Faerie Tale by Raymond E. Feist – A My life in Horror

There was a particular book when I was very, very young, a book that sat high up on my Mother’s bookshelves in the living room. I can’t recall precisely when its cover snared my attention; only that I was too young to clearly apprehend it, certainly too young to read the story it illustrated.

As adherents of these articles know all too well by now, I’m perpetually fascinated by images that sear themselves into our imaginations. Most that come to inform the shape and nature of that phenomena occur during our formative years, when our minds are open, receptive, pliant. They pour into us, infect us in a strange way, then become symbiotic; living parts of who we are.

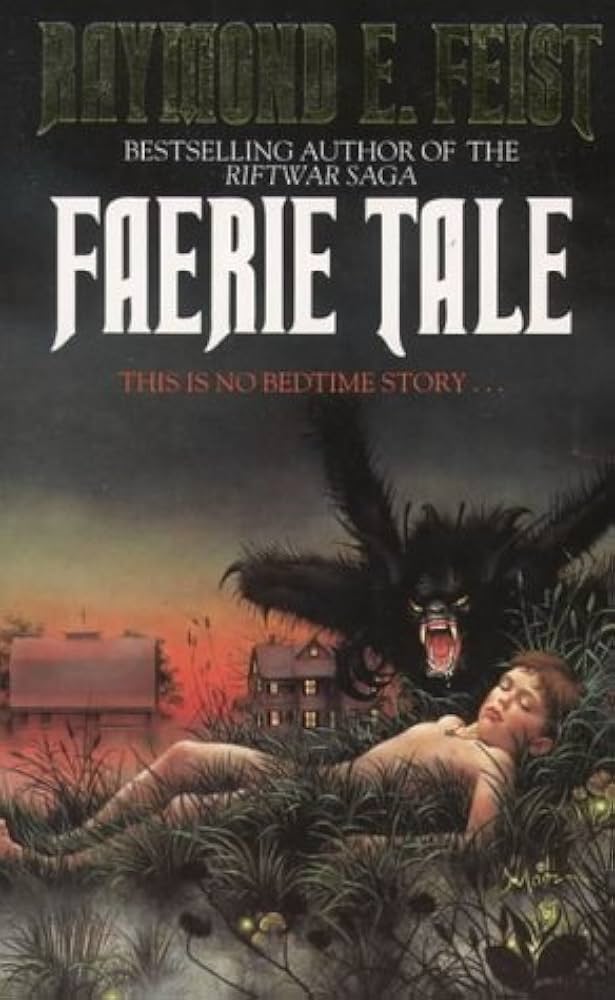

This book, this particular edition, is one of those images:

A dusty, tattered hardback, it sits amongst others: An immense copy of Stephen King’s IT, cover depicting a house nightmarishly distorting into a clown’s face, a copy of The Stand by the same author, cover dark and tempestuous with lightning. This book is different from those it sits amongst: More fantastical, more fey, but no less distressing:

In dank grasses beneath a dusky sky, a naked boy lies, perhaps asleep, perhaps otherwise. In the distance is a house, from which he might have strayed or been stolen by powers we have no notion of.

Lowering over him is an obscene thing; a creature of spidery limbs, a black, bulbous body, a goblinoid face, distorted into a hateful scowl. That it has intention to harm the sleeping boy is beyond doubt; the thing is rendered as an uncanny, mythic evil, designed to provoke terror and repulsion. The expression on its warped face is nightmarish, simultaneously alien in its hatred yet wholly familiar.

Whilst I was too young to consciously appreciate such details when I was a boy, the juxtaposition of the sleeping child -vulnerable, angelic in the grass- and the obscene monstrosity communicates the thematic extremes of the book’s subject perfectly:

It would be many, many years before I was allowed to read the book for myself.

Despite already having a fair pedigree in mythology and monsters -everything from Nordic to Ancient Greek, from Hindu to the folklore of what we fallaciously categorise as the “Celtic” peoples-, my Mother was reluctant to let me read this one until I was a little older. In that, the book retained a certain mystery for many years: I could only conjecture as to what lay between its pages, what the ghastly entity adorning its cover was and wanted.

For a time, the book disappeared, spirited away into the loft or some other storage space. During that period, I became acquainted with the work of Fantasists such as Tolkien and Lewis, Peake and Le Guin, as well as horror writers such as King, Campbell and Barker.

When the book reappeared, likely during some routine cleansing of the loft, it precipitated a flood of nostalgia: I recalled how enthralled I was with the cover-image as a young boy, the rampant imaginings and dark day dreams it precipitated.

Now, I was more than ready to explore the book for myself (and unlikely to be gainsaid in the adventure).

I recall devouring the book over the course of a week during a school Summer holiday. When most children of my age were out finding adventure in the sunshine, I was sealed away in my room and my own head, wandering spaces of a more fraught and abstract kind.

