating force in these stories – and that’s not in conflict with the folkishness but in concert. Folks can’t afford to be unworldly. Can you?

Folk monsters steal. They may or may not be murderers, but almost by definition they are thieves. They take the lives of unwilling sacrifices to feed their crops, or they cozen money out of believers by frightening them with scapegoats, or they prey on the edges of fracturing communities and pick off the weak. That’s why they’re monsters: they drain us of what we can’t do without.

It doesn’t have to be about literal money, but it has to be about what you need to survive – which is about more than whether someone kills you in the last reel. Religion doesn’t come from nowhere, and while it’s picturesque to pretend otherwise it doesn’t just bloom up out of your native soil in a spontaneous flowering. It was cultivated, or it was transplanted, or both, and there are historical, political, economic and sometimes military reasons why that particular faith took root in that particular spot. However full of grace the religion that blooms, its origins will never be untouched with the earthly.

But Lord of Misrule is a pretty film. Not beautiful. Not impressively ugly. Just . . . pretty. Lots of houses an estate agent would be delighted to have on their books, lots of trinkets you’d be happy to put on your stall at a craft fair. Lots of objects and items it would be nice to own.

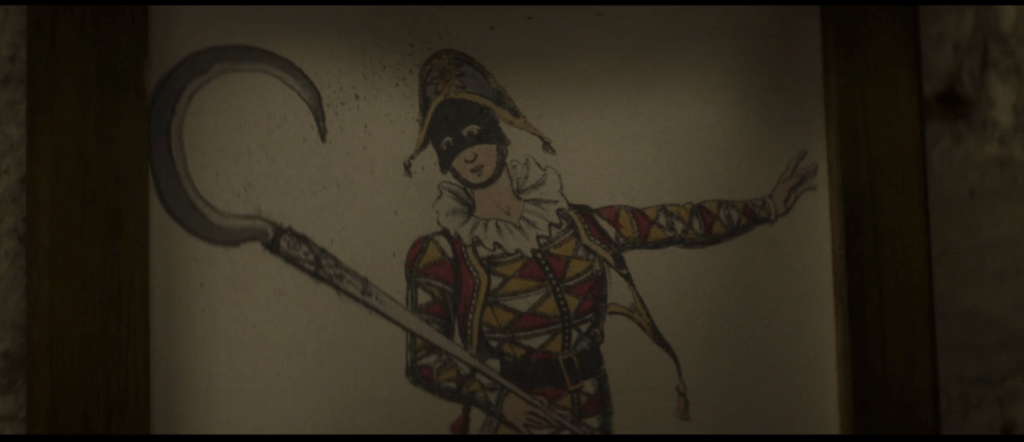

And there’s no real visual cohesion to them: straw gewgaws rub elbows with animal masks, which rub elbows with images from the Commedia dell’arte.

And we’re going to dwell on that last a bit, because I have no idea what Italian bits and bobs are doing in an English pagan community except The Wicker Man rears its head yet again with the presence of a ‘Punch’ costume near the end, and the Commedia dell’arte stuff does look a bit creepy if you’re not used to it.

Okay, I’m sorry, I’m sorry, I can’t help it, I fell down a rabbit-hole on this one. I fell so hard that when I talked about it on Facebook my friend Benjamin Kurt Unsworth called me a nerd – and coming from a fellow fantasy author who I beg for help when I need things translated into Latin, that should tell you just what this movie has done to my brain.

So look. This is the image the Room of Secrets contains of a Commedia dell’arte figure:

Why is it there? I can think of literally no reason except that it’s a call back to Punch in The Wicker Man.

But it’s not Punch. It’s Harlequin – a stock character usually played as a servant in love. Acrobatic, clever, mischievous, fun. That has nothing to do with the Lord of Misrule story.