Thematically, Feist’s Faerie Tale echoes later works by the likes of Clive Barker: As in that author’s Books of the Art, this is a work of distinctly US, colonial mythology; a commentary on how certain myths and meta-narratives accompany us, haunt us and our descendants, no matter how far we stray or remove ourselves from our ancestry. In Feist’s case, the stories in question are those still well known in certain parts of Ireland, Wales and traditional cultures in the UK (not to mention across the European continent):

The eponymous Faeries are not the glowing, friendly sprites we might recognise from Disney films or cartoon TV specials. Rather, they are the fey and ambiguous denizens of lost and forgotten spaces; children of nature, and as complex and ambiguous as the wild lands they inhabit.

Feist takes special care in his writing not to moralise these creatures one way or the other:

They are beautiful, enchanting, sensual and pleasurable to be in the company of. They are also capricious, mercurial, infantile and spiteful, taking as much delight in screams as laughter.

By transplanting them into the forgotten woodlands of the US, Feist creates a dichotomy between the post-modernity, rationalism and materialism of 1980s US culture and the world of abstract imagination, of dreams and subconscious drives, old-world supernaturalism and superstition. Pushed to the very borders of waking reality by not only human expansion, but human rationality, they now operate in lonely, shadowed areas; liminal spaces that only children can perceive or comprehend.

Thrown into this potentially volatile situation is the Hastings family and their friends: A rag-tag band of academics, imaginers, poets and mystics who arouse and attract the fey creatures living in the woods at the borders of their newly purchased property. In particular, the Hastings children, Gabbie and her twin brothers, Sean and Patrick, become the foci of the strange phenomena and even stranger entities that occur as a result. The two boys, being of a pre-pubescent age where the world is still unfixed and the distinction between reality and imagination has yet to become definite, draw the attentions of entities both benign and exceedingly dark, struggling to communicate to their rationalist parents what they’ve experienced first-hand (until they have no choice but to believe).

It’s here that we begin to learn the nature of the beast adorning the front cover: This is Feist’s rendition of a classic Fey entity; one that’s existed in various forms in folklore and faerie tales since time immemorial:

A Changeling.

Already being well familiar with the folklore and oral traditions Feist draws from, I was simultaneously excited and horrified by this revelation: In most tales, The Changeling is a dark creature, snatching away children for its own vile purposes and shifting into their shapes, taking their places in the household. Many have theorised that Changeling stories are most likely pre-history ways of attempting to process and rationalise certain phenomena that peoples of earlier, less rational eras lacked the means to understand: A child suffering from mental illness, neurological disorders or shifts in personality as a result of infections or trauma, for example, might have begun to behave in wild and erratic ways; ways that must’ve seemed demonic or otherworldly to those who knew no better.

In Feist’s Faerie Tale, The Changeling is an avatar of all those dark tensions;

A living manifestation of alienated, misunderstood childhood, pain and trauma. It is the monster most parents fear in their children, comprised only of sadism, spite and envy. There’s a wonderful, mythological purity to the creature, as there is to most of the Fey things we encounter. Whilst its is a dark purity, there’s something nevertheless fascinating in what it metaphorically reflects:

It is both attracted to and repulsed by Sean and Patrick, in whom it sees reflected a condition it can poorly emulate but never have. It wants them with a monstrous urgency that’s disturbing in itself, but is also bound by certain mythological rules it cannot break.

As such, it is a frustrated, servile, self-loathing creature; a mass of utter negativity that hounds the family throughout the book, inflicting escalating -but universally mean, spiteful- cruelties on them, until it finally fulfils its mythological archetype; taking the place of one of the boys, who is spirited away to the realm of the Faeries themselves.

In this guise, The Changeling is arguably at its most subversive, monstrous but also its most classical: This is the Changeling of myth and folklore transplanted into the world of psychological and materialist realism, in which the violent, wild and grotesquely sexual behaviours suddenly exhibited by one of the boys is deemed a matter of disturbance rather than magic, an affliction of the mind rather than the soul. It’s arguably the most distressing part of the book reading of the family attempting to cope with and rationalise these phenomena whilst knowing, with a reader’s benefit, that the creature they’re attempting to understand is not their child, but a literal cuckoo in the nest.

Meanwhile, other Fey entities exhibit their own influences and qualities:

Those attracted by Gabbie, for example, a young woman experiencing her first forays into love and sexuality, reflect those experiences: From the Puckish, Pan-like entity who seems to be youthful lust and vitality made manifest to the more paternal smith whose influence is of a darker, more Elektra-Complex nature. The Faeries and their world are consistently portrayed -albeit subtextually- not as apart from humanity, but as reflections of it.