Petty nitpick? Maybe. But it gets worse! I was doing my best to be fair and make sure I wasn’t hurling false accusations around, and look at this absolute smoking gun I found:

This picture isn’t from the movie. It’s just a picture you can find on Google if you look up the Commedia dell’arte. They lifted it exact and put a sickle in his hand – and not even a whole sickle! They just added a blade to the top of the existing batte, creating a confection far too delicate to last a minute if it was ever used as an actual weapon. That’s Lord of Misrule in a nutshell: take something irrelevant and Photoshop something on top of it, and hope the audience doesn’t know enough to catch you out. Assume no one knows the difference between a theatrical slap-stick and a farming implement, and then bang on about ‘the fields’ without a blush.

Now listen, we’re going to talk worldbuilding, because it may be nerdy but the only way to build a living texture is to keep asking why until you run out of questions. Why, diegetically, is this image here in the Berrow basement?

It can’t be something that comes from the original religious vision in Lord of Misrule, because someone tells us in dialogue that that happened in 1621. This is a portrait of Thomas Ellar, who was an English actor known for playing the role in the early nineteenth century. It’s centuries after the fact.

Would the worshippers have added him later because he fitted the myth? He doesn’t. Thackeray praised the ‘magic wand of spangled Harlequin’ he wielded: it was not a dark part.

But they wouldn’t add him just at random either! Sure, modern eclectic pagans putting together a visual rag-bag of stuff they liked might include it – they could include anything they fancied – but this isn’t that story. They’re supposed to be reviving an actual mythic tradition with real magic power. You’d no more throw in a random bit of décor than you’d put a Buddha statue on your church altar. This isn’t a mood board, it’s a religion.

Except it’s not, because this is fiction and if it doesn’t hold together then it just doesn’t. All it does is send people like me into a research frenzy. But in the end all I’ve got is that it’s there because this is a movie full of objects there to look nice, not to communicate story. It kind of is a mood board.

I talked about about Adam Scovell’s ‘folk horror chain’ back in this essay – way, way back – and let’s talk about it properly now. Scovell proposed a working definition of folk horror that required a specific chain of events; his aim was to create a ‘litmus test’ that allowed fans to build a canon that embraced more than English folklore. An admirable goal.

Now, I would never reject a work for being Not Folk Horror if it deviated from this definition but still plucked my strings; why miss out on something great just because it’s a little unusual? But there’s nothing unusual about Lord of Misrule: its whole problem is that it’s trying to be folk horror by copying other folk horror. When a film’s whole plot is dictated by trying to fit a template, asking whether it actually fits is fair game.

So what is the ‘folk horror chain’? Scovell’s definition calls for the following sequence of cause and effect: there is a particular landscape, it isolates the community, the isolation leads to ‘skewed morality and belief systems’, and these in turn climax in some kind of ‘manifestation’, a supernatural or violent expression of the danger within.

Lord of Misrule isn’t a chain. It’s a set of broken links. It ends in a summoning all right, but how does it get there?

Berrow’s vaunted ‘fields’ are hardly visible; its landscape is mostly indoors, and nothing is done with the interiors either.

Is it isolated? No more than any other English village, which in this day and age is not very isolated at all. Berrow has phones and Internet just like anywhere else. Even its costumes are typical rather than weird, and there’s no reason to assume you couldn’t just get in your car and drive ten minutes to the next village over.

Do they have a skewed system of belief? What they believe is so extremely vague that any tick in that box is the faintest of pencil.

So when we have the ‘manifestation’ ending? There are no links in the chain leading up to it.

A single chain-link is just a bit of scrap with nothing at its centre.

Like I say, genre snobbery is a waste of everyone’s time. But there’s nothing to Lord of Misrule except the genre it’s trying to do, and it doesn’t do it. The story has events in it, and if they were built up to and built on, they’d be satisfying beats. But they weren’t, so they aren’t.