Perhaps the most complex in this regard is the book’s antagonist,

Lord of the Wild Hunt, King of the Fey, The Erl King. A creature of so many aspects and faces, he shifts from one to the other between blinks. A rapine and sadistic individual, yet also inspired, beautiful and profound. Like all of his court, he is a force of nature, but nature at its darkest and most perilous.

He is bleak masculinity, appetite and the will to dominate made manifest, to which innocence is anathema, almost blasphemous in nature. We learn at one point that the hideous Changeling is an expression of this quality; an inversion of the classic myth in that it originally was a child of this world, taken by the Erl King, twisted and transformed by the dubious pleasures of his court into the shape it now bears. It is a hideous reflection of a possible future for the Hastings boys; one in which all parameter has been torn away, all definition undone, leaving only raw appetite and desire.

Originally, I recall being struck by the marriage of domestic reality to the mythic. Faerie Tale must have been one of the first books I read that exhibited this quality (one that would come to obsess me in the years to come, reflected powerfully on my own writing). Alongside the likes of Clive Barker’s Weaveworld, it served to expand my tastes beyond the more traditional fantasy of Tolkien, Lewis et al, into more fraught and ambiguous territories.

Coming back to Faerie Tale for the first time in well over a decade,

I was struck by how of its era it is; a portal back into the styles, tropes and concerns of not only 1980s Fantasy writing, but Horror too:

There are sequences here more redolent of King and Barker than Lewis or Tolkien. The eponymous Fairies are not primary-coloured Disney creations, all cuteness and comedy antics: They are deep and resonant manifestations of the most ancient folklore, tales whose ambiguity and amorality is akin to that of a flood or hurricane: The emotions they excite in human characters ranges from sublime and terrifying sexual arousal to exquisite fear, unutterable despair. At various intervals, otherwise composed characters are reduced to terrified children, the elemental forces at play having an effect not only on human psychology, but reality at large.

Feist paints a world in which conditions collide: 1980s, rural Americana, in all of its materialism, crassness, lack of poetry, seemingly invaded by realms of darker, more ancient provenance: States of pure poetry in which modern concerns -not to mention moral constraints- are revealed as picayune and petulant.

The ambiguity of these forces is one of Faerie Tale’s greatest strengths:

Even as a child, I was always more interested in the monsters than the heroes. Here, even those entities that appear as elementally negative are also essential parts of metaphysical reality, no more worthy of dismissal or condemnation than frost in Winter or a Summer drought. They are also explicitly seasonal in nature: Entities that appear initially sympathetic or helpful reveal troubling, even fearful ambiguities, and vice versa. What “evil” exists here is not entirely otherworldly, rather abstract and metaphorical. The excesses of the Faeries, which range through a spectrum of identifiably human cruelties, are redolent of certain powerful drives and conditions within humanity, taken to the extremes that only beings unbound by need or time can.

They are seductive and magical and powerful beings, resonantly sensual, sexual and unconcerned by consequence. This also makes them extremely fey, dangerous and unpredictable, especially in the presence of children and the human youths they take especial interest in.

The ambiguity of its fantastical elements of Faerie Tale is something I’d rarely encountered before upon my original reading; whilst the traditions and folklore upon which they’re based are resonant with that quality (the horrific tales of fey creatures deriving from old Irish and Germanic folklore are particularly notable), there was a noted tendency for Fantasy of the era to be more morally absolute, more black and white. Here, the forces at play don’t conform to easy or comfortable archetypes. Even those that appear with benign intentions are also threatening in certain notable ways (a sexually-charged encounter with a mythic blacksmith is simultaneously arousing and subtly dreadful, the potential for the encounter to turn sour pervasive).

Another element that chimed profoundly with my own developing fascinations

largely owing to the influences of Blake, Barker and Martin (AKA Brite)- is the marrying of the sexual to the mythological. This is not a new or post-modern element of those stories, rather a return to essential qualities that have been shorn from or suppressed within them by a desire to diminish or commercialise. A casual glance over the stories Feist is drawing on reveals a wealth and depth of dark sexuality; reflections of certain cultural concerns that are simultaneously specific to certain old societies and indelibly, universally human:

During her encounter with the mythic blacksmith, Gabbie Hastings is almost overwhelmed, even subjugated by the aura of raw, male sexuality surrounding him. However, the experience is not one entirely of pleasure: The peak that it brings her to is a form of surrender, she realises, the male entity exercising power over her the like of which she’s never experienced and feels far, far from comfortable with. Interestingly, this also marks a point at which the fey realm seems to echo the emotions and concerns of the human characters that encounter it:

Gabbie is in a state of heightened sexual frustration owing to her burgeoning relationship with a young man named Jack, and it’s this quality that the Faeries reflect back at her. Throughout the story, it seems that certain states of mind and emotion necessarily attract -or even influence the natures of- specific fey entities whose aspects reflect them. Gabbie attracts entities redolent of her state of mind and emotion, as well as her younger siblings.