There are genres where if you can do a good job on the more mechanical aspects you can get away with a slight or formulaic story; you might not have made a masterpiece, but you haven’t wasted the audience’s time. Give a slasher good kills and it doesn’t matter if you’re not Psycho (1960) or The Texas Chainsaw Massacre (1974). Fill a house with spooky ghosts and put in some decent jump-scares and it doesn’t matter if you’re not The Haunting (1963) or The Others (2001).

Make a torture-porn audience squirm in their seats and it doesn’t matter if you’re not Martyrs (2008). But folk horror isn’t one of those genres: if it’s flexible and inclusive, it’s also unforgiving. Folk horror depends on theme, and theme can’t be scamped. There are shallow ways to make an audience flinch; there is no shallow way to make an audience feel a haunted ambivalence about their relationship with the collective subconscious. If you tell a story about a neo-pagan village with a human sacrifice ending and you’re not The Wicker Man . . . then Senator, you are not The Wicker Man.

I’m being unkind. I’m sorry. I got provoked, because a film that depends on you not to know any better is a bugbear of mine. More charitably you could say it watches like a first draft that should have had several more rewrites to flesh out the characters so their final decisions make sense: some people do write the beats first and the justifications later. And the film’s ending, given more heart in the rest of the story, had the potential to be uplifting and life-affirming.

It’s just that this stuff needs to feel like it’s happening to real people. What’s happening is never, on its own, enough to pack the punch. The ending of The Wicker Man didn’t scar cinema just because it’s shocking to burn a man alive: it’s shocking that this man would burn that man alive. Christopher Lee’s Lord Summerisle is urbane, amusing, carrying his faith with a light self-mockery that makes it hard to believe it could ever turn deadly serious. Edward Woodward’s Sergeant Howie is hard to like, but he’s impossible not to respect: he’s resolute, dauntless, so inflexible and implacable that he seems indestructible.

That this charming gentleman would calmly, happily torture to death this ferocious force of righteousness – you can hardly believe what you’re seeing. And yet you have to, because you’ve seen the personality of the whole community. This is horror when it comes alive.

I’m sorry to beat on Lord of Misrule; there’s been a number of post-2010 folk horror movies that are more style than substance and it’s probably not fair to take out all my frustration on this one movie. It’s more constructive instead to take it as a case study: if you’re doing deliberate folk horror, this is one way you can go wrong.

Folk horror can look very pretty. That’s one reason to love it. Folk art is a treasure trove and folk landscapes speak to something deep in us, and the whole genre is saturated in a kind of hiraeth spiced with the fear that makes it really mean something.

Home isn’t home unless it’s bigger than us, and one way to know something’s bigger than us is to show it could swallow us alive.

But you can’t start with the prettiness.

The horror has to have a coherent mythology. That mythology has to be interwoven with a particular culture. And that culture’s artifacts need to look as if they come from that culture: from one particular culture with its own artisanal and artistic traditions that carry a distinctive feel that can tell you at a glance, ‘Yes, these things come from here.’

And ‘here’ needs to be a place of people, who need things and feel things and exist in their own right, not just as a backdrop for an outsider to wander around. We know human sacrifice is a pagan tradition in fiction; The Wicker Man was surprising fifty years ago, but come on: that was long enough for someone to have literal grandchildren, and it’s not exactly an obscure movie. It pops up on ‘best scary movie’ lists all the time even if you aren’t into folk horror, and films that watch as if they think nobody else has seen it are not going to work on the audience most likely to watch them in the first place. We need a reason for any of this.

So by way of a positive example I’ll refer back to Jug Face, which I mentioned near the beginning of this review. It’s not on Shudder, but it is on Amazon Prime at the time of writing, and while it’s not perfect it is seriously worth a watch.

The premise does the same thing a lot of bad folk horror movies do: it uses human sacrifice as a plot point. But it does it smart.

Jug Face knows that we’ve all heard of The Wicker Man and Children of the Corn, so it doesn’t fool around waiting for an outsider to figure out what we can see from a country mile away. It begins with a credit sequence of childish drawings telling you the entire story of how human sacrifice came to this scrap of American backwoods: there’s a small muddy pit in the forest that somehow sends out visions to a chosen person, who sculpts a clay jug bearing the face of whoever the Pit wants sacrificed to it – and if the Pit doesn’t get that person’s lifeblood, something comes out and goes hunting.

Back in the day there was an epidemic, and the local priest wasn’t able to do anything about it, so when the Pit demanded his blood they sacrificed him and the Pit cured them all, so of course after that they worshipped it. And now it’s modern times and they still do because they’re dirt-poor and can’t afford any other kind of healthcare, and also because once you’ve sacrificed people you love to the Pit, and they’ve gone with the quiet grace of martyrs, how could you bear to believe they died for an evil cause? So today they’re a religious community of demon-worshippers who genuinely act like a small Christian church about it because when this is your normal, that’s what you do.

Jug Face, getting straight to the point. Look how much information it packs into a single image.

Human sacrifice is a thing that happens in folk horror.

Jug Face knows you know. So it puts the guessable part right there at the start, and then gets on with telling a story about what it’s like to live under that kind of religion. And it gives a very clear and believable reason for why things got that way and haven’t changed. And from there . . . it has something real to say.

Jug Face is the story of a young woman called Ada (Lauren Ashley Carter) who finds herself marked for sacrifice, but unlike the rest of her community she just can’t resign herself to it: she doesn’t want to die for the Pit, and she can’t really explain why because nothing in her life has given her the vocabulary to justify it. We can see it’s because she’s a kinder person than the rest of her clan: she’s a sinner all right, but she’s never been able to resign herself to cruelty even when it would make her life easier, so the misery of the Pit stands out starker to her than to everyone else who’s had to harden their hearts or shut down their minds. But she can’t say any of that, so all she can do is try to escape.

Ada gets very little say in her own life.

The potter-prophet Dawai (Sean Bridgers) wants to help her in this – he isn’t a bloodthirsty believer, he just gets the visions because the Pit has picked him for unknown reasons and he sculpts in an involuntary trance – but he’s up against an impossible problem because, potter or not, he doesn’t have any power in the community. He has some kind of learning disability and the others don’t even give him the grace of thinking him a holy fool. As far as they’re concerned he’s just a ‘fool’, and Ada’s mother doesn’t want Ada to be friends with him because if they hook up and Ada gets pregnant (which is not on the cards), it would produce more ‘fools’ as children.

But director Chad Crawford Kinkle has a sister with Down Syndrome who he evidently loves – he cast her in his next film Dementer (2019) – and Jug Face has something important to say about this genre of story where ‘hillbilly village idiot’ is a common and ugly trope. To wit: cognitively impaired is not the same as stupid.

Jug Face. Dawai (Sean Bridgers) in his workshop being his usual practical, kindly self. Check out the distinctive style of his sculptures: the film bothers to create visual originality.

Dawai is the sanest person in his whole church.

He has a slow processing speed and it takes a few extra instants for his thoughts to go through the works, but when he gets to the thought he wanted, it’s always the right one. His speech is a bit awkward, but his observations are perceptive. Dawai’s ideas are commonsensical and founded in compassion, and he doesn’t have the rationalising skills to talk himself into bullshit. And if he thinks something is the right thing to do, then whatever it costs him, he can’t find any reason not to do it.

If you value normality it’s easy to overlook the fact that Dawai is a hero. But if you value normality . . . well, around here it’s normal to cut throats over a demon-plagued pit. So maybe, Jug Face lays out for our consideration, there are things in this world more important than being ‘normal’. Maybe people are precious in and of themselves.

See? A folk horror film with human sacrifice that actually has something to say. It’s not pretty because it’s too busy saying something fucking beautiful.

(Excuse me. Again, if you see your heart up on screen it’s hard to be temperate.)