With regards to Gabbie specifically

this is arguably one of the areas where the book betrays its age, and the cultural contexts in which it was written: A rich, teenage girl, she is markedly irrational at times, often submissive to the paternal figures in her life. The occurrence of her sexual assault by some fey thing is treated more as a darkly erotic dream than something that physically occurred (which, although emblematic of the liminal metaphysics at play, is enormously problematic).

The social status of the family -and most of the principle characters- may pose a problem to readers in the 2020s: These are, after all, rich 1980s materialists, people who are encroaching on a land and culture in which they are strangers. It’s not difficult to see how the dynamics of the story might be subtly shifted were it written today to make them the antagonists (however unwitting) and the Fey things whose realm they partially squat on the victims (even at the time of publication, there were writings in fantasy and horror that evinced exactly that: It’s not difficult to see, for example, how contemporary Clive Barker would’ve had much more sympathy for the Faeries than the human beings they “prey” on).

Gabbie in particular is enormously problematic at times in terms of her presentation:

She is more of an archetype of “teenage girl,” as written by a straight male of the era, than a character in and of herself. Her occasional lapses into jealousy, paranoia and near-hysteria, whilst justified within the text, are also occasionally difficult to reconcile with who and what she presents of herself at other intervals.

There’s also a marked tendency for characters to effectively become text-books when the story requires it: Everyone involved seems to have their own academic speciality just coincidentally tailored to the exact situation, enough so that they can convey theories as to what is happening and why (there’s a particularly notable -and somewhat convenient- section shortly after Gabbie’s assault in which one of the paternalistic, sage-like characters reveals they just so happen to have degrees in therapy and psychiatry, thereby allowing them to proclaim on the subject at length).

One of the most fascinating elements of reading Faerie Tale now is the window it opens into an entirely other world; not merely the mythological condition of Fey things and spirits, but the publishing realm of the 1980s:

Fiction, particularly Fantasy and Horror, was in a very different condition back then.

At the height of the boom period started by Stephen King and continued by Clive Barker et al., it was undoubtedly a time of high invention and incredible output, but also the dominion of certain voices and assumptions. Faerie Tale is an odd beast in that it’s simultaneously a manifestation of and flirtation with those assumptions:

The central characters, whilst their politics is never overtly discussed, are all rich, professional and, for the most part, semi-famous. They are financially and materially secure, able to make a project of establishing their new life in accordance with Reaganite prescriptions of what wholesome, heterosexual, American family life “should” be.

At the time, this would have been largely standard; the kind of characters and status quo one would expect to find in this sort of fiction. From a 2024 perspective, it’s difficult to have unambiguous sympathy for the rich family who blithely turn up in a setting they do not know or sufficiently respect, who effectively treat it like their back yard and playground.

Subtextually, that’s certainly a theme of Faerie Tale

One that’s overshadowed by the veneer of 1980s wholesomeness and veneration of the “family” as a concept. Their “normalcy” -which largely consists of conforming to materialist prescriptions of what a family should be- is presented in contrast to the wild and Fey things their presence arouses, and as a desirable and sacred thing. There is a conservatism inherent to the text’s assumptions that results in a certain moral binarism, which doesn’t necessarily suit the subject matter.

Other Fantasy writers of the era -and certainly in the years following- would use similar subjects to explore elements of the USA’s colonial history (e.g. commenting upon how the mythologies and superstitions of settler demographics have operated as instruments of cultural erasure, coming into conflict with the beliefs and oral traditions of the nation’s native peoples, sometimes cannibalising or incorporating elements thereof, but more often obliterating them entirely).

This is not something that’s even referred to in Faerie Tale,

which, given that it is explicitly about how stories migrate and find niches wherever they’re carried, is a little troubling.

Again, being an example of 1980s genre fiction, its general whiteness, straightness and lack of even reference to anything outside of extremely defined bounds might be difficult for present day readers to swallow. It must be noted, of course, that Feist’s project is very particular and well-researched: An examination of certain types of oral tradition and how they operate when uprooted from their land of origin and translated into a post-modern time and setting. However, the lack of voices within the text other than its very limited range of demographics is curious, and oddly quaint to a queer reader of the present day.

More than anything, the book is an object of sentiment and childhood association: I recall noticing that peculiarly distressing cover when I was very young, and incorporating its imagery into my own nightmares. As an article of fiction? It stands as a window into another time (that may as well be another world): When I say “they don’t make them like this any more,” I mean that sincerely, for good and ill. Revisiting it for the purposes of this article has been a potent nostalgic thrill, and one the child in me has relished, but also a reminder of Tolkien’s most potent lesson:

We can never go home again.