Lord of Misrule is a film of bijou cottages and cute little knickknacks. You could keep it on your shelf – but when it comes to having something to say? Honestly, the most it seems to have to offer is that a mother should live only for her child. ‘Spirit Gallowgog made a home for your daughter when you didn’t,’ Becca is told, and exactly what she did that failed to make a home for Grace other than have a job and expect her husband to do some babysitting is anybody’s guess. A

dd that to the fact that it’s a film where we’re encouraged to judge a father harshly for the crime of accepting his child’s death, and it adds up to a film with no heart. People have social roles they’re supposed to fulfil, like ornaments have spots on a mantelpiece, and that’s all that counts. It has nice living-rooms in it and no real people living in them.

Why do we have folk tales? Because we’re folks. People need to tell stories to show each other what can’t just be told. We need this. We want this.

But a story should be about a need, not a want.

Folklore is free, but folk horror is a commodity. Heck, it’s a commodity I’ll pay for, and if I can’t get enough of it I’ll make some myself. (Again, go buy my books; we live under capitalism and I have to shake the tin for sales like everybody else. They feature both folk monsters and the fact that sometimes ‘I can’t afford to protect the people who need it’ is a horror of its own.) We need some of that joyous old fear; it lets us feel the soil beneath our feet. But it’s those who use that need we really should be afraid of: the witchfinders and the lords of the apples who know our pagan hearts and tells us that safety or joy can be had for a price. We need to be reminded of where real value lies.

And if a film is made up mostly of props you could buy at a souvenir shop – well, any film is a commodity, but that’s a film that’s only a commodity.

We invent tales. Sometimes we invent whole faiths. That’s all right; that’s how we fit ourselves into an impossibly vast world. But if you just slap in any old this and that because it looks pretty, and don’t ask yourself the whys and hows that lie in human hearts and human histories, then pretty is all you’re going to get.

And it doesn’t have to be like that. We’ve seen The Wicker Man; we don’t need another one, even with a twist of lemon at the end. Folk horror has no rules; nobody created the genre on purpose and nobody is in charge of it, and nobody can stop you doing whatever you think would be marvellous. It’s not about the props, it’s about the ways of being human people in groups create for themselves, and the lives they have to live within that. You can do so many amazing things with that, and I don’t see why we should settle for less.

Because amazing things can still be done. They’ve even been done this year. That’s right: this folk horror kick is a two-parter, because next time I’ll be talking about The Devil’s Bath. It has a beautiful rural aesthetic; it tackles themes of faith and death and sacrifice; it has an ending that feels like a direct reply to The Wicker Man. It even has a flower crown at one point.

And it gripped me by the very soul.

In the Heart of Hidden Things (The Gyrford series) by Kit Whitfield

Jedediah’s father walked out of his life forty years ago. Now he’s back. He won’t apologise, he doesn’t explain – and, impossibly, he hasn’t aged a day.

If you asked the folks of Gyrford, they’d tell you Jedediah Smith looked up to his father. After all, Corbie Mackem was the Sarsen Shepherd: the man who saved the Smith clan from Ab, the terrifyingly well-meaning fey who blighted a whole generation with unwanted gifts.

Corbie was a good fairy-smith. And if he wasn’t a good father, well, that isn’t something Jedediah likes to talk about. Especially since no one knows where Corbie’s body lies: the day of his son’s wedding, forty-odd years ago, he set off to travel and was never seen again.

These days Jedediah is a respectable elder, more concerned with his wayward grandson John than with his long-buried past, and he has other problems on his mind. There’s the preparations for Saint Clement’s Day, and the odd fact that birds all over the county have taken to hiding themselves, and the misbehaviour of Left-Lop the pig – which has grown vegetation all over its back, escaped its farm and taken to making personal remarks at folks in alarmingly alliterative verse.

But then disaster strikes. Ab is back. And Corbie, thought long dead, returns to Gyrford – younger than his son . . .